In the first of a series of reports from California, Richard Siddle, first looks at how Lodi is becoming one of the most exciting and important regions in this super competitive stage, with both its focus on sustainability and experimental winemaking.

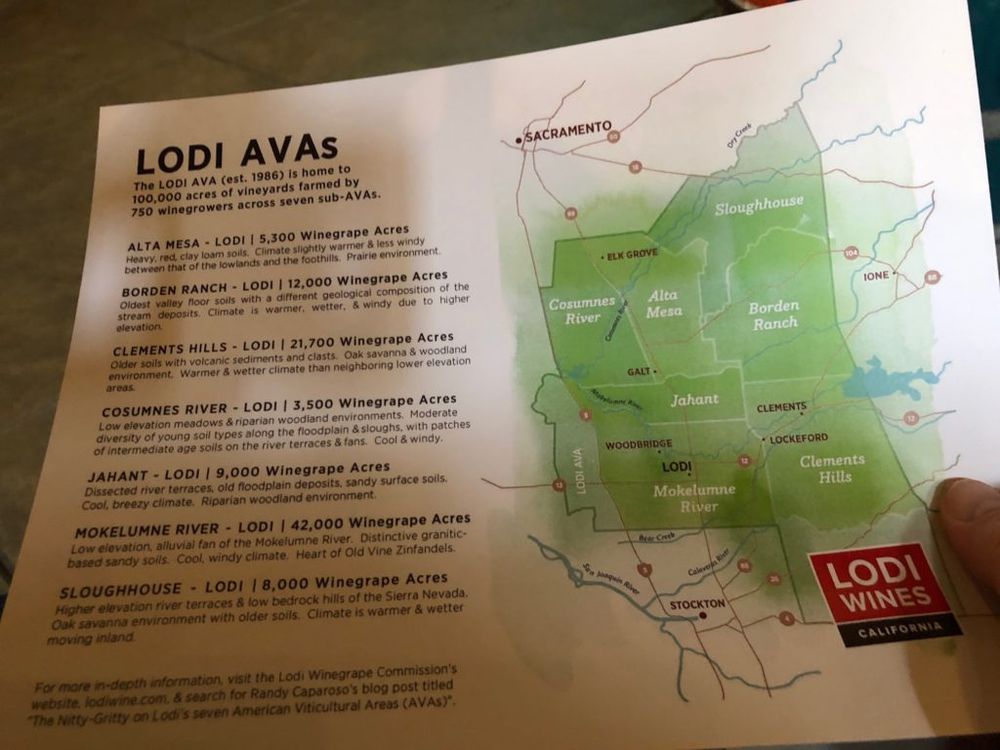

Lodi may not be as famous or as prestigious as Napa and Sonoma, or most of California’s other premium wine producing regions, but it is fast coming up on the rails to be arguably one of the most influential in terms of the wines that California is now capable of producing. Which considering it also happens to be responsible for around 20% of California’s entire grape crush ever year, from its 100,000 acres of vineyards, is good news for the wider US wine industry.

The key to Lodi’s new found success lies in the fact its soils are capable of producing over 100 different grape varieties. When California as a whole boasts of having well over 100 grape varieties in production, the vast majority are in Lodi. Those soils also have the oldest vines of anywhere in the state, dating back to the 1880s to when the first pioneers went west looking for gold in ‘them thar hills’, which just happen to be the Sierra Nevada mountains that provide the backdrop to the Lodi wine region as a whole. Put those soils, old vines, and grape varieties together and you have potentially the most exciting and innovating melting pot for winemakers in California.

Crucially most of the growers in Lodi also have their roots that go back to those pioneering days with fourth and fifth generation families working the same soils as their predecessors, offering invaluable experience and knowledge to the major wine companies that have set up the equivalent of their second homes in the region.

First for sustainability

Lodi’s Stuart Spencer says its sustainability programme has been built for and by the growers

What Lodi can certainly claim for itself is that it was the quickest off the mark to grasp and drive the sustainability agenda that is so important to the Californian region as a whole. Its Lodi Rules programme, which dates back to 2005, is widely seen as the benchmark, or at least the forerunner on which many of California’s other schemes are based.

It was certainly the state’s first third-party certified sustainable wine growing programme and within Lodi itself there are 24,129 cases of certified wine produced each year. Its influence, however, can be seen right across the state with more than 47,000 acres in 13 crush districts in California certified to Lodi Rules and it has been highly instrumental in the setting up of the California-wide Certified Sustainable programme. In Lodi alone 24,000 acres in 2018 were certified sustainable.

Its success, claims Stuart Spencer, executive director of the Lodi Winegrape Commission, comes down to the fact it is very much driven “by growers for growers” and at its heart is about “generational farming” and protecting the land – and the community – for the future.

It goes far beyond what is happening in the vineyard, he adds, but looks at the whole “ecosystem” of the area, from the wildlife, hedgerows, and how it all interacts with each other. It also stretches out to cover social, training and education issues for people within the wine farming community. “We look at how you treat your employees,” he says, as well as how you are looking after your birds and bees.

Unique conditions

It’s also about creating a set of rules and standards that help growers better understand the unique climatic and soil conditions that govern how grapes are grown in Lodi. All of which comes back to the strong delta winds that sweep in from the coast taking hot day time temperatures down to what can be very cold nights, particularly in the western side of the region.

“We are blessed with our climate, it’s such a cool place to be,” says Spencer. “There is a lot more self confidence in the region now. We are not just growers, but making our own brands as well. Our climate and soils not only allow us to plant different varieties, but they also mean we can grow them well and true to where they come from.”

Clay Station, part of Delicato Family Wines, was one of the first producers in the region to be certified under Lodi Rules, back in 2004. “We are improving all the time. We do not have the same approach for all our vines. It is all based on the variety and the soil. We have five immigration systems that we use to ensure we are saving as much water as we can,” says Robert Pirie, Clay Station’s vineyard manager and one of the originators of the Lodi Rules programme.“We look at every field differently. After all if the fruit does not taste good in the field, it won’t taste good in the bottle.”

Clay Station’s Bud Bradley explains how there are big differences within single vineyard plots along with, left, Robert Pirie, and Danny Lucchesi

Bud Bradley, Clay Station’s director of grower relations, agrees: “No two farms are the same. In fact they can change soil types and conditions every 100 feet. It’s a hard place to farm. You need to be really skilled to be good at it.”

It’s why so many of the growers Delicato works with have been supplying wine to the group for 25 years or more. “We like that. We can work with the families over a long period of time so that they know what we want and can do things in the Delicato way,” he says. That’s what makes that grower, producer, winery partnership so strong in Lodi. It has been built up over generations.

Boots on the ground

It’s what Danny Lucchesi, Delicato’s group production manager, calls “boots in the vineyard” winemaking as only the “experience and education” of being out in the field can you really make better wine every year. “This is not calendar winemaking where everything is the same every year. You have to got to walk the vineyards every day,” he adds.

Which means it is no longer just the region for mass produced Zinfandel, where growers were happy just to produce grapes for others. It’s now very much the hip and happening place for winemakers to come to experiment and discover what can be done in California with different Mediterranean, and Italian, Spanish and German (Dornfelder) varieties in particular.

In fact whisper it gently but Lodi is not just famous for being California’s biggest wine producing region, it is also now responsible for 20% of California’s premium wines too. And that’s not a sentence I would imagine writing 10 years ago.

Then there’s this nice quote from Wine Spectator from David Phillips, co-owner of the region’s Michael David Winery: “It’s taken the next generation to turn what were once commodity wines into an art form.”

Under the radar

Old vines dating back to the 1880s are attracting more ambitious winemakers to Lodi

Lodi’s more under the radar profile also has its benefits in that it gives wineries and producers more freedom in what they do. “We are lucky with our economic model. We’re not like Napa where you would be crazy to plant Albarino,” says Spencer.

Whereas to buy some prime vineyard land in the Napa Valley might cost you over $400,000 per acre, you can pick up the same for closer to $30,000 to $46,000 in Lodi, says the Lodi Winegrape Commission.

It means the number of wineries in the area has boomed. From only around 10 in 2000, there are closer to 90 now, many of which are boutique producers looking to produce hand crafted, premium and super premium wines.

Lodi is also home to some of the oldest vines – dating back to the 1880s – in California. Gnarly Head is not just the name of one of its most famous Zinfandels, its how you describe the vines in these parts. Many of which were planted by some of the first pioneers who were attracted to the Gold Rush in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The challenge, admits Spencer, is to keep these old vines in production as the pressure is there to rip them up and replace with higher yielding varieties. He is, though, pleased, that there at least 2,000 acres of old pre-Prohibition, own-rooted vines across Lodi. Part of the Commission’s role, says Spencer, is “to elevate these vineyards, and make them more attractive to wineries across California”. “They are very much part of Lodi’s ecosystem,” he adds.

So much of the work he does is to connect the right growers and producers so that there is a healthy and profitable market for the grapes that these old vines are producing. It’s all very much about promoting the “personality” and “vineyard focused” winemaking that is going on in the region, he adds.

It’s why there are more winemakers from Sonoma and Napa making the trip to Lodi and investing some of their futures in the area.

Winemaker dinner Lodi style: here’s how they do it at Oak Farm Vineyards in this converted stables

Big boys roam

Lodi is still very much the region where all of America’s big producers, from E&J Gallo to Constellation, Delicato to Trinchero, source their bright, fresh, forward fruit either for Lodi-specific brands, but more likely to go into bigger, wider blends.

It was after all the region that became synonymous with the boom in demand for white Zinfandel in the 1980’s and 1990’s where every major producer could not get their hands on enough cheap fruit. It still claims to be the self-proclaimed ‘Zinfandel Capital of the World’ and accounts for 34% of California’s premium Zinfandel production.

It’s partly why the region has so many growers – 750 at the last count, many of whom are fifth or even sixth generation. All of whom you imagine know each other by their first name.

Spencer sees the early 2000’s as the time when the pendulum started to move in Lodi towards making wines that were more site specific. Ravenswood, for example, he says, was one of the first to put Lodi as the source for its white Zinfandel on the label.

Then came the success of the likes of Seven Deadly Zins “which began to define what we were”.

Ambidextrous approach

The seven different AVAs within Lodi allow winemakers to understand the kind of grape varieties they can work with in each zone

The key to Lodi’s future, claims Spencer, is that it “can do both”. If you want big, chunky, dominant red wines, then Lodi is the place to go. If you want to source bright fruit for your red blends then it can do that too. But, increasingly, if you want something a bit different, want to experiment and try something new, then Lodi has that covered too.

It means Lodi is both the source for Gallo’s breakthrough Apothic Red, sweet red blend, but is also providing it with premium fruit for its top blends.

Clay Station, part of the bigger Delicato group that is now distributed in the UK through Bancroft Wines, says the balance between commodity and premium is moving, but slowly, as still 85% of what it does is for mainstream wines.

The big difference, though, is the skill and ability of its growers to “look after the fruit” and ensure it is of the right quality it needs at whatever price point, says Pirie.

The key for a business like Delicato, which despite its size is probably only the ninth biggest operator in Lodi, is to be able to play at all levels, says Jonas Hillergen, Delicato’s regional director for EMEA. Be it Brazin, Noble Vines or Three Finger Jack.

“We were traditionally a big bulk player here, but now we have wines at all levels, from the mass volume through to private label and premium wines,” he says.

Spencer says the region has to come to terms with demand from both sides of the winemaking spectrum. There is certainly pressure to look at how average yields can be pushed up from five or six tonnes an acre to the more competitive 12 tonnes that the bigger players are looking for. For now its annual tonnage varies between 550 to 800 tonnes depending on the harvest. “So there is a lot of work being done on different vineyard techniques to be more efficient and produce higher volumes,” he says. Whilst at the same time staying true to its environmental and sustainable values.

“We have one foot in commodity and one foot in premium,” says Spencer. “But overall we would like to see us migrate more to premium winemaking.”

- You can read further reports in the coming weeks from Richard Siddle on the changing winemaking scene in California with specific spotlights on what is happening in Sonoma and Napa.