Sashi Moorman is an operator and collaborator extraordinaire, representing not one winery but three – and even that is not his whole portfolio. (He also works as a consultant and is co-owner and winemaker at Evening Land in Oregon.)

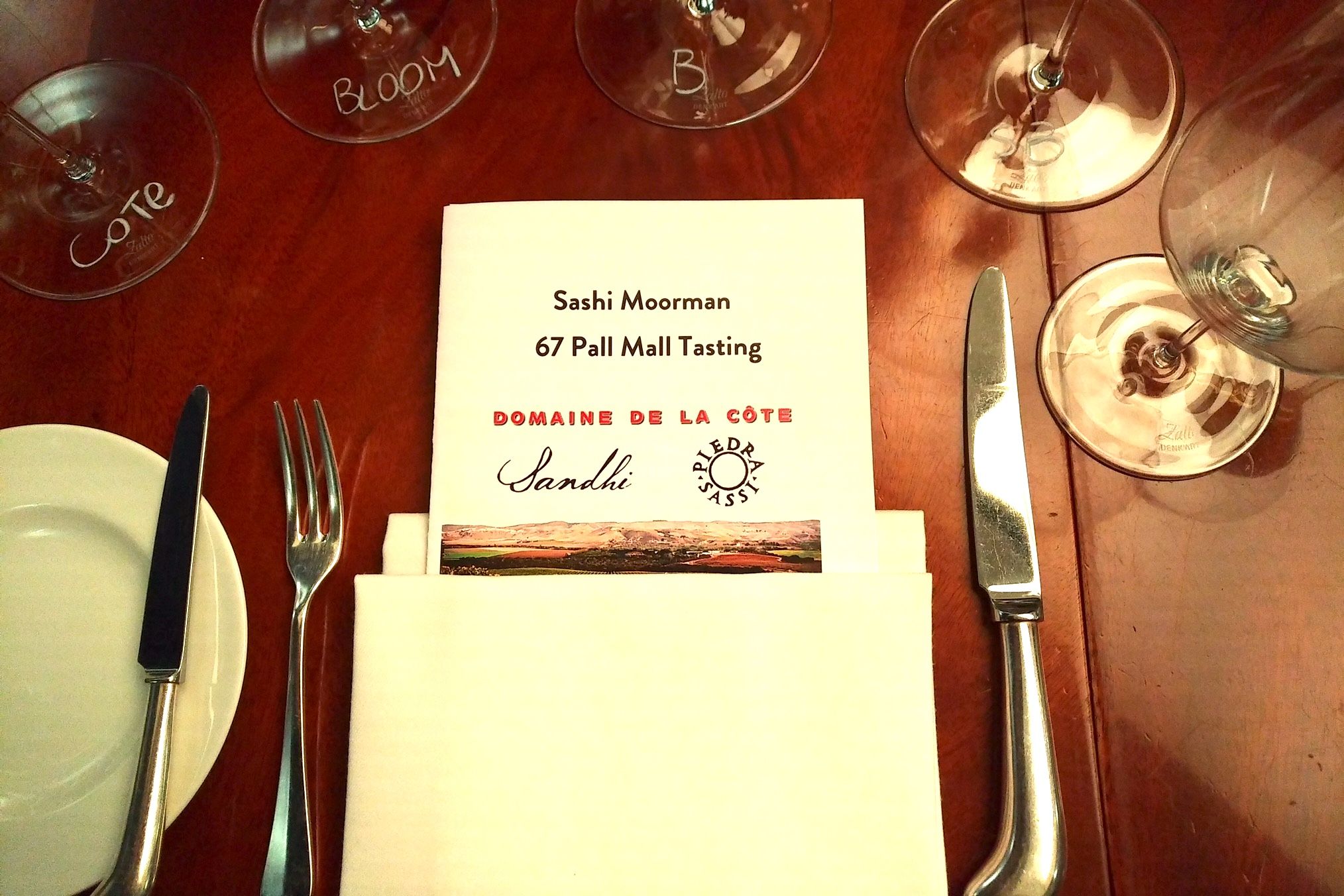

Sashi Moorman, London’s 67 Pall Mall, February 2018

This week, however, Sashi Moorman is focused on the three estates where he makes wine on California’s cool central coast: PiedraSassi, Sandhi and Domaine de la Côte. The latter two are collaborations with Rajat Parr, the San Francisco star sommelier turned winemaker, while PiedraSassi, both winery and bakery combined, is Moorman’s family project, run together with his wife Melissa. Moorman is in town to introduce the 2015 single-vineyard wines of these three estates during a luncheon at London’s 67 Pall Mall.

- “Sandhi,”in Moorman’s words, “is the brainchild of Raj Parr” who was on a mission to “find a place where he could grow Chardonnay at the level of fine Burgundy.” This turned out to be the Santa Rita Hills that share the latitude of Tunisia and the heat summation of Champagne. Sandhi’s focus is on Chardonnay. 2010 was the first vintage

- Domaine de la Côte, also in the Santa Rita Hills, is “all about this place with unique souls but a very harsh climate” and is dedicated to Pinot Noir. It was started in 2012.

- PiedraSassi, on the other hand, is slightly further inland and focuses on Syrah in the AVAs of Arroyo Grande, Ballard Canyon and Santa Maria Valley. It is “the winery I have been working longest with,” says Moorman who started this project in 2003.

Moorman’s mind is clearly fizzing with facts, ideas and opinions. The benefit of this is that he gives a very candid take on contemporary Californian winemaking where everybody talks low-intervention but tinkers nonetheless.

We start with the Sandhi wines and then talk in-depth about the winemaking styles

Sandhi, Chardonnay, Sanford & Benedict, Sta. Rita Hills, California, 13%, 2015: A smoky, hazelnutty nose opens into the aroma of candied lemon peel. The palate is taut and reveals a deep streak of electric lemon freshness, the smokiness returns on the long finish.

Sandhi, Chardonnay, Bentrock, Sta. Rita Hills, California, 13%, 2015: Very flinty and reduced but on the palate there is textural richness and a pervasive Amalfi lemon ripeness, brilliant and taut, long and resonant.

Moorman’s frankness was refreshing.

Here is some of his commentary: Talking about the two very different Chardonnays, Moorman states blankly that “Sandhi is a négociant. We don’t farm our own grapes,” before adding that this is a good thing since “Chardonnay benefits from benign neglect.”

He is only half joking: and explains that relatively poor farming results in nutrient poor grapes – something that he and Parr like as it helps them create their reductive style. Terrible-looking Chardonnay grapes do not bother them since the juice is almost immediately separated from the solids; the state of the grapes is far less important than with Pinot Noir.

He describes the vineyards the grapes are bought from. The north-facing Sandford & Benedict vineyard, where it all started for this region in the 1970s, Moorman explains is colluvial soil made up of slope wash from the mountains and periodic flooding of the river. It is well-drained but rich, its north-facing aspect helps to retain the brilliant acidity apparent in the wine. It is this relative richness of the soil that explains the absence of the heavily reduced aromas: there are enough nutrients in the soil and therefore in the fruit to ensure a stress-free ferment.

With Bentrock, where soils are semi-metamorphic and contain a lot of quartz, decomposition and weathering is slow, so there is little clay to hold either water or nutrients – which is ideal for the style of Chardonnay Parr and Moorman want to make. They ferment the parcels separately in 500l puncheons at temperatures up to 32°C. This relative heat does two things: it helps to create more of those flinty, reductive aromas which are created when yeast experiences nutrient stress during this metabolic process, it also causes the yeasts to reproduce faster thus more lees are created during a warmer fermentation.

“They really help to achieve texture which in turn helps to balance the acid,” Moorman explains.

The fermented wines are kept for 14 months in barrel on their gross lees, without any additions of sulphur. Moorman emphasises that there is no batonnage. The first sulphur addition only comes when the Chardonnays are moved to tank, with successive further small additions, all depending on the development of those desirable reductive aromas.

“This is where we start to asphyxiate the wine,” is the way Moorman puts it.

While the environment of the lees in the barrels is reductive in itself and protects the wine, once the wine is in an inert tank and is sulphured, there is progressively less dissolved oxygen and the reductive flavours become stronger. They stop at a desired point and start bottling. The technique [of gradually adding SO2], Moorman says, “is borrowed from Jean-Marc Roulot.”

So while the sites are different, and the wines are treated in the same way, the winemaking definitely helps these wines to become so very different. While additions are minimal – only sulphur-dioxide – it is winemaking that creates a whole new emphasis. A whole box of tricks is thrown at them – not by must adjustment, yeast or enzyme addition but by winemaking techniques.

“Red wines lose their baby fat as they age whereas white wines become rounder, so we realised we needed to start with a very lean wine,” Moorman says about these single-vineyard Chardonnays that are designed to age.

Before the Pinot Noir and Syrah are poured, Moorman opens up about the different approaches with the red wines

In terms of farming, Pinot Noir is a polar opposite – here contract farming holds few benefits and the key is having control of the vineyard. With Domaine de la Côte Moorman seems far more emotionally invested here, having planted these vineyards. When he talks Chardonnay it is all technical insight and mastery, with Pinot Noir he is more philosophical and talks about his own wonder at how homogenised his Bloom’s Field vineyard has become, despite having been planted with Calera, Mount Eden and Swan selections in alternating rows. He also reveals some of the discussions he and Parr have surrounding their winemaking.

Moorman parodies one of their conversations: Parr: “We don’t know if these vineyards are great, you cannot presume that they are.” To which Moorman says he responds by saying: “But we have to!” All this stems from Rajat Parr’s thinking: he observed that most people have the same assumptions when they plant a new vineyard in the New World. People put so much effort and means into planting that they work on the assumption that their vineyard is great. They then end up applying techniques from world class winemakers in the Old World to inferior grapes which, according to Parr, results in “overwrought” wines. Hitherto Moorman and Parr thus proceeded with caution.

However, 2015 changed all that. “2015 was a watershed vintage for me and Raj,” Moorman says. “Previous to that we were a bit shy. The yields were so low that it forced our hand in making concentrated wine. 2015 was a gift for us.” Because in previous years not all ferments would go through, in 2015 they decided to start a pied de cuve, or yeast starter, from their own grapes that would get the other ferments going. They also became more active: “We did more punch-downs, in previous vintages we only did remontages.” Moorman is frank: “There is a fear of doing too much, of overextraction. But now we’re so much more confident of taking what is there.”

Such talk is far more honest than constant piping of “low-intervention”.

Domaine de la Côte, Pinot Noir, Bloom’s Field, Sta. Rita Hills, California, 13%, 2015: from a site with weathered, iron-rich shale. Apart from the portion of the pied de cuve, all of the ferment was whole-bunch. The nose has the typical Sta. Rita Hills savouriness of wet briar and white pepper. It is fragrant and ethereal on the nose. On the palate the fruit is lush, super smooth and reminiscent of mulberry. The structure is taut and the finish has some stemmy tannins. Glorious.

Domaine de la Côte, Pinot Noir, La Côte, Sta. Rita Hills, California, 13%, 2015: from a site with heavy rock but porous soils which has richer clays. Also 100% whole bunch apart from the pied de cuve. The nose is less forthcoming and needs time to open up. There is something visceral like blood and a leafy notion from the stems, while the palate holds a still tight, compact core of luminous red fruit, framed by tinglingly fresh acidity. It has all the makings of velvety pleasure in years to come.

As time runs out, Moorman is less voluble about the PiedraSassi wines but explains that the Syrah from the Rim Rock vineyard of weathered shale has been top-grafted onto former Chardonnay vines that were planted in 1988, while Syrah was top-grafted on old, own-rooted Riesling vines that had been planted in 1973 and 1988 in the Bien Nacido vineyard which has deep alluvial soils. Both Syrahs are also fermented 100% whole bunch with a pied de cuve.

PiedraSassi, Rim Rock, Syrah, Arroyo Grande Valley, California, 13.5%, 2015: Violets and blood on the nose, this is heady stuff. The body shows lush ripeness of fruit, corseted by lovely acidity. Luscious cherry comes to the fore while fine, ripe tannins coat the mouth.

PiedraSassi, Bien Nacido, Syrah, Santa Maria Valley, California, 13.5%, 2015: This is wild and peppery on the nose while waves of floral-tinged fruit unfold on the palate. This is balanced and finely dovetailed with velvety tannins, ripe fruit and lovely freshness.

These estates are represented by Roberson Wines.