“The people are very important; they are as much a part of each terroir as the landscape and the vines,” Lyrarakis winemaker Myriam Ambuzer tells me.

I’m a bit of a geek when it comes to the Greeks. Caught cheating in a Latin exam when I was 14, I was banished to do Greek Civilisation O Level with who were rudely known as the ‘thick girls’. Greek Civ became my absolute favourite subject, and I was particularly partial to the Minoan civilisation, dating back to around 3000BC at Knossos on the island of Crete.

The Minoans were incredibly sophisticated, the first city state in Europe and the very cradle of Western civilisation, with complex systems of agriculture, trade and administration, and a highly cultured approach to the finer things in life.

Wine was central to Minoan life. Along with olive oil, it was an important trade commodity, and was central to religious rituals as well as secular enjoyment – feasting was important way of maintaining social cohesion, and the Minoans clearly did it very well.

From one generation to the next, wine has played a key role here. Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Crete’s capital city, has an extraordinary collection of artefacts excavated at Knossos which show how important wine was here. Vast clay jars, some as tall as a man, made for fermenting and storing wine; curvaceous jugs for pouring; delicate tumblers or coupettes for drinking. All are joyously decorated with geometric swirls and bold stripes; few would look out of place on a modern table.

Fast-forward a few millennia, through occupations by the Romans, Byzantines, Venetians, Ottomans and others, and Crete’s winemakers are still at it. Phylloxera struck here in the 1970s, wiping out native vines that were then replaced with more robust international varietals, or table grapes for raisin production. Co-ops ruled the roost until the 1990s, churning out bulk wines that understandably failed to raise much interest among discerning drinkers.

Since then, however, the next generation of growers has been turning its attention to quality over quantity, tradition over industrialisation, making their own wines or growing under contract for individual winemakers, and most of the co-ops have closed down. There are now around 50 producers on the island and their wines are increasingly exciting the palates of the global wine industry.

The importance of being local – grapes, place and people

Lyrarakis is widely acclaimed to have spearheaded the modern Cretan wine industry, garnering gongs from Jancis Robinson, Robert Parker (but don’t let that put you off), Decanter and sundry other arbiters of taste in the wine world. Established by Manolis Lyrarakis and his brother Sotiris in 1966 and now in the hands of their offspring, Lyrarakis has 15 hectares of vineyards on limestone/gravel in the mountainous region to the south of Heraklion.

Lyrarakis were the first producers on Crete to champion indigenous grapes, saving some from certain extinction. Dafni is one of these, traces of which have been discovered in Minoan wine vessels; Plyto is another, rescued from the jaws of obscurity when Lyrarakis planted it commercially in 1992. More recently the family has revived the Melissaki grape; currently nobody else on the island is growing it, but it has been found to be hardy and resistant to drought so shows great potential for our climate-changed future.

“These are difficult grapes,” says Effie Kallinikidou, Lyrarakis’s export manager. “There were no text books to show us how to grow them so we’ve learned by trial and error.”

Myriam Ambuzer is the winemaker here. Her father is Palestinian and mother Cretan; she worked with famed Spanish winemaker Pepe Mendozain Alicante before starting at Lyrarakis in 2002. “You could say that I grew up in the winery.” she tells me. “I’ve learnt so much from the people, the vines, the wines and the place. Every vintage teaches me something new. Each harvest is hiding a “bet” which we are determined to win, but also willing to lose in order to learn more.”

In addition to growing their own grapes, Lyrarakis works closely with around 100 other growers on the island. “We constantly research and experiment, mixing organic, biodynamic and more traditional practices which we adapt to each specific place, and to each farmer,” Ambuzer goes on. “The people are very important; they are as much a part of each terroir as the landscape and the vines.”

“All the native grapes we grow are important to sustaining the biodiversity here,” winemaker Myriam Ambuzer

Ambuzer often uses different vinification methods for the same wine – perhaps fermenting and/or ageing some in barrel, sometimes vinifying whole clusters, using short or long extractions. “There are no standard recipes, and they might change according to the vintage,” she says. “The wines all have an identifiable ‘trace’ of the varietal which is coloured by the vintage’s particularities.”

“All the native grapes we grow are important to sustaining the biodiversity here,” Ambuzer goes on. While they are not yet certified organic, sustainability is at the heart of all they do. Spraying is kept to a bare minimum – wild plants are used as ground cover in the winter which, along with sporadic sheep grazing, keeps weeds down in the vineyards as well as maintaining soil health, and the organic waste from the winemaking is aerobically composted to use on the vineyards.

In addition, Lyrarakis supports and invests in the people they work with, and the Cretan culture as a whole – they regularly sponsor local music and culinary events, and run education programmes for children as well as their staff and growers.

Manolis and Sotiris Lyrarakis have now retired but their five children carry on their work. The company underwent major rebranding and redefinition of its strategy in 2016, focussing on their pioneering work with native varietals and emphasis on Crete’s distinctive terroirs, and now export to over 20 countries.

Crete has an unbroken history of winemaking going back around 5000 years – it is one of the few regions of the Mediterranean to continue making wine throughout occupation by the booze-free Ottomans and/or Moors. “Cretans have always been rebellious,” Kallinikidou tells me.

“Crete sees itself as very different from the mainland – it only became a part of Greece in 1913 – and this sense of independence and local pride is still very strong.”

Lyrarakis seems to personify this spirit – respecting and reviving local traditions and adapting them with a very modern eye. I’m sure the revellers of Knossos and their wine gods would approve.

So how were the wines tasting?

The full line-up for the tasting – and what a setting!

Vilana 2018

Vilana is Crete’s most widely planted white grape and here makes a very easy drinking wine at a really good price. Heady-but-not-sickly floral aromatics snapped into shape with a bergamot-like zest. £7.45

Kotsifali 2018

Kotsifali is the staple red grape of Crete, named from the Greek word for the blackbirds who nest in the vines. This has very friendly, plum-crumble fruit with brandy-snap spice lifted by a savoury, bracing finish. £7.45

Lyrarakis White 2018

Vidiano is known as the ‘chardonnay of Crete’ – versatile and able to thrive in various climates. Here it is blended with the local muscat of Spina grape in this fragrant wine, cut through with grapefruit and juicy lemons with a gentle 12% abv. Cries out for a fried fish lunch. £8.35

Lyrarakis Red 2016

Local grape kotsifali is mixed with reassuringly familiar syrah, partially aged in oak, to give this modern red, meaty on the nose with juicy dark fruit, black pepper and a lovely fresh acidity. £8.80

Assyrtiko, Vóila 2018

Way over on the east of the island, Vóila is a now-abandoned settlement established by Venetian occupiers in the 15th century. Assyrtiko – originally from the volcanic island of Santorini – was planted on the limestone soils of its surrounding vineyards by the local co-op in the 1990s, and Lyrarakis has been working with local growers here since 2011. At at altitude of 580m, the fruit ripens more slowly than on Santorini, giving great concentration of rosemary and preserved lemon notes balanced by a saline, stony minerality. £8.55

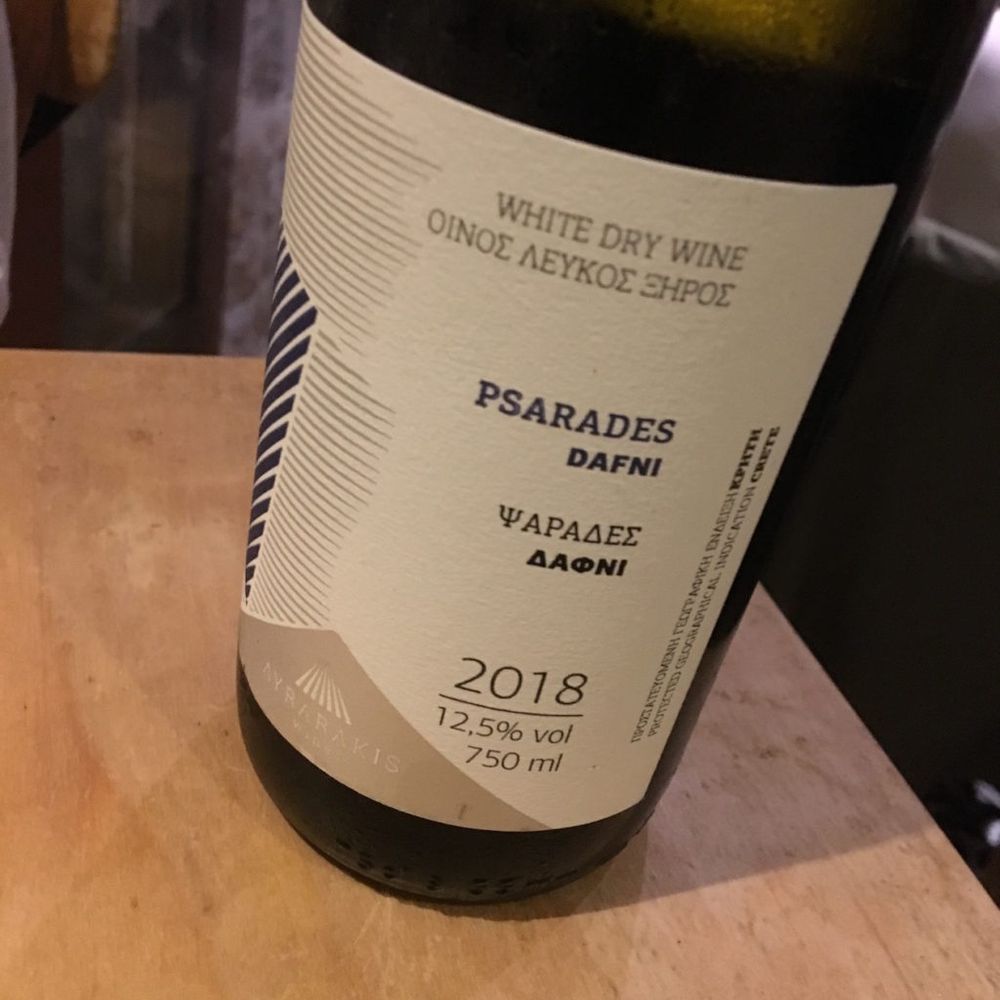

Dafni, Psarades 2018

Dafni has an incredible aroma of what at first appears to be ginger but, on second sniffing, clarifies itself as bay leaf, after which the grape is named. Grown on vineyards just 15km south of Knossos (be still, my beating heart), this is full of heady mountain herbs with a dazzling acidity on the finish. A really distinctive wine that lingers on the memory long after it’s gone, it’s also very food-friendly, proving an ace match with tricky asparagus and much more beside. £8.57

Plyto, Psarades 2018

The Psarades vineyard was harvested three times at different levels of ripeness to bring the right balance to this tricky grape. Lean and lemony with a salty twang thanks to sea breezes from the coast 30km away, this much-lauded wine has real purity of aromatic fruit and a luscious, silky mouthfeel. £9.27

Liatiko, Aggelis 2017

Gently crushed grapes, from bush vines up to 100 years old, are layered with whole bunches and some raisined grapes in 225 litre open barrels to kick off spontaneous fermentation, then transferred to s/s tanks. Concentrated aromas of plummy fruit, oregano and nutmeg give way to a really invigorating finish. £11.70

Thrapsathiri, Armi 2017/18

Thrapsathiri, another native grape, grown on the Armi vineyard at 500m, is fermented in a mix of American and French barrels after 12 hours’ skin contact, then left on the lees for two months. Concentrated with textural layers of mint, rosemary and honey, I wrote ‘very cerebral’ in my notes. One to ponder on. £12.65

Vidiano, Ippodromos 2018

From the Ippodromos vineyard (ippodromosmeaning a horse racing stadium) at 610m, the grapes are harvested twice, about 3 weeks apart, and are fermented and aged in old and new barrels. Lychees and peaches with a forthright thrust of oak. £12.65

Liastos

Plyto, assyrtiko, thrapsathiri, dafni, vilana and vidiano are left to dry in the sun for two days, then for a further 7 in the shade before fermentation and ageing in oak. This multi-medal winning sticky has beautiful, opulent fruit underpinned with the clean, refreshing acidity found in all Lyrarakis’s wines. £10.55 half

Wines from Lyrarakis’s three ranges are imported into the UK by Fields, Morris & Verdin/Berry Bros & Rudd. Prices above are DPD.