Tell us about your new book and what you have looked to achieve?

There are two significant changes with this new book. First, I’ve written it in partnership with New York-based entrepreneur Michael Aaron Flicker, who brings a wealth of real-world business insights. He’s scaled nine companies and has seen first-hand what works.

Second, the previous two books - The Choice Factory and The Illusion of Choice - described important behavioural biases, the evidence underpinning them, and how brands can apply the insights quickly and easily to achieve reliable results.

People have consistently told me they value real world examples, so this time, I’ve flipped the approach. We look at leading brands, and examine the marketing moves they have made that align with what we know about human nature.

Hacking the Human Mind explores how major brands use behavioural science to build success upon success

It’s a better approach than simply copying what other brands do, because it’s almost impossible to isolate which particular tactics out of hundreds have triggered success. Overlaying a lens of behavioural science gives you a way to zone in on the active ingredient in the marketing mix.

How have you picked the brands that you analysed - what criteria did you use?

We selected brands that are big enough to be household names - some of the world leaders. We wanted to pick brands that are impressive either because they’ve grown to dominate their category - like Amazon, Facebook or KFC, plus some that have grown remarkably quickly, like Klarna and Liquid Death.

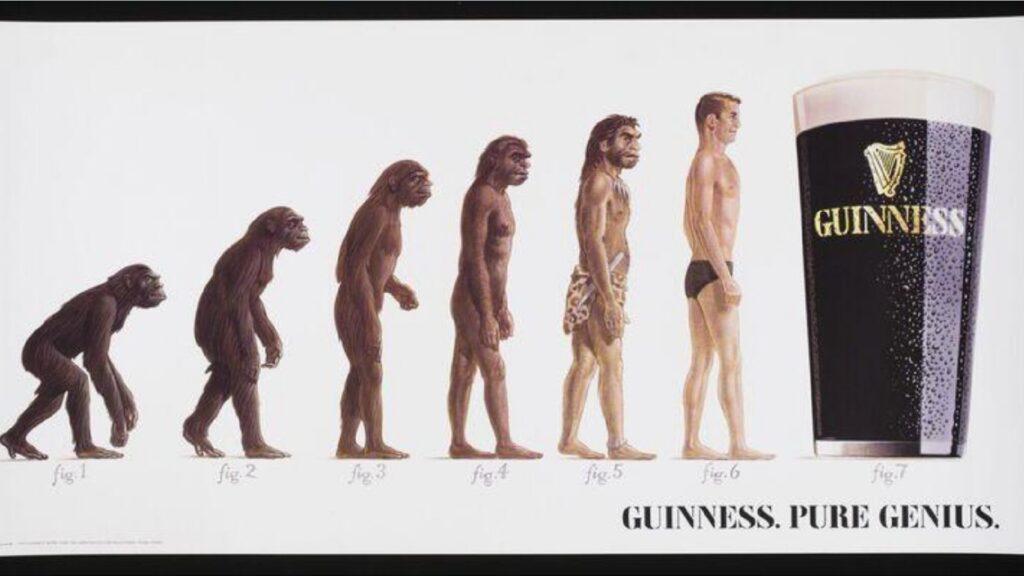

We also chose a few that have stood the test of time, and so must be doing something right - like Snickers and Guinness. It’s not surprising to me that these brands have aligned with some key behavioural biases, they simply would not have succeeded otherwise.

We also included a mix of categories, including quite a few drinks brands - Aperol, Guinness, Pumpkin Spice Latte, Milk Marketing, Red Bull and Liquid Death.

Are there any common themes and uses of behavioural science that run through all the brands that you have picked out or are they very individual in their approach?

There are some biases that are just so impactful that almost every brand can and does use them - things like social proof. But we wanted to cover a range of biases so we have tried to avoid too much overlap.

And there are other themes that I think should matter to every brand. One of these is the risk of claimed data.

Hacking the Human Mind authors: MichaelAaron Flicker and Richard Shotton

Every brand does market research, and traditional market research can be misleading. It relies on what people say drives their behaviour, but evidence shows that there is often a significant disparity between what people say drives behaviour, and what actually does.

One study showing this was carried out by Adrian North at Leicester University in 1999. His fascinating experiment looked at the impact of music on people’s wine-buying choices.

He found that when a supermarket played French accordion music, French brands accounted for 83% of wine sales. When the music was German, 65% of wine sales were German. So it’s clear that the background tunes played a significant role. However, when questioned, only 2% of people mentioned music as a factor influencing their decision-making. Even when directly asked, most (86%) denied that music could have swayed them.

These customers were not deliberately lying. It’s simply that we as consumers are unaware of all the elements that motivate our decisions. In the words of social psychologist Timothy Wilson, we are strangers to ourselves.

This is important for any brand to keep in mind when conducting market research. It’s far better to observe behaviour in the wild and observe how people genuinely respond to differing stimuli, like the music in North’s study.

Any particular elements of behavioural science you can pick out from your book and your research that applies to drinks brands and what is effective in that category?

There don’t seem to be category-specific insights, but there may be biases that are more likely to be pertinent in some sectors. For example, loss aversion in financial settings, or pricing tactics for consumer goods.

There’s one insight I would like to pull out, though, that I think could be particularly useful for drinks brands. I’ve mentioned social proof already, as it’s pretty ubiquitous. But when you are selling products in social settings, such as drinks in a bar, there is scope to use social proof quite laterally.

The Aperol effect: Seeing people drinking a different type of drink makes other customers want to buy it to find out what they are missing - it was the same effect with Magners and ice

Aperol is a great example of this.

Their bright orange drink and branded glassware effectively apply lateral social proof. Because the colour is so distinctive, just one or two people drinking it in a pub makes it look like a common choice. That’s quite different from say a Gordon’s and tonic, which, if ordered in a pub, is essentially invisible.

The study showing the power of lateral social proof was conducted in 2008 by Kees Keizer at the University of Groningen. They identified an alleyway where lots of bikes were parked, and they attached flyers to the handlebars. They then recorded what the owners did with these flyers.

On some occasions, the researchers had tidied up the alleyway, leaving it pristine. On others, they had dropped pieces of litter on the ground and graffitied the walls.

In the litter-free set-up, when the implied social norm was that most people took their rubbish home, only 33% of cyclists threw their flyers on the ground. However, in the messy set-up, the perceived social norm was that many people littered, and then 69% of cyclists added their flyers to the litter.

This shows that people are led by what they think other people are doing. This is relevant to drinks brands, because if it looks like many people are choosing your brand, then customers will copy this behaviour. So, how can you make your drink brand more visible?

Are there examples of when using behavioural science has not worked for a brand - or they have chosen the wrong “behavioural” triggers in their branding?

Yes, on the flipside of social proof is the idea of negative social proof. Since people copy what they think other people are doing, if you make an undesirable behaviour appear common, you could inadvertently be encouraging it.

Evidence that this happens comes from a study by psychologist Robert Cialdini at Arizona State University. He ran an experiment at Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, where visitors were stealing a ton of beautiful petrified wood each month.

For the study, the researcher planted pieces of the wood at three spots close to pathways and monitored thefts via CCTV. On two of the three routes, they displayed signs, while the third was left sign-less as a control.

With no sign, 2.9% of the wood was stolen. The first sign, which stressed the damage done to the park by stealing - “Please don’t remove the petrified wood from the Park, in order to preserve the natural state of the Petrified Forest” - reduced the theft rate to 1.7%.

However, when they purposefully misused social proof - “Many past visitors have removed petrified wood from the Park, changing the natural state of the Petrified Forest” -the theft figure jumped to 7.9%.

As Cialdini suspected, telling people that theft was commonplace reduced the perceived transgression of the crime, so it became more popular.

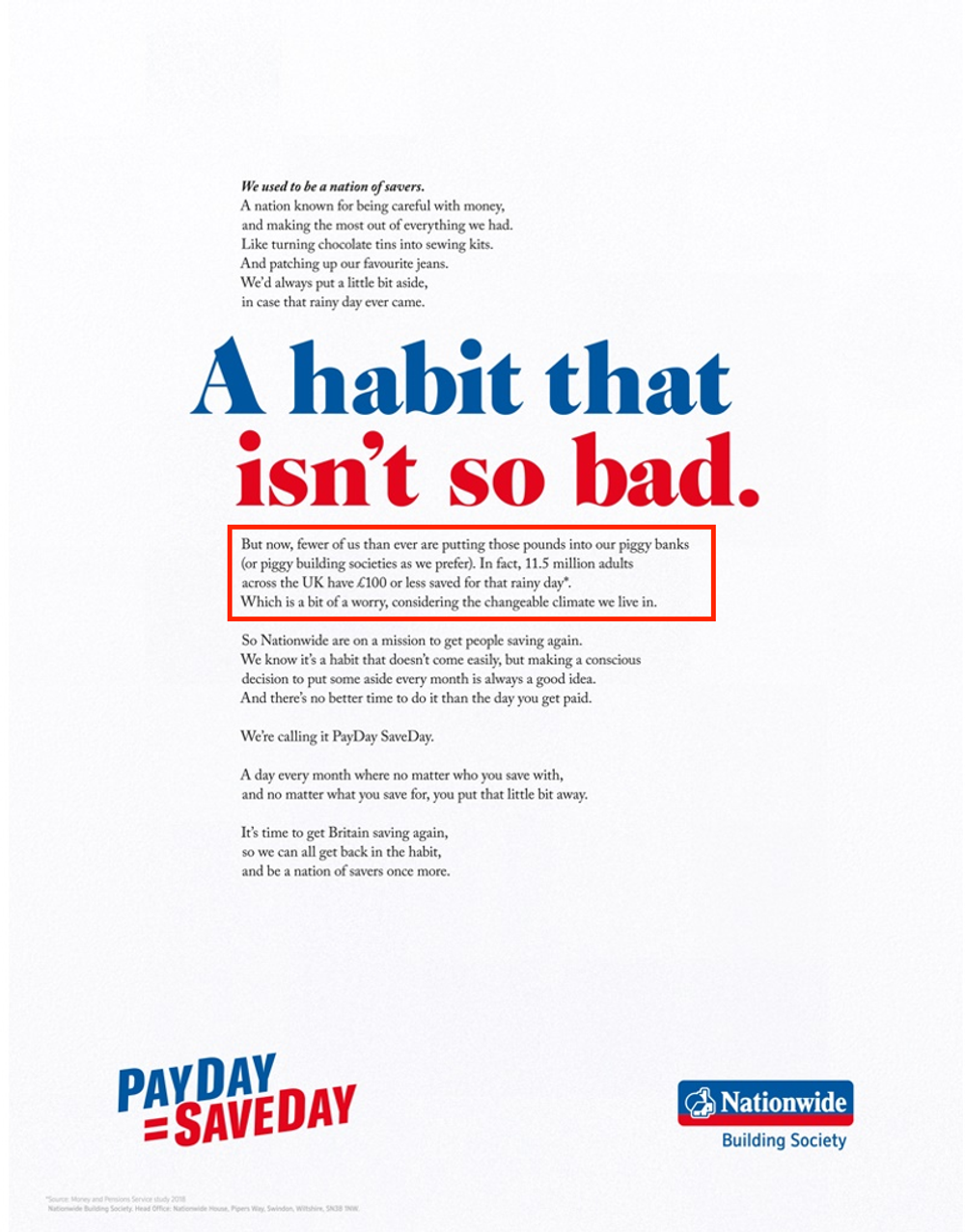

We’ve seen this mistake made relatively frequently. Here’s an example from Nationwide Bank, which flags the frequency of poor savings behaviour, making it seem more acceptable.

Brands and businesses can get it wrong too...like here with Nationwide Bank's advertising message that normalises bad spending behaviour

Brands should take care not to emphasise the frequency of an unwanted behaviour as this normalises it. Instead, highlight how common the desired behaviour is. And if that’s not possible, emphasise that it’s a growing behaviour.

How do you guard against that?

I’ve said it before – but it’s really important to conduct tests. The findings from behavioural science are not hard-and-fast rules, and there are occasions where some will work better than others. The only way to be sure is to run studies like the ones we talk about, where you can observe behaviour in the real world.

Create set-ups where the only factor that differs between two or more conditions is the one you are interested in, say, different forms of wording the same offer.

For those who are not familiar with behavioural science for branding, what would you recommend they do to better understand how useful it can be?

The first step to take is to read Hacking the Human Mind for lots of tips! It’s an easy read. In writing it, we have taken to heart a study showing that simple, clear writing is more authoritative than complexity.

It may sound counterintuitive, but there's good evidence to back up the assertion. It’s a study written up in the brilliantly named paper: “Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with using long words needlessly”, which was published in 2006, by Princeton psychologist Daniel Oppenheimer.

He gave participants one of two versions of a dissertation abstract to read. One version was left unedited, and was riddled with technical jargon and complex wording. The other was simplified.

When asked to rate the intelligence of the author, they found the author 13% smarter when the text was simplified (4.26 vs 4.8 on a 7-point scale).

This is one of the reasons why I always try to keep my writing simple. I want readers to be able to process the content quickly and easily. Simple writing also suggests simplicity of concept - making it more likely you’ll give them a go. So you won’t struggle with any of my books, plus you can dip in as the chapters are short.

Each chapter ends with our key takeaways from the case studies we discuss, so you can start applying the biases in your business straight away.

Do you think brands and businesses are more open to using and working with behavioural science?

Yes they are, and I think this is because people are drawn to the evidence-based nature of it. Marketing often relies on intuition and experience - which are still important, of course - but behavioural science draws on a catalogue of rigorous studies.

The major brands and businesses that are covered in the book Hacking the Human Mind

In marketing, it’s easy to become obsessed with the next big thing, be that Big Data, AI, and other new technologies. Behavioural science, rather comfortingly, deals with what ‘doesn’t change’ in human nature, which is appealing in a fast-paced business environment.

The shortcuts in decision-making that we all take are hard-wired and often have their foundations in evolution. They run deep, and define our interactions with new innovations, rather than the other way around.

That’s not to say that behavioural science is all you need at every stage. It isn’t the whole answer, but rather, a tool that can support your thinking whatever your challenge.

AI is all the rage, but does behavioural science suggest any drawbacks we should be aware of?

Well, yes, as I mentioned, behavioural science describes our instinctive behaviour which in part defines how we respond to technologies, including AI. One of the most relevant observations here is that we equate time and effort with quality. It’s called the illusion of effort. The problem with AI solutions is people know they can be almost zero-effort and instantaneous.

This isn’t just speculation. A recent study led by Kobe Millet at Vrije Universiteit looked into the effect of labelling an item as AI-generated on artistic appreciation, perceived creativity and purchase intention.

The researchers recruited 800 participants online and showed them two nearly identical drawings of a human skull, both created by human artists. They randomly labelled one of the images as AI-generated and the other as human-crafted.

Participants were asked to rate their artistic appreciation of each drawing, as well as perceived creativity and purchase intention on scales from one to seven.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the drawing labelled as human-created was rated a 4.59 for artistic appreciation, whereas the one labelled AI-generated scored 3.39 - a 26% decline. The same was true for perceived creativity – ‘human-created’ versions received a rating of 5.30, while the ‘AI-generated’ had a score of 2.75 – a 48% reduction.

Most significantly for businesses though, were the results for purchase intention. Drawings marked as human-created received a score of 4.85, but those marked as AI-generated obtained a score of 3.02 - that’s a 38% decrease. This could translate into a major dent in business for companies that embrace AI too enthusiastically.

If you’re using AI there are a couple of sensible options: first, you can of course keep it quiet. But, if AI involvement is obvious, it will help demonstrate value if you can highlight the time, effort and expertise that’s gone into creating the perfect AI output.

Third – and we are starting to see evidence of this already – you might choose not to use AI, and instead emphasise the fact it was hand made. Because in the current climate, this helps to preserve perceptions of value and stand out in a field of AI-fatigue.

- You can find out more and how to buy Hacking the Human Mind here. You can also sign up to a masterclass course given by Shotton and Flicker on how to use behavioural science techniques in your business by clicking here.

- You can sign up to their behavioural science podcast here.

- Richard Shotton has also written two other bestselling books on behavioural science The Choice Factory and The Illusion of Choice.