This Q&A debate was first published on its consumer site by Hofmeister, which claims its unique Helles lager taste is down to the 1516 Reinheitsgebot German Beer Purity Law that states it can only be brewed using three ingredients. Which in Hofmesiter’s case includes pure mineral water from an underground lake beneath the Bavarian Ebersberg Forest, locally grown barley malted in its own malthouse, and hops from the award-winning Hallertau region. Hence it’s case for claiming sense of place is just as important in beer as it claims be in wine…But what do Emma Inch and Richard Siddle think?

Emma Inch: So, Richard what do people in the wine trade mean when they talk about terroir?

Richard: Well, how long do we have? The issue of terroir and what it actually is has been the subject of so many books, essays and dissertations that you could probably fill a library with them.

Its a vineyard’s unique terroir, like here in Tejo in Portugal, that will determine so much of the style of wine

In a nutshell when a winemaker talks about terroir, they mean the land, the soils, the specific site from which the vines are planted and the grapes are grown. They can only make wine based on the ingredients, the conditions and the environment that nature has given them.

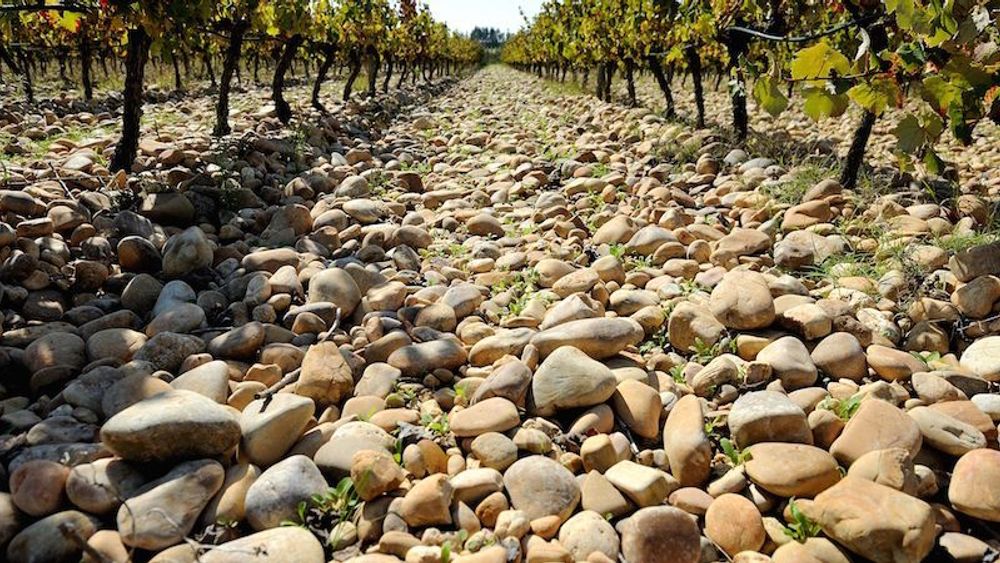

So terroir is not just one specific thing. It is a myriad of factors covering a whole spectrum of different influences. It principally means the soils, the actual land in which the vines are planted. Which in itself is a truly complex area covering geology going back millions of years that has resulted in the soils, the rocks, the stones in which the vines live.

Then there is the climate. How many days of sun does that vineyard get a year? What is the rainfall like? Do the vines need to be irrigated and drip fed with water? Are they affected by wind, by the atmosphere? You also have to take into account the aspect of a vineyard and how and where it is grown. Is it on a valley floor, or up and down a mountainside? If so how steep is the mountain range? How many feet above sea level is it?

What impact does that then all have on night and day temperatures in the area? Many wine regions will have big differences in diurnal temperatures which also have a big impact on the make up of the grapes, how much sugar they produce and water they need to use.

It’s why many of the wines you see in your local supermarket or on a wine list in a restaurant are described as being a ‘cool climate’ wine. As it describes the growing conditions, and average temperatures that the grapes are grown in. Day and night.

Proximity to the sea is also a key factor. You will often hear winemakers talk about a coastal or maritime influence on their wines. By which they are talking about the winds that blow in from the sea, bringing with it moisture, salt and big changes to the temperature.

Emma: So it’s not just about the specific piece of land that vines are grown on?

Richard: Far from it. There is also now so much more consideration given to the biodversity of the land and environment around vineyards and the impact they then have on the vines and the grapes. That means going right through to the insects and animals that live in and around the vineyard. It means drilling right down to the different types of plants, flowers, cover crops, trees, bushes, that grow naturally in the area. All of which goes towards creating its own mono culture that in itself is unique to the specific area.

Here’s Ben Walgate happy to get his hands dirty with biodynamic and natural wine practices at his English winery, Tillingham Wines

It is all those factors, and more, that come together to create and generate a specific terroir, a sense of place from where the grapes are grown and the wine is made from. It’s easy to see how this subject has captured the imagination of winemakers, producers, farmers, writers and wine buyers the world over.

Richard: That’s enough about wine. But do any of these elements and factors we talk about in terroir for wine also have an influence on the type of beer any particular brewer can make?

Emma: We can talk about terroir in beer in some of the same ways you mention, but it’s a little contested and somewhat complicated to say the least. For a start, in wine you generally talk about just one ingredient – grapes – having the most impact on the flavour of the finished product. In beer, however, there are four main ingredients (sometimes more), all of which can be dried, boiled, fermented or in some other way manipulated on their way to the glass.

Probably the most well-known ingredient of beer is the hop. Hops are the flowers of the hop plant and contribute several important elements to the finished brew including bitterness, aroma, flavour, mouthfeel and a crucial preservative quality.

Hops are cultivated in several countries across the world, most notably Germany, the United States, Czech Republic and the United Kingdom (mainly England). The precise location where they are grown, and the corresponding climate, geology and soil quality, affects the type of hop that can be successfully cultivated and also the yield, aromas, flavours and amount of bitterness they can impart to the beer.

In wine it is all about the grapes – in beer it is the quality and origin of the hops that are so important

For example, the mild maritime British climate means that hops grown here tend to have delicate, complex aromas – often flowery or earthy – and work well in the kinds of drinkable session beers British people have traditionally valued. In contrast, hops grown in the semi-arid desert of Yakima Valley in Washington State tend to possess more tropical, fruity and piney aromas coupled with the ability to deliver higher levels of bitterness.

Similar factors can also be said to have an impact on barley – the most common grain used in the production of beer. Barley provides colour, body, mouthfeel, flavour and, through fermentation, alcohol to a beer but, unlike grapes in winemaking, barley is not used straight from the field. Between harvest and brew day it goes through a complex process called malting which involves controlled germination and kilning. In this way, the maltster’s skill arguably has as much of an impact on the barley as the climate or soil.

Another ingredient that contributes hugely to the finished pint and yet is regularly overlooked in terms of its importance, is water. The average pint of beer is 90-95% water and the make-up of that water varies from place to place in terms of its alkalinity, mineral and salt content, all of which have a huge effect on the finished beer. Some water profiles are better suited to certain styles of beer than others. For example, soft water that’s low in mineral salts is ideal for pilsner-style lagers, whereas very hard water containing high levels of calcium bicarbonate is better suited to brewing stouts and porters.

The final ingredient of beer is yeast. Yeast is a single-celled microorganism which, as in wine production, consumes sugars and produces alcohol and carbon dioxide. In addition, however, yeast contributes much in terms of flavour and aroma to the finished beer including fruity esters and spicy phenolics. Although many modern brewers use dried, powdered yeast, purchased from major yeast producers, others use house strains, collected and re-pitched over many years and thus unique to that location. In this way, the brewhouse itself becomes a major factor in the terroir of beer.

Emma to Richard: What would be good examples of wine regions with specific terroir in wine and why?

Richard: That’s a great question and arguably the best answer is each and every wine region and vineyard in the world has its own unique terroir. But there are some areas where terroir and a sense of place is much more important than others. It also usually means the price of the wine that comes from those distinct, unique wine regions is a lot more expensive. They are the wine regions that also usually make the best wines that people want to drink and write about.

What side of the river you are on in Bordeaux dictates everything

Let’s look at France and two of its most famous and prestigious wine regions: Bordeaux; and Burgundy. Both are very distinct and famous in their own right.

In Bordeaux it is all about the river that runs right through the city and surrounding area, splitting its wine regions into its prestigious Right Bank and Left Bank zones either side of the river.

The Left Bank is where the region’s most prestigious producers, the First Growth names, are due to the quality of the soils and land with a gravely topsoil and limestone underneath. The soil composition can vary greatly from one plot to the next. It means it is suited to Cabernet Sauvignon, the primary grape variety in the area, followed by Merlot and Cabernet Franc. On the Right Bank the conditions are better suited to Merlot and Cabernet Franc thanks to the clay and limestone soils and less gravel.

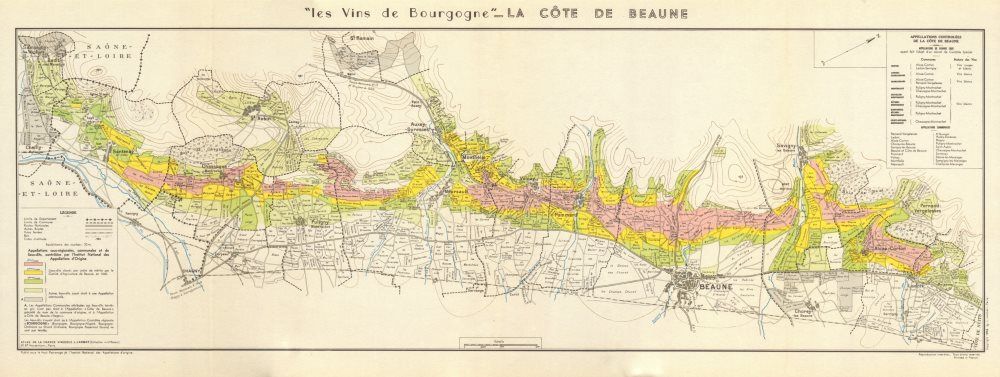

The devil is in the detail when working out who owns what part of Burgundy

Terroir arguably has the biggest role to play in Burgundy than in any other region or country in the world. Here everything depends on your specific terroir. So much so that you can have vines one side of a road that make the best of the best, most coveted, rewarded and expensive Grand Cru wines in the world. And on the other you can have vines that grow grapes that just go to the nearest co-operative to end up in a supermarket shelf for a couple of euros or as a house wine at the local brasserie.

In Burgundy it is all about the soils. That’s what makes the difference. What mix of limestone, clay, gravel, and sand you have can be the difference between making prestige or run of the mill wines.

Emma: Anywhere else outside of Europe?

Richard: Then you can travel to the Napa Valley in California, again one of the most prestigious and sought after wine regions in the world. Here it is all about the influence of the sea, and the winds and daily fogs that sweep in from the coast every night and morning, often leaving a blanket of fog over the region.

Slowly but surely during the day the sun burns through to give the vineyards afternoons of intense heat. But it is the duvet effect of the wind and fog that protects the grapes so much. In turn that comfort blanket controls the sugar and alcohol levels in the grape so that they go on to create wines with such elegance, depth, texture, structure and balance. Wines that also become some of the most expensive wines in the world just thanks to the land, the place where they come from and the weather conditions they live in.

The fog and wind plays such a part in the wines made in Napa

Richard to Emma: How about the beer world? What regions and countries are famous for a specific style of beer and why?

Emma: Beer is brewed and drunk in just about every corner of the world and, contrary to popular belief, it’s not a simple drink and doesn’t fall neatly into two categories of ‘yellow and fizzy’ or ‘brown and warm’. In fact, according to the Beer Judge Certification Programme, there are more than 120 distinct styles of beer and this is probably a conservative estimate.

Many of these styles grew up in specific geographical locations – including beer-drinking nations such as Belgium, Germany, the Czech Republic, and the United Kingdom – at specific points in time, as a result of available ingredients, dominant brewing techniques and the characteristics of the wider beer drinking culture.

For example, Belgium is probably the most famous brewing nation on earth and is responsible for introducing the world to a wide range of beer styles. Throughout the Middle Ages, Belgian abbeys became centres of brewing. Monks were allowed a certain amount of beer each day, in part because, at the time, it was safer to drink than most water.

One beer style derived from Belgium is lambic, which originates from a small area to the south west of Brussels. Lambic is made from barley, wheat, and aged hops. One thing that distinguishes it from most other beer styles is the fact that on brew day, rather than yeast being added in a carefully measured cultured form, the brew is instead transferred to an open fermenter – a coolship – and left overnight, open to the environment, where wild yeasts and bacteria – arguably unique to this precise location and point in time – cause a spontaneous fermentation and contribute to the distinctive flavour of this Belgian classic.

England, of course, is another great brewing nation. Historically, the English are famous for brewing pale ale, an amber beer that possesses a balance between sweetness and bitterness that lends itself to drinkability. A number of factors contributed to the dominance of this beer including the availability of ingredients, and the convivial environment of the English pub where beer is often drunk in ‘rounds’, and therefore prized for its ‘sessionability’.

The wish to export beer to other parts of the British Empire led to the development of India Pale Ale (IPA), a beer brewed with additional hops which, due to their antimicrobial properties, allowed the beer to better survive the long sea journey. But one of the main factors that contributed to England’s dominance as a brewer of pale ale was the water, notably the water in the small Midlands town of Burton on Trent. The high sulphate, calcium and magnesium content of the water there, coupled with low levels of sodium and bicarbonate, made Burton on Trent the perfect location for brewing great beer. At its height in mid-nineteenth century, it was home to more than thirty breweries and became a household name across the world.

However, Burton on Trent did not keep the secret of its water for long and nowadays any brewer, in any part of the world can brew a pale ale by ‘Burtonizing’ their water to give it the same profile as that found in the town. And, in many ways, this is the crux of the issue around any discussion of terroir in beer.

It’s no longer as straightforward as ‘beers brewed in Belgium taste like this’ or beers brewed in England taste like this’. This is a global world in which ingredients, rather than being used at source, are often shipped many thousands of miles before being brewed into a beer. A hop from sunny Yakima is just as likely to be found in the hop store of brewery in rainy Manchester, and breweries in both the United States and England are experimenting with Belgian-style coolships of their own.

Richard to Emma: So we’ve been asked specifically to look at Hofmeister and the fact it is brewed next to a forest in Bavaria. What makes that so important and Bavaria so different as a brewing area?

Hofmeister is no longer brewed in the Midlands but the new relaunched version comes from a traditional German brewer in the heartland of Bavaria

Emma: The renowned beer writer, Michael Jackson, wrote ‘If Germany is the world’s most famous brewing nation, then Bavaria is its cellar…’, such is the high esteem in which he held the beers from that region. As in Belgium, German brewing was initially based in abbeys where beer became known as ‘liquid bread’ due to its ability to provide nutrition during periods of fasting. Over time, Bavaria has become synonymous with a number of different beer styles including smoky rauchbiers, cloudy weissbiers, and refreshing helles lager.

The Hallertau region of Bavaria is the largest hop-growing area in the world and local beers showcase these beautifully. Hops have been grown there since the eighth century but cultivation grew immensely after the introduction of the Reinheitsgebot – or Bavarian Beer Purity Law of 1516 – which decreed that beer should only be brewed from malted barley, water and hops (at the time the existence and importance of yeast was not understood). Although this ruling has been amended and limited in power over the centuries, arguably it – together with ideal hop-growing climate – has had a lasting impact on the perception of Bavarian beers across the world as pure and full of quality.

Emma to Richard: Is Germany and Bavaria also well known for creating unique wine styles?

Richard: Absolutely. Less so, though, in Bavaria. The winemakers have left that particular area of Germany mainly to the brewers, probably because there are so many other areas to make wonderful, unique, distinctive, world leading wines. That said Bavaria makes up around 6% of Germany’s total vineyards, with 6,310 hectares, of which 81% go towards making white wine, primarily from the Müller-Thurgau variety.

Again we have the importance of rivers to thank for all the wonderful wines from Germany. The Rhine and Mosel rives to be exact. As they weave their way across the country they pass through different regions. The Mosel region itself is one of Germany’s most famous and prestigious. The south of Germany, however, is best suited to winemaking, like in the Baden, as it so much warmer and vines can enjoy many more hours of sun during the year.

Richard to Emma: So what about Hofmeister specifically. What makes it so unique?

Emma: As I said earlier, in our global world, a lot of beer is somewhat divorced from a sense of place. Brewing ingredients and knowledge that used to be very localised, are now internationally available, meaning that accomplished IPAs are brewed in the United States, and lambic-style beers are fermented in the heart of the British countryside. Terroir is therefore hard to claim when it comes to beer, but there are some breweries using local ingredients and traditional techniques which can be said to endow their beers with at least some sense of place. And Hofmeister is brewed at one of them.

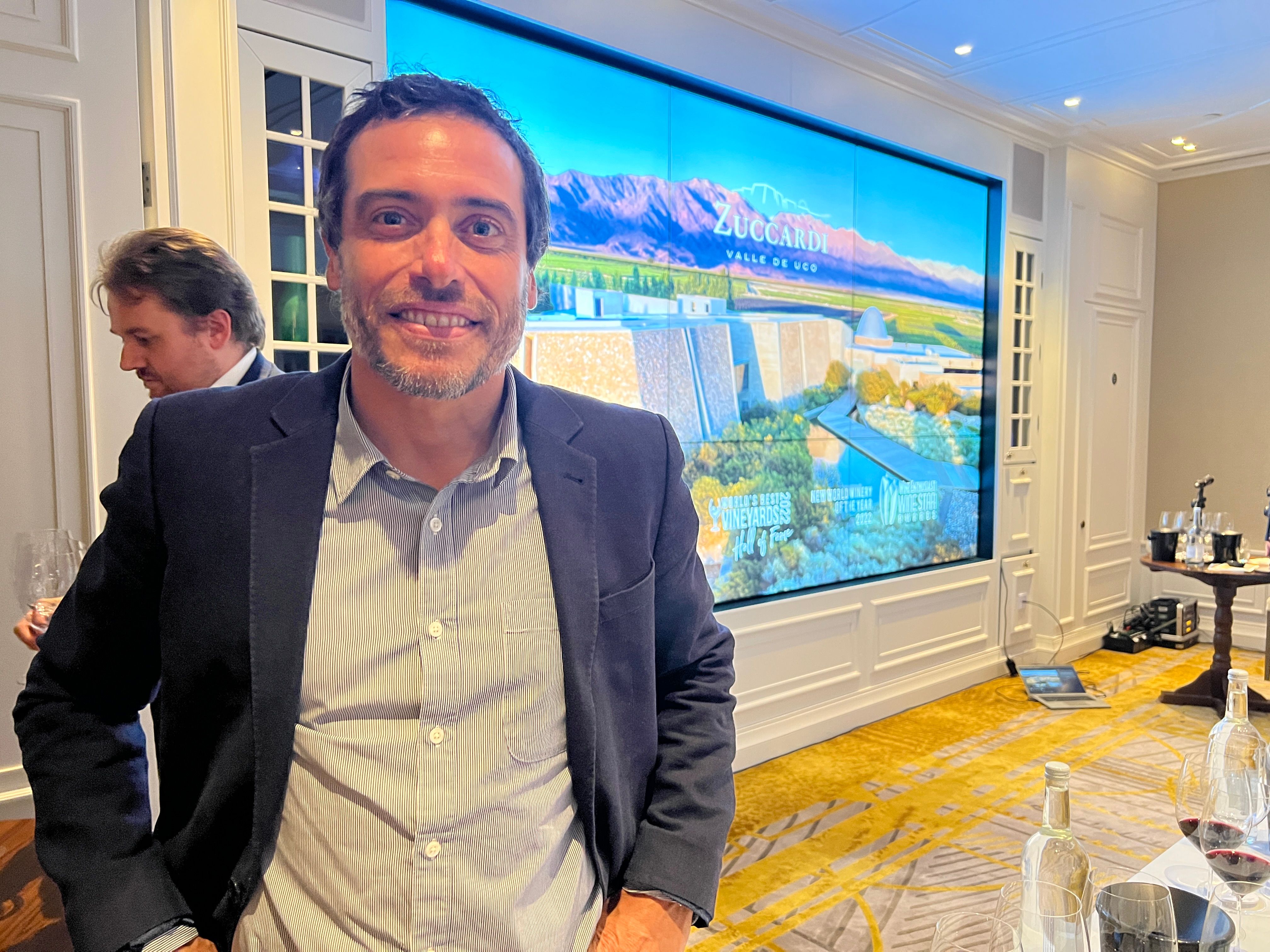

Richard Longhurst and Spencer Chambers – Hofmeister’s founders – spent a long time looking for a brewery they trusted to brew the re-launched Hofmeister. After visiting a number of breweries, they eventually settled on Privatbrauerei Schweiger, a family brewery in the heart of Bavaria. Schweiger uses water from its own well in the Ebersberger Forest, Bavarian hops, and its own yeast strain. The barley is also grown locally, and Schweiger is one of the last breweries to have its own maltings on site meaning it has full control over the processing of the grain. The brewery brews in accordance with the Reinheitsgebot and carries the ‘Slow Brewing’ seal, a sign of quality and integrity.

Richard Longhurst and Spencer Chambers saw the opportunity to relaunch the Hofmeister brand as a quality, authentic Bavarian Helles lager

Emma to Richard: Anything else you would like to say?

Richard: Only to say that when it comes to understanding wine, knowing where it comes from is paramount in being able to predict what it will taste like. And whether you will like it or not.

Terroir and sense of place means everything in wine. It might not mean so much to the mass produced, almost factory produced wines that we see around £5 in our nearest supermarket. But get up to £7 to £8 and certainly over £10, then you really are getting into the terroir territory.

So please next time you are buying a bottle of wine, take a moment to read the back label, and see where it was made and think about the kind of country, environment, climate and land where it was made. It will not only help you understand a little more about what it might taste like, but it will whisk you away to that country or wine region when you are drinking it.

Richard to Emma: And any final thoughts from you?

Emma: Discussions about terroir in beer are never straightforward. It’s hard to say that any beer is completely of one place, but location, climate and geology undoubtedly have an effect on each of its key ingredients. Whether I can say I have part of a railway arch in Bermondsey, the sunshine of Yakima, or a piece of the Bavarian forest in my glass, it’s hard to say. But, as with wine, knowing where your beer and its constituent parts come from, and learning some of the stories that surround it, can only enhance your enjoyment of the drink.