“Beaujolais is wine made by wine lovers for wine lovers, not for investors, that’s why they’re different from Bordeaux and Burgundy,” pronounced Dutch journalist Ronald de Groot as we sat around a dinner table in the pretty village of Romanèche-Thorins at the heart of the Moulin-à-Vent region last March.

Dawning of a new age in Moulin-à-Vent

Amen to that. While the Beaujolais Nouveau campaign of the 1980s and 1990s was incredibly successful in that sales and production went through the roof, it had a catastrophic effect on the region’s reputation for serious, quality wines.

The change since then has been dramatic, with Beaujolais Nouveau and other low-quality iterations fading into the background as accomplished winemakers have worked hard to change perceptions of their wines. Nowhere has this been more successful than in Moulin-à-Vent, where land prices are rising as its potential to produce top-drawer wines is being noted by beady eyes.

Of the 10 crus that represent the best of Beaujolais, Moulin-à-Vent is historically the most highly regarded. At the turn of the 20th century, it was already well known for the quality of its wines - André Jullien, the early-19th century wine writer and cataloguer of wine regions, considered it to be on a par with Vosne-Romanée, and in 1869 it was recognised by engineer Antoine Budker, who painstakingly mapped the vineyards and unofficially ranked their individual lieux-dits according to the quality of their terroirs, rather than merely by the price of their wines as Bordeaux’s more famous 1855 classification had done.

No self-respecting restaurant, brasserie or palace would have been without Moulin-à-Vents on their lists, often at prices that exceeded grand cru Burgundy wines. However, wine fraud was rife at the time, exacerbated by the effects of phylloxera on the French wine industry at large, which prompted Moulin-à-Vent’s growers to lobby for appellation status. This was granted in April 1924, making it France’s third oldest (after Mercurey and Châteauneuf-du-Pape), a full 12 years before Beaujolais as a region became a designated AOC with its simple three-tier classification – Beaujolais, Beaujolais-Villages, and the various crus.

30% of Moulin-à-Vent's vineyards could be granted premier cru status

Premier cru Moulin-à-Vent

I was among a group of wine professionals - producers, academics, journalists, local dignitaries - gathered not only to celebrate this 100th anniversary, but also to mark Moulin-à-Vent’s application to grant premier cru status to the best 14 of their 71 lieux-dits sites, amounting to around 30% of the cru’s total 640 hectares.

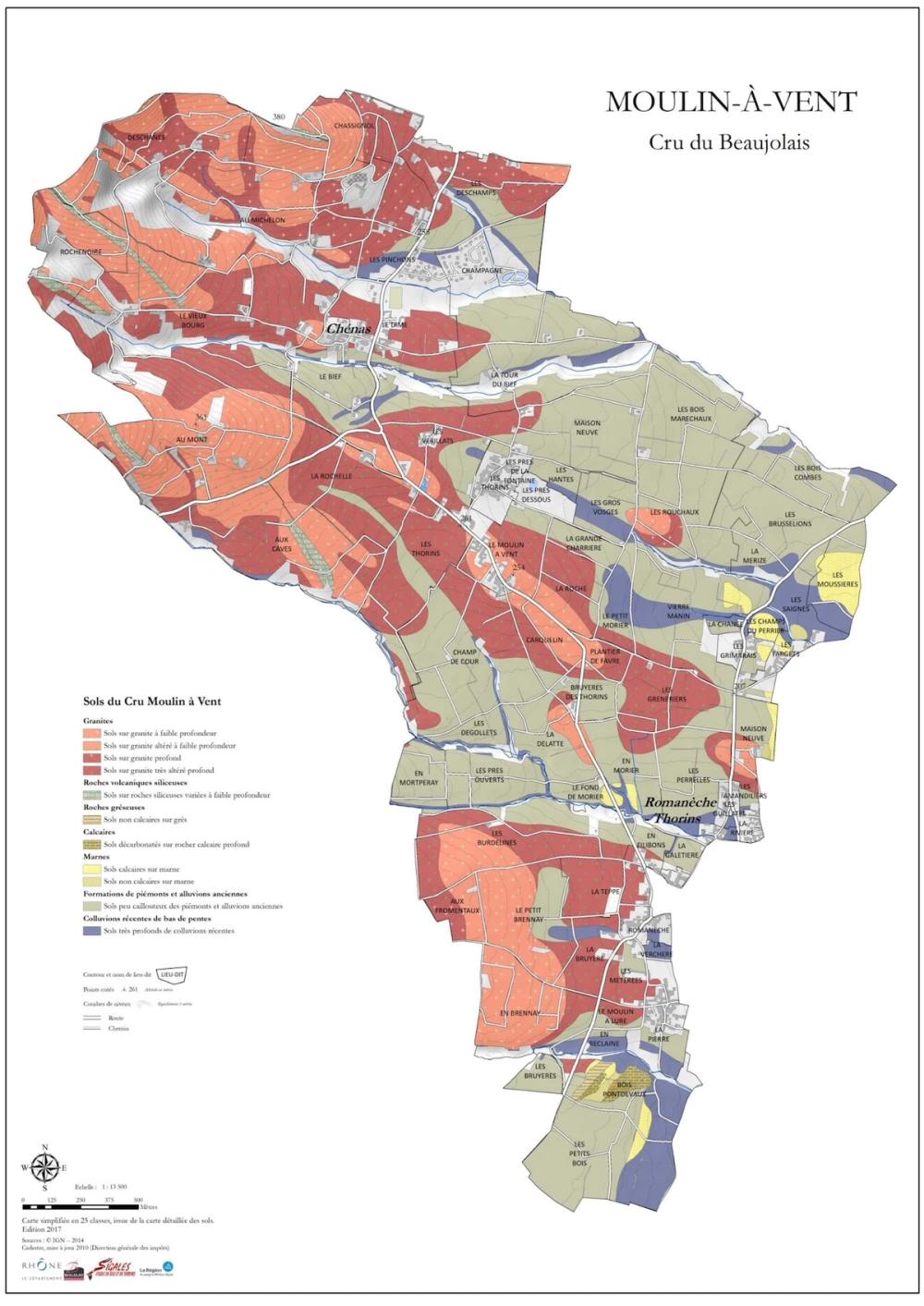

This follows an exhaustive analysis of their soils that was published in 2009 (and which bears a striking resemblance to Budkar’s findings in 1869), and rigorous quality assessment during two years of blind tastings from each site.

Most of these lieux-dits are south-facing slopes on the pink granite for which the region is famous, rich in minerals and giving wines with a distinctive nervy tension, although some are on the ancient alluvial soils in the east which tend to result in more opulent, weighty wines.

In addition to criteria such as historic and contemporary reputation, the proposed new premier crus will be subject to rules including banning the use of pesticides, a maximum yield of 50 hectolitres per hectare, and at least six months’ maturation before release, which must not be before December in the year following the vintage.

Tasting some older vintages during the 100 year celebrations

Although there is still some semi-carbonic maceration used in Moulin-à-Vents, there is a wide diversity of winemaking styles these days and producers will be allowed to use whichever vinification methods they choose.

Around 100 producers are involved in this application process, also showing wide diversity. They include noble, well-established estates such as Château des Jacques (also celebrating its centenary this year; now owned by Maison Jadot and known for its rich, age-worthy wines; see focus here) and Château du Moulin-à-Vent (dating from 1911, bought in 2009 by the Parinet family and now run by son Edouard with a very modern touch).

Tipped to be a future superstar: Elisa Guerin of Famille Guerin

Smaller outfits, lower intervention

Then there are smaller, more modest operations, often run by a young generation who have taken over and updated their family domaines, often embracing the region’s recent reputation for low-intervention techniques that appeal to the modern drinker.

Famille Guerin is one example, an estate now in the very capable hands of Elisa Guerin, aged 32 and tipped by many to be a future superstar of the region.

“Ours is the classic story of French agriculture,” she told me. Her grandparents were growers who’d owned no vineyards but gradually accumulated land, and in the 1970s built a small cellar of concrete tanks alongside barriques and old foudres.

“The best Beaujolais does not have too much oak,” she remarked.

Elisa took over the domaine in 2019 having trained as an agronomist and since then has moved away from her father’s traditional style to make around 3000 bottles a year of focused, precise wines using organic viticulture, spontaneous fermentation and no added sulphur apart from just a little at bottling.

In the vineyard, from 2022, she added algae and plant extracts to the copper sulphur treatments. “It really helped the grapes and the photosynthesis of the leaves,” she says. “But while some biodynamic practices seem to work, I’m not romantic about it.”

Rather, Elisa takes a forensic approach to her winemaking, spending a lot of time at the microscope to keep check on her fermentations, and is somewhat frustrated by some ‘natural’ winemakers in the region who often buy in grapes which are often not even organic, let alone biodynamic. “They just leave them to ferment and go to the bar to drink beer. Their faulty wines are not intellectually interesting to me.”

“And it’s hard to make your own space as a woman here,” she goes on. “We have to be twice as good as the men in order to be treated as their equals. There are many big personalities here; many big egos. It’s getting better with the younger generation, but then I get accused of not being ‘natural’ enough because my wines are so clear and not at all funky,” she adds with a sigh.

That said, Guerin is the President of Bien Boire Beaujolais, an umbrella organisation for six associations together representing over 225 winemakers working together to promote the region and to support each other with shared know-how.

“Now we make wine here in so many different styles. It’s important for us all to show to the global wine scene that we have various and complex terroirs, and that Gamay can be really multi-faceted,” says Guerin, who is working on the premier cru application project with her father. She has 1.5 hectares of 70-year-old vines in the heart of the Les Thorins lieu-dit, which she’s confident will be assigned premier cru status when they are announced.

“It will be a great recognition of the fantastic terroir we have in Moulin-à-Vent, but we have to be patient and have the consensus of the winemakers in order for it to succeed. For me, it cannot be done with the classic industrial models; we need to focus on the environmental aspects of our viticulture as well as the quality of our wines.”

Premier cru status is not expected to be granted before 2030. If, as seems likely, it is, it will raise the reputation of Moulin-à-Vent’s wines to put them, a century later, once again on a rightful par with those from Burgundy. Their prices will probably rise correspondingly; perhaps this is the time to invest in these wines as well as to love them.