“Biodiversity is not simply a nice-to-have, it is a fundamental component of a healthy, sustainable and profitable vineyard – even if it seems today to be a complicated achievement,” writes Bernheim from the 2nd Vignoble & Biodiversité conference.

Châteauneuf’s ‘marathon of hedgerows’, a 42km planting, was of particular note at the Vignoble and Biodiversité conference

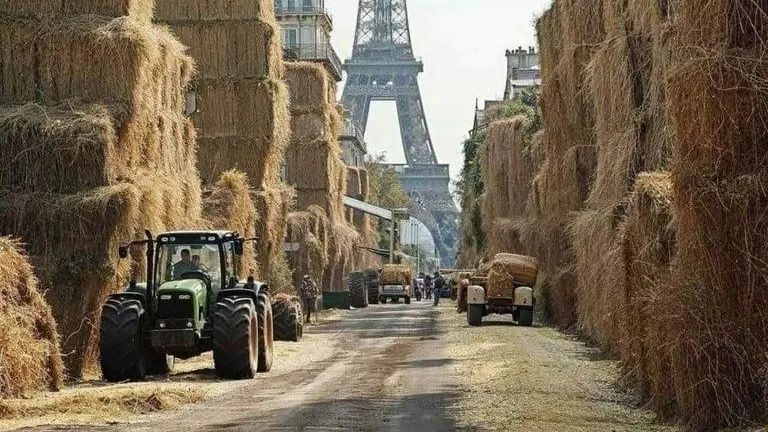

Vineyards in France make up only 3% of the country’s agricultural area but contribute a disproportionate 20% of the country’s pesticide usage – a fact especially relevant today, after weeks of farmers’ protests have led to government concessions on the regulations surrounding pesticides, and a major step back for biodiversity.

The second edition of Avignon’s Vignoble & Biodiversité conference was held this January, bringing together speakers from across Europe to discuss the state and future of biodiversity in the vineyard. The conference was organised once again by Birte Jantzen, and co-hosted by Châteauneuf-du-Pape AOC, keen to highlight the measures they are taking to introduce biodiversity into vineyards suffering from increasingly hot and dry summers.

Agronomist Alain Canet stresses the need for humid air in vineyards and how trees can help

Hedging our bets

Of particular note is Châteauneuf’s ‘marathon of hedgerows’, a 42km planting of local trees and bushes along parcels, designed to provide shelter for wildlife and break up the uninterrupted ‘sea of vines’. As vineyard parcel sizes have consistently increased over the last half century, this is more important than ever. Such practices, although simple, have impacts that reach far further than simply helping biodiversity, with trees contributing to significant decreases in soil temperatures, helping to mitigate climate change, as well as turning the soil into a carbon sink and increasing its biomass.

Speaker Alain Canet, an agronomist, in his talk on the primordial role of trees in returning humidity from the ground to the air claimed that vineyards are better able to withstand extreme heat from climate change if the air is not overly dry, a feeling echoed by many winemakers, such as Victor Schoenfeld at Golan Heights Winery, who (although not present at the conference) confirmed “we don’t really discuss temperature […] so we look at Vapor Pressure Deficit, which is much more useful”.

One attendee at the conference was more pragmatic, arguing that “[the term] agroforestry overstates what is really just a few trees”. This feeling was echoed by one Châteauneuf producer for whom the cheapest way of encouraging biodiversity was to “simply stop cutting down trees on the edge of parcels” – although the significant labour costs that trees around or amongst the vines require to prune and maintain them at appropriate heights and sizes was also mentioned. The shape of the hedges themselves requires thought, as curved hedges have a greater perimeter-to-area ratio than straight lines, encouraging a different range of species.

Layout of vineyards

Layout of vineyards is important:

- Contour-planted vineyards (where the rows of vines follow the contour of the hill, rather than going up and down or staying straight, minimising erosion from heavy rains)

- Keylines (rows that are slightly angled to channel water towards the driest part of the parcel)

- Swales (ditches and mounds, designed to capture rainwater runoff) and

- Seasonal ponds were all mooted as helpful for biodiversity.

They provide year-long or seasonal habitats for a range of species, as well as proving essential for water conservation and management in increasingly dry vineyards – measures that favour biodiversity also facilitate viticulture and good grapes.

Oidium (powdery mildew) is significantly less common in vineyards with high levels of trichoderma fungi in the soil

Smaller organisms and scientific rigour

Although trees and hedges are the most visible contributor to a vineyard’s biodiversity, smaller organisms were also discussed, their disproportionate impact on viticulture all too easy to overlook.

Soil fungal health is seen as one of the most promising subjects, with the diversity and biomass of fungi playing a colossal role in vines’ ability to uptake nutrients and water. Professor Marc-André Selosse from the MNHN Institute of Systematics, Evolution and Biodiversity discussed a study which found oidium (powdery mildew) to be significantly less common in vineyards with high levels of trichoderma fungi in the soil – a tangible promise for many viticulturalists.

The need for scientific rigour was a recurring theme, with one of the speakers, Dr Joana Döring, presenting the findings of an 18-year data-driven ongoing study at Geisenheim University. Trialling conventional, organic and biodynamic practices on four identical plots of Riesling led to striking conclusions. Berry size, cluster size, and canopy size were all significantly reduced in the organic and biodynamic parcels. Although the study was exclusively concerned with the viticultural side, the consequences on the resulting wine, its quality and aromatic profile are easy to imagine.

Jean-Francois Agut: implementing biodiversity-friendly practices in a grain-and-wine farm in Gers

Mitigating the cost

For many winemakers, the question is: is the cost of encouraging biodiversity worth it? These questions can be easier to answer by looking at secondary income sources for wineries, especially oenotourism.

Wine tourism and the use of vineyards as venues for events and celebrations, for many a fast-growing segment of the business, depends on Instagram-friendly vistas and vineyards.

Trees in blossom, animals in the vines, birds, and groundcover all contribute to a vineyard’s beauty, an essential part of the modern business model, according to the first speaker, Régis Ambroise, in his talk about a ‘post-petrol viticulture’.

Opinion was split on the importance of other biodiversity-related sources of income, specifically those derived from secondary crops or from livestock in the vineyard. Fruit trees in particular are widely considered to be too much work to even harvest, interspersed as they are with significantly higher value-added vines – as Édouard Brunier of Domaine du Vieux Télégraphe succinctly put it “if you want 70ha to be managed by two people on tractors, it’s just not possible […] and we don’t want to climb a 20m ladder to prune a tree if the mistral is blowing”.

A far cry from the high prices commanded in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Jean-Francois Agut presented a case study of his mixed grain-and-wine farm in the Gers, describing the steps towards a successful implementation of biodiversity-friendly practices, even for relatively low-value, high-yielding IGP Chardonnay, especially his use of native ‘weeds’ as groundcover in order to reduce costs and minimise tractor passages in the vineyard.

A pragmatic approach

The conference was ruled by pragmatism and an awareness of the practical challenges that need to be addressed, for example the legal and regulatory hassles associated with livestock in the vineyard. Regulations designed to limit the spread of bird and swine flu between wild and domesticated populations impose stringent fencing requirements on any vineyard in which either chickens or pigs might be allowed to roam.

Legal agreements, especially concerning liabilities, must also be drawn up between vineyard owners and livestock owners, adding on costly legal fees. The CEREL project in the Loire valley was brought up as an example to wineries: amongst other things, it provides template legal documents to allow for partnerships between grain growers and livestock breeders. A similar framework for collaboration does not exist for wineries, requiring legal agreements to be rewritten from scratch for every vineyard.

The conclusion was clear: biodiversity is not simply a nice-to-have, it is a fundamental component of a healthy, sustainable and profitable vineyard – even if it seems today to be a complicated achievement.

Ben Bernheim has lived in the south of France since 2002, involved with wine through working in vineyards, as a sommelier, and writing, tasting, and learning full-time since 2020, primarily about rosé, the wines of the south of France and the western Mediterranean. He builds interactive vineyard maps on pink.wine and is always happy to talk about interesting wines at ben@pink.wine.