The Meandering Valleys of Rioja Alta

Rioja is undoubtedly one of the world’s most famous wine regions. That fame, however, can be a double-edged sword. People think they know Rioja, in the same way they know Bordeaux, or they know Burgundy, or they know Napa. They have two or three lines in their head about where it is, a couple of producers they know and the well-known wine styles that have made Rioja’s fortunes over the past hundred years or so.

Rioja does still possess large and well-known producers providing the world with the brands and labels they’ve known and loved for years. A gentle scratch of the surface, however, reveals so much more to captivate wine lovers looking for that point of difference. Today’s Rioja is a patchwork of diverse terroirs, ideas, and modern approaches to the increasingly understood landscapes, climate and grape varieties.

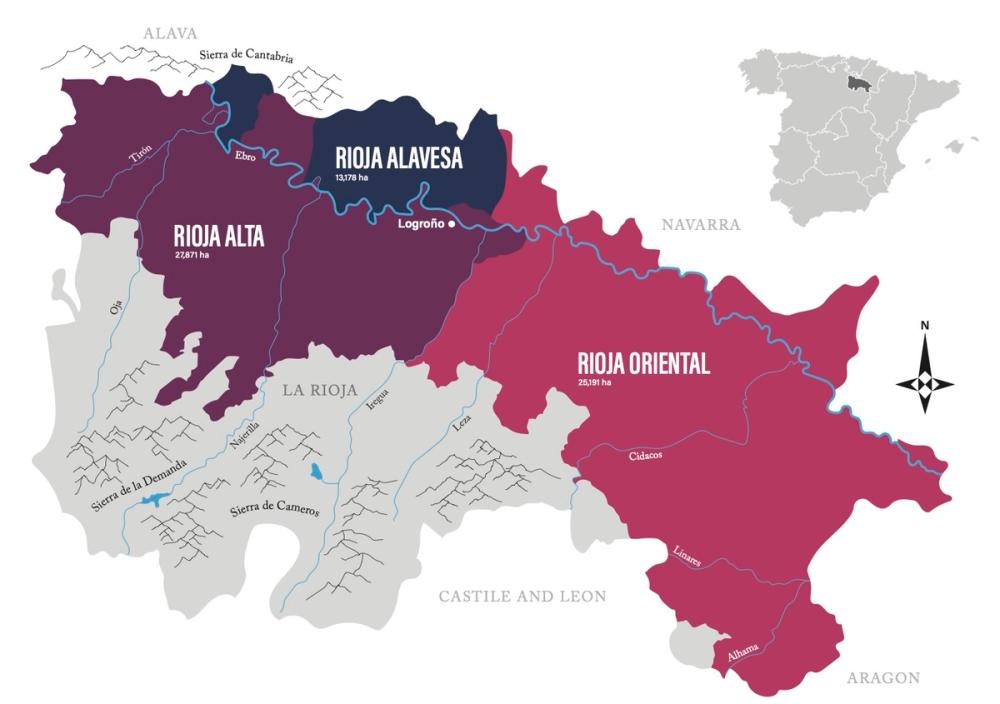

In this forthcoming series of articles, I’ll be looking in depth at the three official zones of Rioja. Yes, we’re going to need to talk about mountains, rivers, soils, and grapes. Yes, there are probably sections where we’ll repeat various aspects. But go with it. Understanding these concepts and understanding the diversity of terroir in each of these zones goes a long way to understanding why Rioja is keenly referred to as the “Land of 1,000 Wines”.

So, let’s start at the start with the largest of the three zones by area planted; Rioja Alta.

Where Is Rioja Alta?

The spread of Rioja Alta is very easy to explain. Nearly. It covers all the region of Rioja to the west of the regional capital of Logroño and the Rio Iregua, and to the south of the Rio Ebro as it snakes its way from the North-West to the South-East and out towards the Mediterranean. As I mentioned, it’s nearly very easy to explain. It’s important to remember that Alta also includes a very important section north of the Ebro, splitting the northern region of Rioja Alavesa, known as the Central Sonsierra district.

It’s the largest of the three zones, covering around 28,000 hectares of Rioja’s 66,000 in total, and is based (almost) entirely in the autonomous political commune of La Rioja. The climate is often generalised as continental with some maritime influences. Indeed, if we only look at the average measurements for each of the three zones, Alta is the wettest zone and relatively cool. So this much we know. As much as some generalisations are valid, as ever, the real situation contains many more nuances than that which we’ll have a look at now.

River Valleys Offer Huge Diversity

Najillera Valley

Of course, we associate Rioja with the dominating influence of the Rio Ebro whose 120km west to east stretch does so much to define the terroir of the region. One of the biggest effects of the river is to channel those warming, drying Mediterranean easterly winds deep into the heart of Rioja. By the time you get as far west as Rioja Alta, most of that effect has died down, but those vineyard sites closest to the river, especially those near to meanders and loops in the Ebro, benefit from those warming effects.

Adrián Martínez Bujanda is based at Finca Valpiedra who manage 80 hectares between Cenicero and Fuenmayor on the south bank of one such meander. “We launched our Petra de Valpiedra in 2016,” says Martínez Bujanda. “It is 100% Garnacha that ripens beautifully on our warmer sites.”

Most people who are asked about the rivers of Rioja will probably only know the name of the Rio Ebro. That’s fair enough. It’s the biggest. It defines so much politically, geographically and climatically. But to the south of the Ebro are a series of tributaries that make a huge difference on vineyard sites in Rioja Alta.

To the west lie the Rio Tiron and the Rio Oja, which flow south to north and into the Ebro at the town of Haro. Those keen eyed amongst you will have spotted one of the theories on why the region of Rioja is so named.

Eduardo Hernáiz of Finca La Emperatriz in the cooler, western municipality of Baños de Rioja, needs little convincing of the origins of the region. “It’s the origin of Rioja,” explains Hernáiz. “You see so many aiming for cool climate these days, we are the original cool climate area.”

The Rio Oja flows just a few hundred metres from the winery itself, as it rises to the South, so too the surrounding areas. “We’re only 15km south of Haro,” adds Hernáiz, “but we have nearly no Mediterranean influence anymore. We’re at 600m above sea level, the River at Haro is 400m. It’s cool, it’s Atlantic, and the elegance really shows through into the wines.”

The next major river, as you travel east, is the Rio Najerilla. This flows down from the usually snow-capped Sierra de la Demanda, and cuts an impressive valley as it does, with complex and diverse soils, slopes and aspects. So distinct and diverse is this valley, that many Rioja commentators talk about it as almost a separate region of its own.

It’s in these valleys that Juan Carlos Sancha, the fabulously expressive research professor of oenology at Rioja University, has set up his very own Bodega in Baños de Río Tobía. He has worked tirelessly to reverse the trend of the diminishing numbers of commercial varietals in Rioja. “In 1912 we had 44 varietals,” explains Sancha. “By 2000 we were at seven. The diversity of slopes and aspects in Najerilla allow me to replant and re-establish that forgotten history.”

Finally in Rioja Alta is the Rio Iregua. As much as we talk about everything to the west of Logroño is Rioja Alta, it’s this river that forms the basis for most of that border. As it weaves its way into Logroño it cuts a fertile path for all kinds of agriculture to be enjoyed on the plains.

But it fulfils a much bigger function for the vineyards immediately to the west. “The Iregua is undervalued for its effect on our climate,” says Hernáiz. “It’s the last line of protection, before Rioja Alta starts, that tempers the warm and dry Mediterranean influences of the east.”

Mountain ranges to protect and expose

Sanjazarra in Montes Obarenes

Rioja Alta is also defined by the mountain ranges that surround it. Not only do these provide a range of altitudes for grape growers, but also both protect and expose the vineyards to climatic pressures from the North, West and South in particular.

The range we always learn about with Rioja Alta is the southern mountain ranges of the Sierra de la Demanda and the Sierra Cameros. Part of the Sistema Ibérico, these are the mountain ranges that protects Rioja from the warm central plateau of Spain. It also rises steeply, fairly quickly, providing stark cooling altitude.

The higher reaches of the Najerilla Valley, for example, can reach well in excess of 700m. Juan Carlos Sancha’s Garnacha Peña al Gato translates as The Cat’s Rock, so named as the vineyard of 95-year-old Garnacha vines is so cold at 650m that even cats didn’t go up there.

These cooler sites, at altitude, are becoming increasingly viable due to climate change and are producing some of the most elegant red, white, and rosé wines across all of Rioja.

The other famous mountain range of Rioja, and one that isn’t always associated with Rioja Alta, is the Sierra de Cantabria to the north. It’s worth remembering, however, that a section of Rioja Alta does extend to the north of the Rio Ebro, from the town of San Vicente de la Sonsierra, and into these impressive mountains. With that comes the option of higher altitudes, south facing slopes, and diverse microclimates from sites protected from the cool Atlantic influence, and those exposed due to gaps in the range.

Another important mountain range is that of the Montes Obarenes. These mountains lie to the North-West of Rioja, providing altitude for those vineyards to the west of Haro, and also help to expose (rather than protect) this area to more of the Atlantic influences. It makes it one of the coolest and wettest part of Rioja.

Oscar Alegre of Alegre & Valgañón is based in Sajazarra in the far west of Rioja Alta, 580m up into the Montes Obarenes. “A geological map is much easier to understand than a political one,” says Alegre. “If you use Google satellite imagery, you can see the whiter soils and greener areas into the plateaus of Castilla, which so few people expect to see.”

Soil formations up and down the valleys

The soils up and down the river valleys of Rioja Alta are sandy and stony in nature and alluvial in origin.

When you’re trying to get a handle on the growing conditions across any wine region, you know that a chat about soils is only ever just round the corner. As you can probably guess by now, the soils of Rioja Alta are fairly diverse, but there are generalisations we can make to help us out.

The soils up and down the river valleys of Rioja Alta are sandy and stony in nature and alluvial in origin. These valleys are not as wide or flat as the Ebro Valley in Oriental to the east, meaning fewer large plots can be established. The stones and pebbles that allow for heat accumulation and radiation remain useful to ensure full ripening of the likes of Tempranillo and white varieties increasingly planted in areas previously deemed too cool for successful viticulture.

As the slopes rise to the sides of the valleys, and into the mountains to the south, the alluvial sands and stones give way to ferrous clay. These brownish-red coloured soils, similar to those in the river valleys in Rioja Alta to the west, are very evident with a quick look at satellite photos. These are deep soils of mostly compact rock formations producing grapes for medium bodied reds and rosés with great levels of balancing acidity.

The Sonsierra district, north of the Ebro, as well as the immediate southern banks of the Ebro around parts of Haro and Briones and out to the west, also contains some of the famous calcerous clay soils seen in many pockets of Rioja Alavesa. These soils can give great levels of minerality, tension and freshness in the wines, especially for those venturing into the growing numbers of top-class white wines from the likes of Viura and Garnacha Blanca.

One soil type, although not common but definitely worth a mention, are the Cantos. These are large, eroded white stones, similar in effectiveness to the famed Galets Roulées in Southern Rhône.

Finca Valpiedra’s vineyards on the Ebro’s southern banks make the most of their presence. “We’re lucky to have both the passing water, but also these stones to help regulate our temperatures,” says Martínez Bujanda. “We know having such low clay content is unusual for Rioja Alta, and it’s our job to let our wines reflect these unique soils. Trying our Finca Valpiedra Reserva against our Bodegas Bujanda Reserva (from Oyón in Alavesa) is something we love to compare. Same winemaker, same ageing, same blend, so you can really taste the soils.”

Grape varieties to watch in Rioja Alt

Old vine Tempranillo in Roda’s Perdigon Vineyard

Tempranillo is the main show in town in Rioja as a whole, and in Rioja Alta even more so. In the last 50 years it has increasingly dominated plantings, with now 88% of the vineyard space. In Rioja Alta it suits the cooler, higher sites and ripens well in the cooler clay soils. So cool are these sites that harvest can be up to two months between the first grapes harvested in the warm areas of Rioja Oriental and the cool areas of Alta.

The large plantings of Tempranillo, with some suggesting it is verging on a monoculture, is increasingly a cause for concern. Bryan MacRoberts of MacRoberts y Canals, a champion of protecting the 25% or so of Rioja vineyards over 40 years old, echoed a common thought that “the 1970s/80s industrialisation of the vineyards in favour of high yielding Tempranillo was as damaging to Rioja as phylloxera.”

Plantings are therefore increasing of other varieties, namely Garnacha Tinta for reds and Viura, Maturana Blanca and Garnacha Blanca for the whites as growers explore the cooler and higher altitude sites. The likes of Graciano or Mazuelo are garnering huge interest, especially in the face of climate change, but more so in Oriental.

Some proponents of increasing planting material have already begun to turn their backs on Tempranillo entirely.

Juan Carlos Sancha remains resolute: “I don’t believe Tempranillo is going to work in the face of climate change. There are about 570 wineries in Rioja, and I’m proud to say that I believe I’m the only one without any Tempranillo.”

In terms of the wines themselves, blends do remain more common. The backstory of Rioja was always to utilise the different properties of their grapes, with the tannins and acidity of Tempranillo or Graciano added to the body and fruit of Garnacha, or the deep colour of Maturana Tinta.

Rioja Alta, and especially the towns of Logroño and Haro, is home to both big brands as well as famous and classic-style producers. In the face of many now expecting Viñedos Singulares or Vinos de Municipio to showcase the idea of terroir across Rioja, these producers still feel Rioja-wide blends as the best way of showing off the best of what Rioja can achieve.

Guillermo de Aranzabal Agudo is the chief executive of La Rioja Alta, based in Haro. “Our key ingredient in continuing to satisfy our customers is show off what we consider to be the best of Rioja,” he says. “We still celebrate the differences between the zones, for example by buying our Garnacha in from Tudelilla in Oriental and our work in Alavesa with Torre de Oña. We know the differences and what they can add to blends. That provides the consistency that is key for our classic wines such as 890 and the 904.”

The larger producers, such as Campo Viejo and Faustino, base their operations here in the town of Logroño, closer to transport hubs and a labour force. These large producers still dominate, with the top 10 producers in Rioja commanding over 40% of the wine sales, meaning regional blending is vital for both consistency, style and critical mass.

A Visit to Rioja Alta

R. López de Heredia Viña Tondonia in Haro

Without trying to sound too much like the tourist board, I thought I’d finish with something that’s quite important for any serious wine region these days. The wine-tourism dollar is there for the taking for the canny businesses, and Rioja Alta has some great places to go for the adventurous wine lover.

Logroño, the ‘capital’ of Rioja, is an important historical town on the pilgrimage route to Santiago. It’s the place to base yourself for an extended tour of Rioja, home to bars, restaurants, famous wineries…and of course the offices of the Consejo Regulador.

Haro, to the west, is of huge historical and present importance. In 1880 it was the site for a train station that linked Logroño with the important port of Bilbao. With a ready market and method of shipping available, some of the most famous wineries in Rioja (including R. López de Heredía, CVNE, Duque de Montezuma, Gómez Cruzado, Bodegas Bilbaínas, La Rioja Alta, and the two late joiners Muga and RODA) set up wineries in what is now known as the Barrio de la Estación, where each year a festival weekend sees the wineries open their doors to the public for a weekend of drink, food, music and otherwise good fun.

It’s also the setting for the famous, annual Wine Battle on Saint Peter’s Day each year. And finally, for those of you who love a pub quiz fact, it was only the third town in Europe, behind London and Paris, to get electricity.

Outside that you’ve got the castles, monasteries, stunning medieval towns and villages such as Briones, and the brilliant museum at Bodegas Vivanco which is just a fabulous experience to let your inner wine geek run free.

* For more information about the regions, wines and winemakers mentioned in this article, as well as more information on visiting Rioja Alta, please contact the Rioja Wine UK team on Rioja@thisisphipps.com.

* The Rioja Somm’er School 2024 is now open for applications. Taking place between June 24-27, the Rioja Somm’er School will be a four-day trip to the region complete with winery visits, seminars and tastings. Eight sommeliers will have the opportunity to visit leading wineries across the region’s three zones, meet with pioneering producers and discover both traditional and newer styles of wine being produced in the region.

* UK-based sommeliers and on-trade buyers can apply for a spot on the Somm’er School here: https://survey-eu1.hsforms.com/1oMsBpLZHTeyFzOk1nNd5hAf9pul

* To learn more about Rioja and its wines, visit the Rioja Wine Academy, a fantastic online platform offering free educational courses for trade and consumers alike. There are six courses available on the platform from introductory courses right through to the Rioja Wine Diploma, which covers everything from grape varietals to styles of wine, regulations on viticulture to gastronomy and history. To register for a course, head to riojawineacademy.com.

* Mike Turner is a freelance writer, presenter, educator, judge and regular contributor for The Buyer.

* Funded by the European Union.