Robert Dougan recognises himself that buying a vineyard when he knew little about wine production, or winemaking, might have been considered a foolhardy decision. But it is one that has paid off in spades since he and his wife Karine, who is from nearby Montpellier, snapped up an 11-hectare vineyard between Jonquières and Aniane at the heart of the Southern French wine revolution that started back in the 1970s.

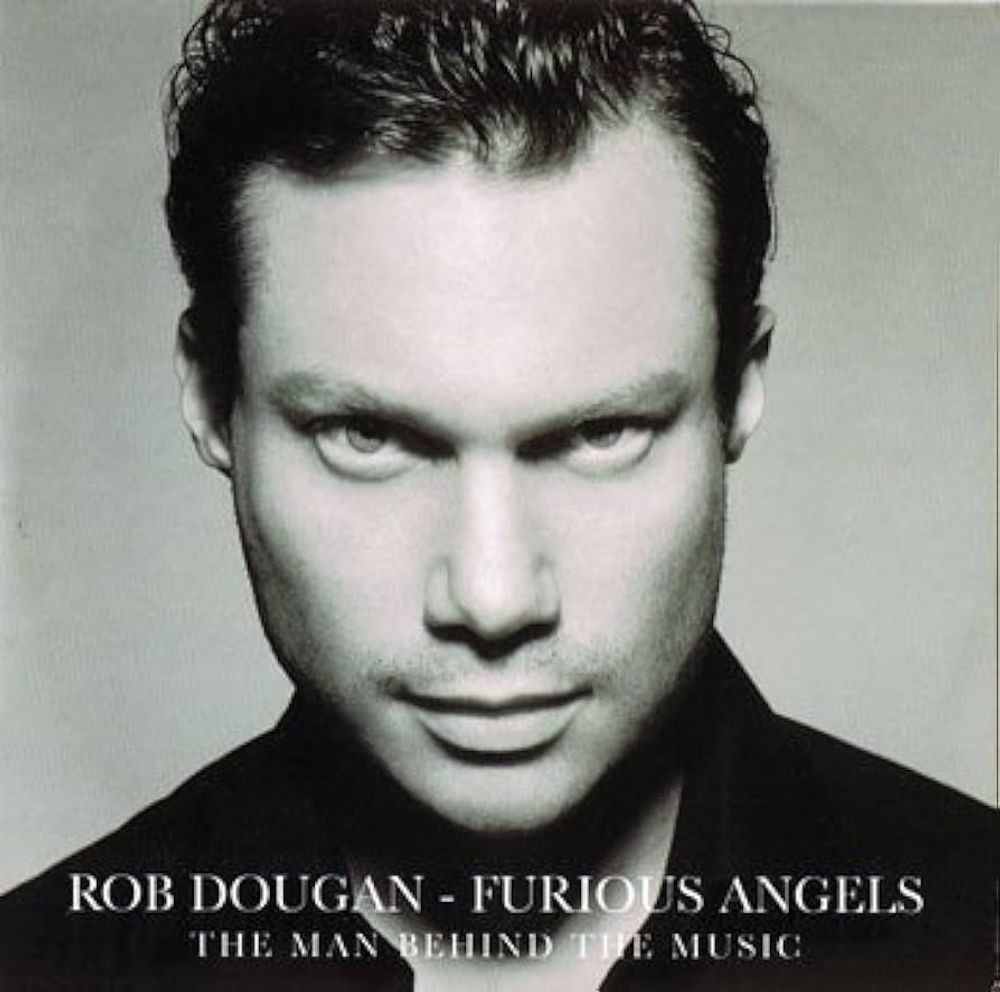

The young Dougan originally harboured ambitions to become a Shakespearean actor, but this dream was thwarted after being thrown out of Sydney’s National Institute of Dramatic Art. Like many young Aussies before him, Dougan found himself scrubbing dishes in London throughout the early 1990s while struggling to make it in the cut-throat music business. However, songwriting success did not elude him for long; his most famous single, Clubbed to Death, was released in 2003, while an album, Furious Angles, followed soon after.

Robert Dougan is a firm believer in "whatever you are going to do, do it well”.

“I really don’t know what possessed me to think we could do something,” he muses about his decision to buy the vineyard. “Maybe it was because it was my wife’s region, maybe because it was a beautiful site. I was there only last week, and with the dramatic mountains, the dark rain clouds and the spring flowers emerging, it was something to see.”

But 20 years ago, the ne’er sayers were out in force, full of gloom for the fledgling venture, predicting that it was nigh-on impossible for someone with no experience of the sector to make a go of it.

“There were probably some people questioning my sanity. Certainly, the banks weren’t very interested, but in retrospect, making interesting, high-quality wine is not only worthwhile in itself, [but] it is a very good idea to adopt your model. It’s always good to do high-quality work, even if it’s not the easiest. Sometimes, going against the grain works, as it’s slightly less competitive and even if it goes badly, you’ve gone down the path of least resistance," he says.

“We started off with the belief that excellent vineyard work was the key, and that should be our sole focus. I believe in whatever you are going to do, do it well”.

Impulse decision

Undeterred by the dissenting voices, Dougan made an offer for the plot of land on the spot. “Later, when I was travelling in the region, I noticed various old and often converted wine buildings. And I gradually learned that this was France's oldest viticultural region from Hugh Johnson’s book on the wine history and discovered that southern France was experiencing a huge kind of wine renaissance.”

While he admits to having the “general approach of an 11-year-old boy to most things”, he believes the most important element of winemaking lies in the vineyard itself. “I think that with the history of the wonderfully old vineyards planted years ago, we are almost museum attendants. All the hard work has already been done.”

The vineyards at La Pèira

Inspired by what he had read and seen of the region, he set about working on the estate but admits they were ill-prepared for the reality of the first grape harvest.

“We started off in such an un-businesslike manner; we really weren’t part of the established wine business. During the first vintage, we were so focussed on the vineyard work that even six to eight weeks before harvest, we had no building, nowhere to receive the grapes, and no space to vinify and no equipment. So that was a bit unusual.”

In the nick of time, they found a small stone building between Daumas Gassac and Grange des Pères to work in. Some tanks and equipment arrived several weeks before harvest and fortunately, things began to fall into place.

Right place, right time

“I’m not sure many would have had great confidence in us at that point. And many didn’t for some time. But it all rests on discovering a great vineyard completely by accident. The La Pèira cuvée is grown in a certain vineyard, the Bois de Pauliau. One hundred yards from that plot, we have vineyards that don’t produce quite the same quality of wine, or wine with the same qualities. It was all by chance.”

While there is clearly some luck at play, Dougan is surely being somewhat disingenuous in dismissing the part that sheer hard work has played in La Pèira becoming the success it is today.

He says he is a big fan of just getting on with things. “It’s often best just to crack on; there is a real magic in just starting something. It’s like having a child — there is never really a right time.”

Back in the early days, Dougan presented the first few vintages at an off-piste tasting in Saint-Émilion as part of the En Primeur tastings at the wine merchant Comptoir des Vignoble. An American négociant, Jeffrey Davies, who had studied oenology at the University of Bordeaux under Émile Peynaud, tasted the wine.

“He was incredibly enthusiastic and said he was going to present them to Robert Parker to taste the next day. Which they did, and he said they were the greatest wines from the region he’d ever tasted.”

Meanwhile, Dougan posted wine critic Andrew Jefford, some of the early vintages, and he sang their praises, writing in The World of Fine Wine that the vintages had “rearranged my inner pantheon in the way that truly great wine can".

“So that was a good start,” says Dougan in a typically understated fashion. “But more than that, both were a lifeline and meant we could continue on.”

Matter of record

La Pèira's big break came thanks to how well its wines were reviewed by Robert Parker in the US and Andrew Jefford in the UK

And continue they did, going from strength to strength with each vintage. Dougan believes that part of the estate’s success lies in the fact that his entire winemaking philosophy is diametrically opposed to most of his peers, “which is to make it about themselves,” he says.

“To make it about their tastes and their likes and dislikes. We set out [to] try and capture what is there as purely as possible. In music terms, we’re the recordist. We’re the person who sets up the microphones and records the music. The recordist doesn’t stop recording to ask Caruso to sing like Maria Callas. They don’t stop recording and tell everyone to stop playing Verdi because they prefer Bach.

“I think many entrants to wine wish to impose their own tastes and ideas on a site. I have quite catholic tastes and enjoy the differences in every region. So it’s the other way around: let the site express itself.”

He says that from the outset, they have always stuck to a simple mantra: “Excellent vineyard work, a sensible harvest time with ripe grapes, and careful hands-off vinification. We didn’t want to make compensations with the wines or the vineyards. We wanted it to be what it would be. And just be content that that might not be very good,” adding that having excellent grapes is half the battle.

“For me, it’s like fishing,” he continues. “You put your line in the ocean and you see what comes up. You do the best you can with the preparation and the work, then what happens is not in your control. We didn’t ask for a guarantee or complete control over what might result, and the wines might have been ungainly or of no great interest. We weren’t trying to censor unique things about the site in what we did. In fact, that phrase ‘censoring the site’ captures for me what is the biggest mistake.”

The estate now comprises 15.5 hectares, of which around four hectares are planted with white varieties, including Clairette, while additional Syrah has also been added.

While it’s easy to be wise with hindsight, Dougan says they did make mistakes in the beginning.

“We pruned the vines so there was open canopies with exposure to sunlight and air, and that probably works wonderfully well in a cooler climate with more rainfall, but in the south of France, it may not have been the best idea — the grapes appreciate a canopy to protect them from the sun. However, the inaugural vintage [in 2005] was fortunately wonderful, quite a warm year, producing rich, opulent structured wines, but at the same time with a lift and energy to it.”

Live and learn

Robert Dougan has been able to introduce a number of new varieties to the vineyards including Clairette

But mistakes can be regarded as learning opportunities, and Dougan says they have made big changes in the vineyards since the early days, with an increased focus on white wine production. Initially, the domaine was planted exclusively with red grapes until Dougan stumbled across two rows of Viognier and Roussanne in a vineyard that was originally thought to be Syrah. As a result, Dougan decided to make two barrels of a second white wine, Deusyls de la Pèira, which was very well received by critic Jancis Robinson MW who compared it to a Northern Rhône white.

Another serendipitous discovery led to the planting of the Clairette grape when it was found that France’s earliest known winery had been discovered near La Pèira. Dating back to 10 AD, archaeological seeds from the site revealed them to be Clairette, identical to varieties grown today. “So we had to plant Clairette,” says Dougan, alongside Roussanne, Marsanne and Grenache Blanc.”

Annual yields at La Pèira are small — Dougan likens them to “Yquem-like levels”, with the first vintage producing around nine hl per ha, with today's typical yields being closer to 15 – 20 hl per ha. This equates to around 500 cases of the grand vin La Pèira and 700 cases of the second vin each year, as well as 1800 cases of Obriers de la Pèira, 300 cases of Deusyls Blanc and 110 of Matissa.

“From a business point of view, that [such small yields] was seen as suicidal. So the amounts of wine we make are incredibly small, and really, that can only work if the site is excellent, which you don’t know until much later. So that was part of the discovery.”

Nonetheless, the estate exports much of its production, initially to the US, when around half of the total crop was earmarked for the American market. Slowly, the UK, Europe and Asia became more important overseas destinations, though Dougan says that they often hold off working with a country until they have a certain importer lined up to team up with. “One company in Switzerland we only worked with a decade after first approaching and held off until then.”

Right partner

Robert Dougan was so keen to work with Corney & Barrow in the UK that he turned down other opportunities to wait for the right time to join one of the UK's most respected wine importers

The UK, as one of the oldest and most important wine markets, was a key destination for La Pèira, but Dougan says he was so keen to collaborate with Corney & Barrow that they held off for several years before selling into the UK — prepared to wait until a deal could be concluded with the prestigious wine distributor and importer.

“I think we first approached Corney & Barrow a full 12 years ago just after we started,” he says, which he admits was probably a “bit premature”.

“They have an incredible portfolio of exclusive wines from Petrus to Romanée Conti and the heritage of being one of Britain’s oldest wine merchants, but what really stood out with the release of the wines is the care and attention to every detail.”

La Pèira has just converted to organic production, though from the outset, all the vineyard work, from winter pruning to the harvest itself, has been done by hand.

“We have so little of the 2021 vintage we plan to bottle by hand in the old pre-industrial way with La Chèvre à Deux Becs,” he says, “I wouldn’t want to chalk it up to sustainability, nor to advise it, but with the smaller vineyard such as the Bois de Pauliau, we’ve tried this year to start an experiment by working those two hectares in exactly the way it would have been in the pre-industrial era.”

Dougan believes it’s important to take a balanced approach to organic farming, pointing out that many producers still work with la lutte raisonnée (literally, the reasoned struggle or supervised control) and are not organic.

“If that means they only use treatments that are not organic to keep a vineyard alive, then I don’t think they should be derided,” he says. “The reason we went organic was it left no grey area and made our working processes clear for us and everyone.”

Dougan reports that winter pruning has just finished at La Pèira, and the vineyards have benefited from some good rain recently, which, along with the winter rain, has replenished the water levels.

Onwards and upwards

As to the future, Dougan believes the outlook for wine from the Languedoc — or the Occitan as he prefers to call it — are rosy, thanks in part to changing perceptions of the region.

“I think that that south of France is almost like London and Paris’ California. It’s about 120 minutes away, which is a similar distance from San Francisco to the winelands in California. But the UK is slowly waking up to the fact that the world’s biggest wine region is on our doorstep, and it has every type of aspect and soils. You can go from the shores of the Med to high-altitude vineyards, so there are all sorts of discoveries to be made.”

Robert Dougan in his other mode - as a successful song writer, film composer and musician

Meanwhile, there is not just wine to be made, but music too, with Dougan continuing to write and produce. He has just released a cover of the song Beautiful Things, originally recorded by Anthony Newley, as well as working on an album release of Furious Angels (Revisited) recorded at Abbey Road Studio and featuring over 100 string, woodwind and brass players.

He draws close parallels between music and wine, not only in the funding of his own recordings (“which with orchestras is ruinous, and a very good taste of what a wine estate was going to be like”), but also the similarities between the vineyard, terroir and vintage being the authors of the piece, and the vineyard work and harvest that of the accompanist.

“The wine estate’s true task is to be like a sound recordist and to record all with high-fidelity,” he says, conceding in self-deprecating fashion that his metaphor may be “slightly mixed”.

* You can read more about La Pèira here.

* Its wines are distributed in the UK through Corney & Barrow - a commercial partner of The Buyer.