Three things inspired Andrew Quady to start making Vermouth: a lecture from the 1970s that he still had the notes from, a Martini in Marseille and a challenge from a friend.

What’s your favourite firework and why?

There were a couple of items I developed: one was an underwater flare. Another a mortar round which had a rocket attachment affording extra height and distance. This device was used as a countermeasure against heat seeking or radar target guided missiles.

Can you describe how you first got into making wine? Fireworks to wine doesn’t sound like a natural progression

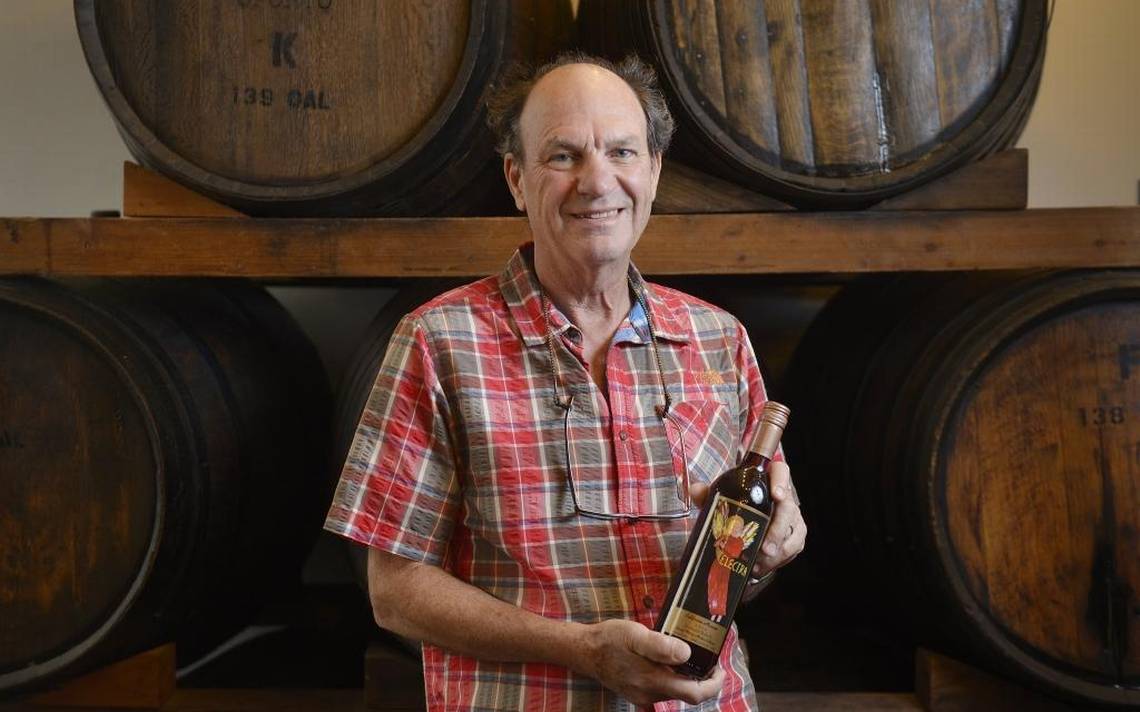

Andrew Quady, The Dorchester, London

Late in 1970 there was a mishap at the pyrotechnics factory where I had been working and the management of the controlling company decided not to reopen the plant. Everyone was laid off which meant that I would receive unemployment benefits. With the support of my spouse, Laurel, we decided to use this opportunity to retool myself for a career in California’s developing wine industry.

Laurel, meanwhile, took the opportunity to take accounting classes. By mid-1973, I had received a master’s degree in food science/oenology specialisation and landed a job at a winery in Lodi. Laurel was finishing up her classes and a year or so later passed the CPA exam.

In 1975 at the request of a colleague in the retail end of the wine business I made a batch of port style wine from an old Zinfandel vineyard at one of the wineries in Lodi, as a moonlighting project.

We relocated to Madera California in 1976 as I took a job at the facility which is now part of Constellation Brands (called Heublein Wines in those days). My California port was ageing at a friend’s winery in Napa Valley. The next year we purchased a home and land with an easy commute to Heublein Wines. The property we purchased had already been permitted by the US alcohol authorities (BATF) as a commercial winery. We put up a small building, turned it into a winery and by September 1977 were making more California port, again while moonlighting from our day jobs.

Laurel and Andrew Quady

By 1980 my port production had exceeded my sales to the extent that we couldn’t fit any more port into the winery building and didn’t need to purchase grapes that year. However, the Madera County farm advisor advised me of an opportunity with a vineyard of an unusual Muscat variety: “Orange Muscat” and wondered if I might be interested in this heretofore unknown (to most people) variety.

As it turned out, we were considering a line extension along the lines of a sweet fortified white. I was somewhat familiar with the variety. UC Davis had a few Orange Muscat vines in its variety collection. Partly because of the opportunity to work with a virtually unknown varietal, we decided to turn these grapes into a new sort of sweet white using a combination of skin contact, barrel ageing, and fortification (Beaumes de Venise meets Sauternes).

We introduced the new wine in 1981 with the name Essensia (refers to our skin contact technique which extracts the ‘essence’ of the grape), and an exciting modern ‘art’ label. Initial demand was very strong and it appeared that this new wine had ‘legs’.

Later that year, Heublein Wines told me that they no longer needed my services. In the meantime, after working for two different CPA companies, Laurel had launched her own CPA practice in Madera and was doing well enough that we could live off what she made, allowing me to spend my time with the Quady Winery business, and importantly to be able to reinvest all our profit, allowing the winery to grow.

Was the transition easy?

Quady: “Entering wine at a young age was a distinct advantage”

Compared to lots of people who were getting into the wine business in the 1970s I had the advantage of starting young in life and after two years at UC Davis knew quite a bit about how wine is made. The Davis programme was known for giving students the big picture. Maynard Amerine, head of the department taught the class: introduction to sensory analysis of wine, which helped young winemakers communicate with other professionals using a common language.

The wines to be analysed were selected such that by the end of the course the students would be familiar with the most famous types of wines produced around the world, what they should taste like, the grape varieties used, the effect of environment (climate and soil), processing and ageing. It was a masterclass on wine combined with a class on sensory analysis.

Davis California is a town close to Sacramento and an hour plus drive to San Francisco and the Napa Valley. It is a very attractive agriculturally based part of California. After the pressure and safety issues involved in the pyrotechnics business, I appreciated the chance to devote my time to learning all I could about the technology of winemaking. Also, I chose Dr James Guymon as my thesis professor as Guymon was also a chemical engineer and we had that in common. My thesis involved interactions of wine and grape quality with the quality and composition of corresponding brandy distillates.

Compared to my job at the pyrotechnics company, in a dry, dusty suburb east of Los Angeles, life in Davis was heaven. And, I had the opportunity to make a fresh start in a new career of my choice.

Is there any part of both jobs that is the same?

The major factor in the decision to change careers involves the differences in the products and their uses: Pyrotechnics versus wine. They both involve chemistry. My former job was focused on military uses (although we did have some contracts for display fireworks).

Modern wineries use a lot of equipment and the fundamental engineering knowledge that was part of my chemical engineering training was especially handy when I was working for Heublein Wines. The cross training in both engineering and winemaking gave me unique insight into opportunities to improve profitability in the process development area. Also, my own winery, started in 1977 in Madera on a shoestring budget and had mostly old used equipment.

Quady Winery

With the help of some friends, a bare bones building was turned into a working winery in a few months. I installed 3 phase electricity to power the used pumps and crusher, lighting, air conditioning. Even the air conditioner was used equipment. I used my understanding of statics to design a support system for the tanks we purchased.

Having worked for several different companies before starting my own, and having taken some accounting classes myself, I was familiar with financial tools, and different management styles. Now that we run a much larger company, close to 25 employees, personnel issues are increasingly important. Much of our success relates to key employees and their loyalty.

Our head winemaker, Michael Blaylock, retired this year after 33 years. Joining us after graduating from Fresno State’s oenology program, we were his first and only employer. Mike gradually took over the winemaking and winemaking record compliance program from me and produced one after another of consistently made award-winning wines. This left me free to work on other areas of our business, mainly budgeting and sales.

Did you always set out to make fortified wines and why was that?

Having a job in California’s central valley, first in Lodi and finally in Madera, I recognised that even though the markets were smaller for fortified and sweet wines, if one wanted to make world class wines, a strategy involving fortified and sweet wines made sense. Also, in making that first California port for a colleague in the retail end of the business, I had started down this road. When we came out with Essensia, the die was cast.

Do you consider yourself first a dessert wine producer or a Vermouth producer?

We are first a sweet wine, actually Moscato, producer. Low effervescence Moscato (4.5 to 7.5% alcohol) which is in the table wine tax category, amounts to around 90% of our production. The Vermouth business has increased such that it amounts to about 6% of our production today. Our traditional fortified wines, Essensia, Elysium, and Starboard (our name for California port) make up the remainder.

Are the two compatible in terms of production?

We use the same grape varieties for the lower alcohol Moscato range and the traditional fortifieds, Essensia and Elysium. Essensia is also used as a component in Vya Vermouth, especially Vya Sweet which is largely Orange Muscat.

How do you manage the two categories? Are they totally separate or is there crossover?

The full Quady range at the winery

From a production standpoint, Vermouth is a wine and must be made in a winery. A distilled spirits operation cannot produce Vermouth. The unusual thing about Vermouth is that it is made according to a secret formula and process. This is unusual in the wine industry but very common in the world of aperitif wines.

From a marketing standpoint, we deal with different markets for the different wines, depending on the market. We adjust our focus accordingly. In the US which is about 90% of our business, the low alcohol Moscatos are primarily sold in retail stores and the consumers use these wines as table wines, consumed with the meal or as an aperitif or entertainment wine, like a cocktail.

Moscato (basically any wine made from a Muscat variety) is the number 4 most popular wine in the US. This is a very large market. The number 1 imported wine into the US is a line of mostly Moscato from Italy called Stella. Last year Stella sold 1.3 million cases. We compete in that area with domestic Moscatos and are especially strong in the sweet red Moscato category where we use Muscat Hamburg grapes, the same ones which go into Elysium.

Vermouth is skewed toward restaurants and cocktail bars. The retail customers are cocktail aficionados. This has been a growing market and we compete with the higher end Italian Vermouths. Essensia and Elysium are split between restaurants and retail.

In our export markets, the UK, S. Korea, Taiwan, the Netherlands, Japan, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany, things are different in each country. The UK, Netherlands, Sweden, Japan, Canada and Germany take mostly Essensia and Elysium. The UK takes the most Vermouth. Denmark takes mostly Starboard. Taiwan and S. Korea take only Moscato.

What did you set out to achieve with your Vermouths?

I wanted Vya to be known as an aperitif wine which is delicious on its own, and I think we have achieved that. Actually the best Vya cocktail is the mixture of Vya Sweet and Extra dry, around half and half. Of course the manhattans, negronis, and martinis are just amazing but that wasn’t the original goal. Vya Whisper dry was made primarily as a delicate dry white vermouth delicious on its own.

What inspired you?

There were three events: first, an amazing seminar on Vermouth given by Amerine in 1972. I kept all the notes. Secondly, following my graduation in 1973, Laurel and I spent six weeks in France and Germany soaking up the European culture. We still remember how good a glass of Martini and Rossi Rosso Vermouth tasted in a bar on the wharf in Marseille. Especially since the bar served complementary steamed mussels with each drink order! Third, after a colleague in the restaurant business in California was complaining about his customers not appreciating Vermouth because they were drinking mainly martinis with no Vermouth in them, and he suggested that I try my hand at making a better Vermouth, I dug out those notes from Amerine’s class and started in. It took two years and Vya was born.

Did you consult with mixologists/ bartenders to see what they were after?

No

Talk us through your range and how they can be used by the on-trade

Quady making an aperitif at the Dorchester

We produce two different dry white Vermouths: Whisper Dry and Extra Dry. Whisper has a more delicate touch of botanicals and the botanicals selected impart principally aromatics. We use a very nice but neutral dry white wine for the base wine in Whisper. The result is a drink which smells like botanicals but except for the alcohol being around 17%, tastes like a fresh but nondescript dry white. Sort of a Pinot Giglio style with more mouthfeel and some interesting aromatics.

Our second dry white Vermouth, Extra Dry, has a nice proportion of botanicals which impart flavour as well as aroma. Extra Dry has a significant mouthfeel and a very long aftertaste. It is also good on its own but we think it makes a fantastic wet martini, mixed around 50% with gin.

Our sweet Vermouth is in the style of classic rosso in that it is built on bitterness offset with sweet. On first sip one notices sweet but this quickly changes to bitterness with lasts a long time until you take another sip and then notice the sweet again. The aromatics skew towards culinary baking spices, cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, ginger, cardamom. Since American whiskey gets a vanilla taste from oak age, the other spices in Vya add components which give the drink a certain holiday spice dimension. Vya sweet is the top seller for us.

What makes them different to other Vermouths on the market?

This is a complicated question because there is no homogeneity to the other Vermouths on the market. They are all different.

In dry white Vermouth, looking at the classics, Martini & Rossi and Noilly Pratt, one has a sort of artificial one-dimensional flavour and the other more complex but oxidised. We use a nice fresh, dry white as a base wine. So this is the background taste we begin with. In the area of sweet Vermouth, we use Cinchona bark as the main bittering agent which I believe is common in Sweet Vermouth from Italy.

We do not use wormwood but it is not clear if wormwood, which is a nauseating and very bitter plant and only used in Europe because it is legally required as a traditional ingredient, is present in sufficient levels as to make much difference in the taste. Different Vermouth makers have different ideas about aromatics. Carpano Antigua is very high in vanilla flavour. Martini & Rossi is very high in oregano. Vya Sweet shows cinnamon, ginger, clove, nutmeg, etc.

Where do we go from here Vermouth-wise?

Mixologists are always on the hunt for something different and better but the market would really open-up if people started appreciating Vermouth as a delicious aperitif on its own.