The first single vineyard Sauvignon Blanc at Cloudy Bay was called Cloudy Bay Greywacke Vineyard. It was then that Judd registered the name Greywacke, just in case he ever needed it in the future.

When Kevin Judd finally decided to leave Cloudy Bay in 2008 and set up his own winery, Greywacke, his leaving present was… a coffee machine. Judd lets that information hang in the air a bit.

Judd had been the founder winemaker at Cloudy Bay, overseen 25 vintages and put the winery (and indeed Marlborough itself) on the map before it was bought out by LVMH.

He smiles wryly at the memory. “I thought I’d get a TAG (they make them you know) but I got a coffee machine… I’ve never worn a watch since.”

“You’d never have worn a TAG Kevin,” Judd’s wife Kimberley pipes up.

“True, but I could have sold it and bought two coffee machines.”

“After 25 years at Cloudy Bay I decided to do something different, trying to make a style that was very specific – much lighter. I wanted to move away from ‘green herbaceous’ Sauvignon Blanc, not that it’s not good it’s just not the style we wanted to make.” Kevin Judd, London, January 2019

An audience with Kevin Judd is an immensely illuminating and entertaining affair. Celebrating 10 years of his own label, Greywacke (pronounced Grey-wacky), by opening different cuvées to represent every vintage, he delivers a masterclass in winemaking technique punctuated by some often unpublishable stories – all handed down with a dry, laconic wit. He reminds me of the kid at school who always sat at the back, was the first to grow sideburns and smoke tabs and yet was clearly the smartest kid in class.

Would we see him on stage at the (then forthcoming) Sauvignon Blanc 2019 Symposium in Blenheim? “Nah, I’d been asked to but life’s too short you know,” he smiles. At the actual event I noticed he didn’t miss one of the presentations over the three days, nor it seemed, any of the evening functions.

The truth of the matter is that Judd is a man of few words, doesn’t like hogging the limelight and, most likely, isn’t immune to a touch of stage fright.

“Going back 25 years ago I can remember how horrified I was presenting the 10th release of Cloudy Bay at The Ivy. Good thing is that I am relaxed here and not shitting myself like I was then… I even had a jacket and tie on.”

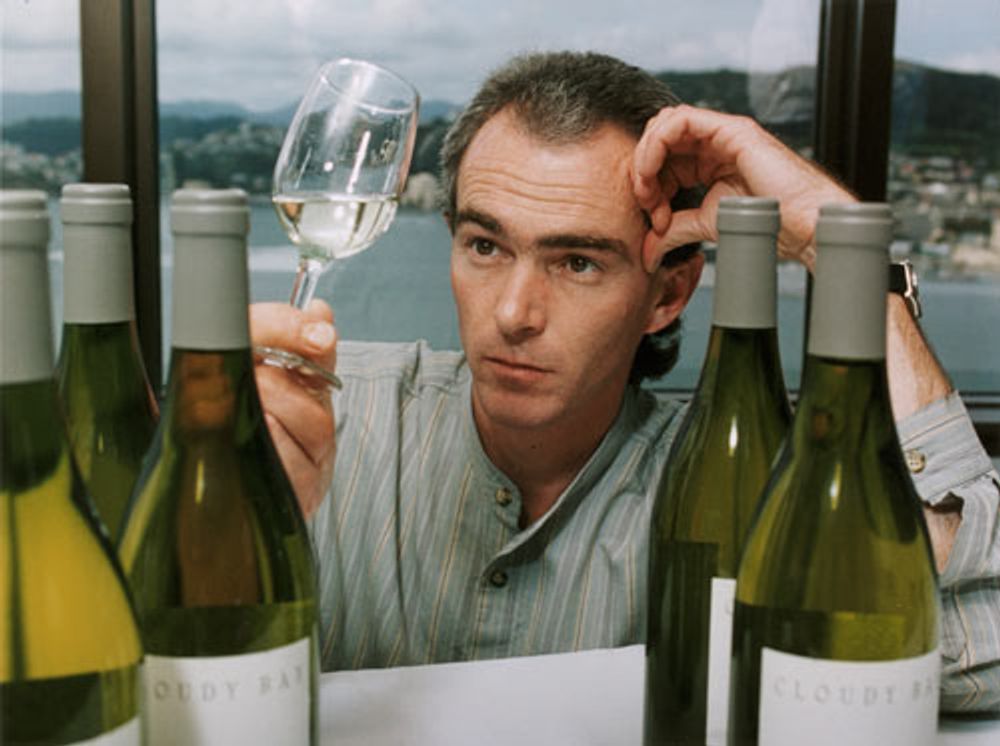

Dreaming of a coffee machine: Kevin Judd putting Cloudy Bay and Marlborough on the map in the 1980s

Going it alone – leaving Cloudy Bay for Greywacke

When it comes to winemaking Judd is deadly serious, a quiet pragmatist whose eye for beauty is as much evident in each vintage he makes as in each photograph he takes – he’s a published and exhibited photographer who spends a third of his time capturing the beauty of nature (all the Greywacke labels are his images). When he talks about the wine style he set out to achieve after leaving Cloudy Bay it is very visual in its delivery. He likes to see “golden grapes, open canopies, dappled light on the fruit.”

Greywacke produces seven wines – two styles of Sauvignon Blanc, a Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, Riesling and Botrytis Pinot Gris from a team of six people.

Richard Ellis joined the team two years ago from Negociants UK, overseeing sales and marketing to the 40 countries Greywacke is distributed in. 96% of the wine is exported from New Zealand with the UK the top market and the US second. Ellis’s arrival means Judd can keep his focus where he has always wanted to – in the winery.

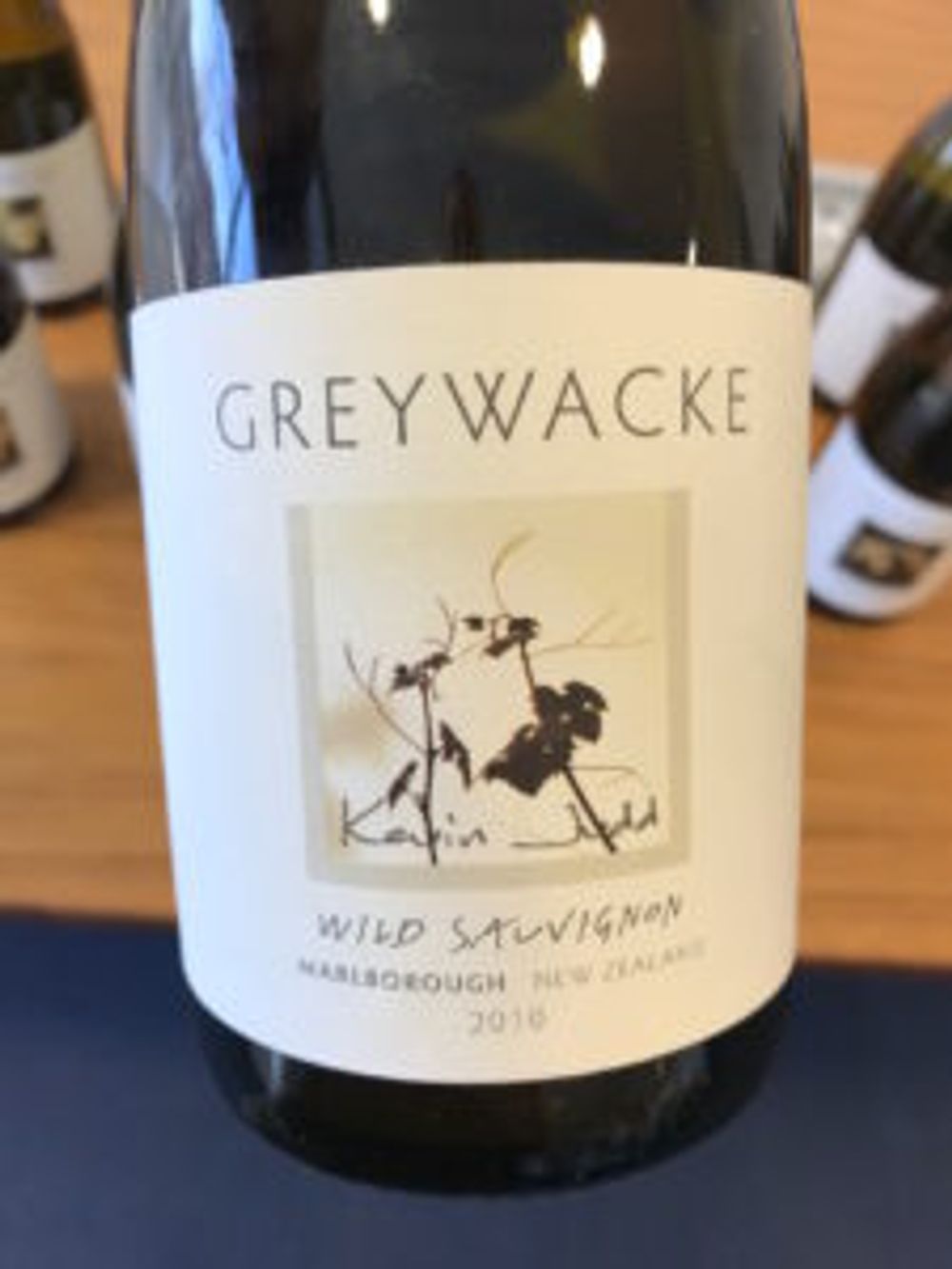

If the 1980s cult New Zealand wine was Cloudy Bay, arguably today’s cult New Zealand wine is Wild Sauvignon, Judd’s oak-aged, minimal intervention Sauvignon Blanc that he rightly calls his signature wine.

He has always been an experimenter, he produced a single vineyard Sauvignon Blanc as early as 1993, which came from the Greywacke vineyard and was released as Cloudy Bay Greywacke Vineyard. It was then that he registered the name Greywacke, the wine being then named Te Koko after that.

“I registered it in case I needed it but, to be honest, I never thought I’d leave Cloudy Bay. But then they offered me an ambassadorial role not a chief winemaking role… so that was a bit different.”

The additional turning point was 2008 when the bountiful harvest was 25% up in volume.

“There was an instant over-supply, the price of grapes dropped, the price of land dropped. Ivan and Margaret Sutherland (Dog Point) looked for people to sell grapes to and said if you are going to do your own thing we have room in the winery.”

“When I resigned I stayed on at Cloudy Bay as a consultant winemaker and everything apart from the Pinot Gris I bought from the Dog Point team – six or seven contract growers and about one and a half hectares ourselves.”

“I still don’t own the winery or substantial vineyards but I’m happy where it is I’m not going back to an HR scenario. I don’t want it to be much bigger. I’m happy and…. I have a new coffee machine.”

Judd watching a video about Greywacke on its 10 year anniversary, London, January 2019

How Greywacke has allowed Judd to take a walk on the ‘wild’ side

“After 25 years at Cloudy Bay I decided to do something different, trying to make a style that was very specific – much lighter. I wanted to move away from ‘green herbaceous’ Sauvignon Blanc, not that it’s not good it’s just not the style we wanted to make.”

“We go for about 10-11 tonnes per hectare – so we get ripeness, concentration and texture, aiming for subtle, ripe, non-aggressive, a nice, delicious drinking fruit style. I like be to able to see the fruit as you walk past the vines and not have to look inside the canopy, you get slightly lower acidity but then I like grapes that are golden not translucent green, I’m looking for something more subtle.”

Because Sauvignon has thin skins Judd picks by machine at night – so long as the fruit is clean – aiming for about 700 litres per tonne (the average in Marlborough is 750), “a low extraction rate to keep the phenolics down.”

Surprisingly, given his importance within the New Zealand wine industry, Judd owns very little land and no winery, leasing most of the vineyards off the Sutherland family, other fruit is obtained from 12 blocks, all within the central Wairau Plains and the Southern Valleys.

“It’s not a site thing, there is no science or precision about what blocks go into which wines. With the Wild Sauvignon the fruit is on the riper end so we tend to make the decision ‘on the fly’ at harvest. Sometimes it might be fruit that doesn’t fit into the barrel so that becomes the batch, but we always make more than we need – sometimes we go very funky and sometimes not.”

“We put it in the barrel and go and find something else to do, and they don’t teach that at Roseworthy,” (the college where Judd studied winemaking).

Greywacke is the name given to a type of sandstone that is a common bedrock in Marlborough

Wild Sauvignon, which is made in a hands-off style with naturally occurring yeast, was one of the first alternative styles of Sauvignon in Marlborough – both intricate and textural in style. Judd likes to tell a story of receiving a letter of complaint “‘How dare you put Sauvignon Blanc in oak?’ he said ‘if I wanted that I’d go and buy an Aussie Chardonnay.”

Judd explains that it is not one type of yeast he’s dealing with but a ‘zoo’ and he doesn’t achieve this using a bucket in the vineyard as some ‘wild fermented’ wines are.

“The yeast is already in the juice so we just wait. It’s not just a single yeast either – the yeast at the beginning is not the yeast that does the work and not the yeast that you get at the end, it’s like a microbiological zoo which is where you get a lot of the savoury flavours once fermentation takes place and the alcohol increases.”

“Most will go to 10-30 gms of residual sugar into winter and in spring fermentation starts again, we check for malo, 2/3rds goes through malo which softens the wine, lowers the acidity and gives it more weight, breadth and savoury-ness.”

Judd says he hates a malolactic character in wines.

“We stir Wild the most after malo, we keep stirring the lees, which is the thing to do to avoid a malo character.”

“Good thing is that I am relaxed here and not shitting myself like I was then… “

Judd also confesses to being baffled about how comparatively little Chardonnay he sells compared to the Sauvignon Blanc.

“We make much more Sauvignon Blanc than anything else – we try and produce what the market wants – but it’s a continual frustration that in the US we sell just 1% of Chardonnay compared to Sauvignon Blanc and in the UK about 7% even though it’s been said it is the best wine we make. But selling Marlborough Chardonnay is not like selling Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc.”

Judd’s style of winemaking with the Chardonnay is similarly hands-off, using 100% wild yeast. They use Mendoza and Clone 95, varying the proportions according to the vintage, go straight to barrel or tank, with 100% solids. 20% of the fruit is fermented in heavy toasted French barrels where it will spend 18 months, go through full malo in order to get the acidity in balance, to about 6.5. The wine is bone dry and very lean. “It’s the terroir,” he explains.

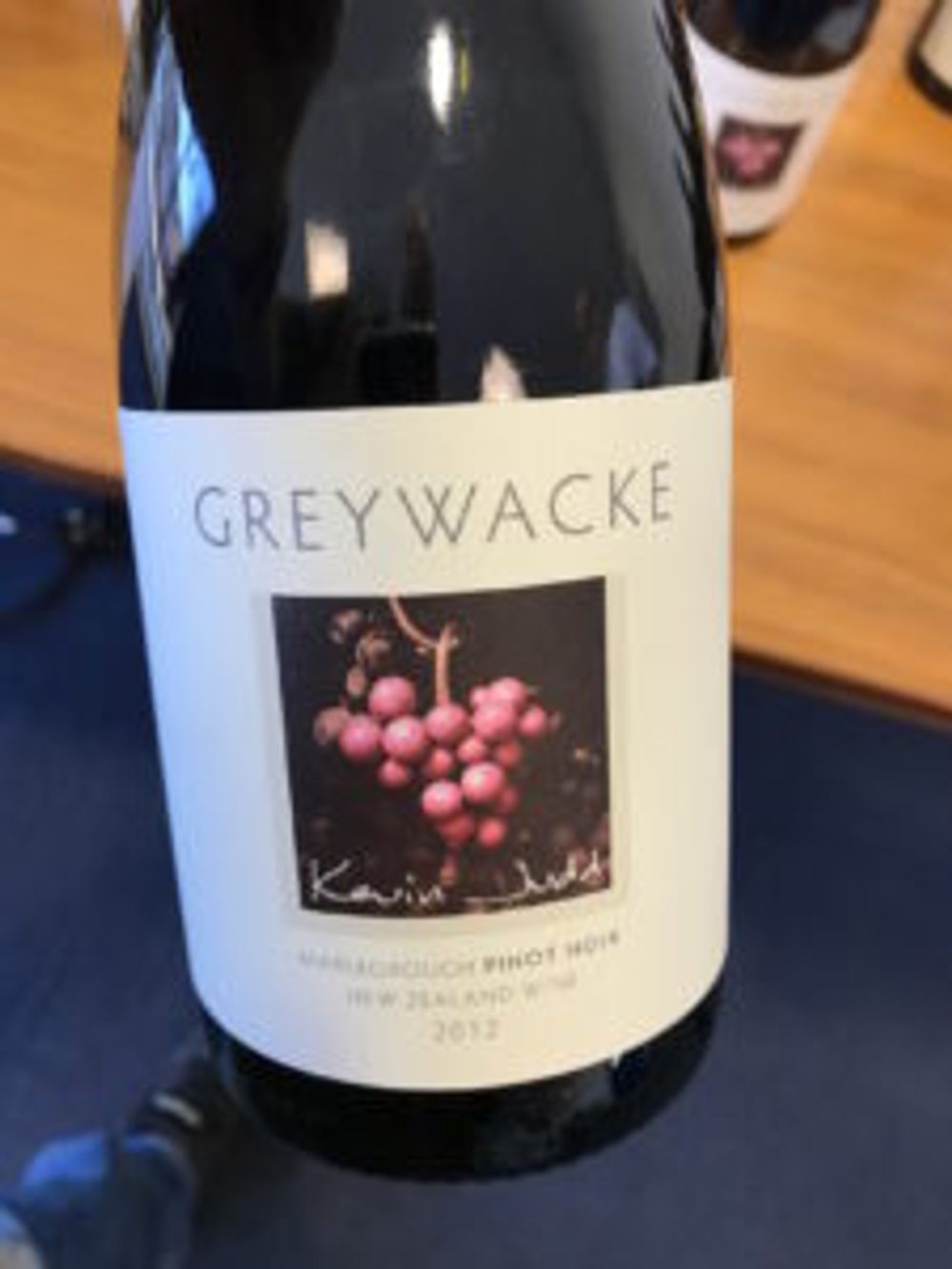

It was picking the wrong terroir by a lot of winemakers that has held Marlborough Pinot Noir back but that is now changing as the best sites are being exploited. Judd goes for a brightly aromatic style with 20% whole bunch and skin contact for three weeks. The wine is in the barrel for 18 months, 30% new. With his Pinot Gris he is going for the riper end – Mission clone rather than Geisenheim which is what a lot of New Zealand Pinot Gris is.

And so we move onto the 10 year wine tasting itself

Judd had chosen to start this remarkable tasting with the first and most recent vintages of Sauvignon Blanc and then chose two vintages of each of his other wines, except with the stickies at the end – one a Botrytis Pinos Gris the other a one-off wine, a late harvest Gewurtztraminer.

The three wines I’d want in my cellar are Wild Sauvignon 2010, Pinot Noir 2012 and Chardonnay 2011. But here’s the list in full:

Sauvignon Blanc 2009

Still hanging in there after all these years. Attractive nose, soft palate with plenty of finesse; ripe orchard fruit, apple compote, nice limey edge, good acidity, feels lean with a tidy, soft finish.

Sauvignon Blanc 2018

A tricky vintage in Marlborough, the warmest on record for the country as a whole and the second warmest for Marlborough. In addition, January was the warmest-ever for the whole country and it was the wettest-ever February.

The wine is so light it is almost see-through. It is young and clearly ‘much more Marlborough’ – a touch of sweat on the nose; on the palate is very bright, ripe, tropical fruit without being tutti-frutti, and drier than the nose would lead you to believe. 10% wild ferment brings a bit of mid-palate texture.

Wild Sauvignon 2010

Light golden; complex aromas, savoury, herbaceous, with a slight acacia, candy note. Terrific, layered fruit core on the palate: ripe red apples, apple skin, pineapple. Quite intense and joyful. Wine of the tasting?

Wild Sauvignon 2016

Lean, not really woken up yet, less funky than a lot of vintages. The mouth is lean and feels a bit skinny – needs time to broaden out a bit.

Chardonnay 2011

Very smoky and plenty of gunflint – feels very Burgundian with still a long of way to go. Nice mix of grapefruit acidity with nutty richness. The wood is well integrated but still very much there; nice rich layers of fruit, lovely length, touch of heat on the finish, with a lick of tingly mineral acidity on the finish.

Chardonnay 2015

Slightly reserved nose, wood is less present than 2011 (weirdly); just ripe orchard fruit, juicy, mouth-watering, bright, focused, quite closed.

Pinot Gris 2013

With just 8-11 gms residual sugar this feels like a demi-sec. Ripe, generous, very easy drinking.

Pinot Gris 2016

More closed on the nose than the 2013 – lovely rich, ripe, unctuous, voluptuous; great finish, complex flavours on finish.

Riesling 2014

Hand-picked fruit from 20+ year old low-yielding vines this is a real yin/yang wine – the acidity is not that high but is still very crisp. Bit of oily rag on the nose,

Delicious ripe, honeyed fruit.

Riesling 2017

Because of the difficult weather there were only 50 cases produced.

Almost Japanese nose – sake, nashi pear, bit of honey, not all there.

Very acidic in mouth, quite well balanced, flavour-profile not as impressive as the 2014.

Pinot Noir 2012

Showing some sign of ageing – slight ruddiness on the edges.

Fruity, deep macerated cherry, lovely texture, savoury richness. Terrific depth and elegance about the wine

Pinot 2015

Rich but also fresh, elegant and quite restrained, great texture and acidity. Black cherries, bit of damson jam, Asian spices. Needs time in the bottle, if you can keep your hands off it.

Late Harvest Gewurtz 2009

A one-off this is fantastically rich, unctuous, delicious, rich fruit, great acidity. The nose is pure rose petals and Turkish Delight.

Botrytis Pinot Gris 2015

Very Alsatian. Rich, unctuous, touch of cheesecloth on the finish.