“The vines don’t care whether there is a war or not, they still need tending, harvesting and processing on schedule. So our workers had to work with aircraft flying over their heads, bombs being dropped close by. And believe me – we did not push them,” says Vitali Shmulevych.

Ukraine wine stand, London Wine Fair, May 15, 2023

One of the highlights of this year’s London Wine Fair was the Ukraine wine stand, situated slap in the middle of Olympia, manned by producers and mobbed by visitors curious to know what a wine from this war-torn country tastes like.

On October 9, the UK trade will get another opportunity to find out with Wines of Ukraine’s inaugural tasting in London, at 67 Pall Mall. Twelve of the fifteen wineries that make up this craft wine association will present 60 wines from six regions, including Chateau Chizay and Stakhovsky Wines from Zakarpattya, Shabo (Sparkling) and Bolgrad from Odesa, Graevo from Zaporizhzhia and Beykush from Mykolaiv.

A renaissance against all the odds

An exciting time for Ukraine wine: Tanya Olevska © Serge Serdiukov

“Despite the awful things going on in our country, this is a truly exciting time for Ukrainian wine following a lot of investment over the past few years, and growing interest in western markets,” says Tanya Olevska, who moved from Ukraine to Cambridge last year to become Wines of Ukraine’s UK representative.

Olevska dates the current renaissance to the early 2000s when, alongside cultural and political liberalisation, there was growing interest in modernising the wine industry. Like those in other former-Soviet nations like Georgia, Armenia and Moldova, it had focused on quantity, with inexpensive sweetish wines usually the result. Growing contact with western winemakers, increased familiarity with modern techniques and styles — and the desire to reach lucrative western consumer markets — helped drive a change towards quality, which continues despite Russia’s war.

Today there are some 110 wineries across 36,600 hectares, an area equivalent to plantings in Piedmont; there are five very big estates, and some tiny producers making fewer than 10,000 bottles each year, but the majority produce between 20,000 and 60,000 bottles. Odesa has become the largest and most important wine region following Russia’s 2014 invasion of Crimea which, until then, had been Ukraine’s biggest region and the source of grapes for many other regions too.

“Crimea really was – and is – our treasure. The ancient Greeks planted vines here and it was the heart of our wine industry,” she says.

But perversely this loss doesn’t seem to have halted the renaissance – production has moved to other regions, notably Lviv and near Kyiv which didn’t historically make much wine. Other factors have been key in the resurgence: domestic consumption has grown (fuelled by national pride); there has been an easing of legislative restrictions which had impacted small producers; the price of imported wine has risen sharply following the collapse in the value of the Hryvnia; and then there’s the simple fact that Ukrainian wine is getting better all the time.

“Winemakers today work with stainless steel, amphoras, and oak barrels from France, Slovenia and Ukraine. Most wines are made by classic technology with artificial yeasts, and there is a trend to follow the low intervention philosophy, to reduce the use of chemicals in growing and processing,” says Olevska.

Fermentation in oak at Beykush winery

Vitali Shmulevych, CEO of both manufacturing and distribution company Alcoline and Bolgrad, the country’s biggest winery, echoes this.

“Despite the invasion, the industry continues to develop, unfortunately not at the same speed as before. But the world already knows about us, and it has helped more producers export their wines. For sure we had to modify our production process – we had to stop bottling when missile alarms started and continue when they had finished. This is our usual life now. Half of the country is fighting – the second half is supporting,” he says.

Most producers work with international varieties with Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir and Pinot Grigio particularly widely planted as well as Georgian varieties Rkatsiteli and Saparavi. Producers are increasingly working with native varieties including three whites – Sukholimansky ( a relative of Muscat) Telti-Kuruk and Citronniy Magaracha – and Odessa Black (a 1950s crossing of Cabernet Sauvignon and Alicante Bouschet, aka Alibernet) which famously produces dark, tannic, full bodied reds. And, although producers are still experimenting with what best works well where, regional differences are becoming clearer as producers focus more on terroir and less purely on quantity.

“In Transcarpathia, for example, the wines are more elegant and have the influence of the winemaking of Hungary and Central Europe, whilst in the Odesa region the land and the sunshine produce expressive, bright wines including from Odesa Black,” says Shmulevych.

Kolonist is one of the producers showing wines at Monday’s tasting

So what to look out for?

For those who like quirky wine, Biologist looks like a perfect bet. A new winery established near Kyiv, it produces three biodynamic wines from a range of different varieties that are blended and presented as pet-nats and still wines. It’s early days for this producer, headed by biodynamic wine convert Ihor Petrenko, but the non-intervention wines look perfect for somms wanting to show something truly left field. The Buyer caught up with Petrenko recently and talked to him about the conversion to biodynamics which you can read here.

For those wanting French influence and a more conventional upmarket style then Kolonist has a great range; the winery was established in 2005 in Danubian Bessarabia, near the border with Moldova and Romania and benefiting from the input of flying French winemaker Olivier Dauga. Tasted through by The Buyer five years ago, highlights include a full-on Odessa Black and a moreish Sukholimansky as well as some well made Bordeaux varietals.

Meanwhile, Bolgrad – based in the eponymous town of outside Odesa where Bulgarians set up a colony in 1821 – makes a wide range of wines many of which are now available in the UK for the first time. In July, Bolgrad’s owner Alcoline signed an agreement with Kingsland Drinks to import seven of its Select range, with bottles boasting the yellow and blue Ukrainian flag on attractive eye-catching labels. Retailing at £10 a bottle these have a good price/quality ratio, with Duo (a very moreish Chardonnay/ Sukhlimansky blend), a fresh Chardonnay (with 15% Aligote) and a medium-bodied, fruity Saparavi amongst the best of these crowd pleasers.

Separately, wine importers Swig has brought in two reserve wines from Bolgrad, a pleasantly-oaked, fruit forward Chardonnay 2022 and a well-made, quite full bodied, dark cassis fruit-charged Cabernet Sauvignon 2022, both retailing at around £18.50 apiece. Both importers have high hopes for the wines.

“When I first tasted the Bolgrad Select range, I could clearly see why they are the number one still wine brand in Ukraine,” says Kingsland wine buyer Kathryn Glass. “Despite a significant wine-making history there is no major Ukrainian wine brand in the UK and we hope a Kingsland Bolgrad partnership can address that.”

“Consumers might buy their first bottle of Ukrainian wine primarily out of interest, but with Bolgrad Select I am so confident in the quality I know they’ll repeat purchase,” she adds.

Challenges obviously still remain

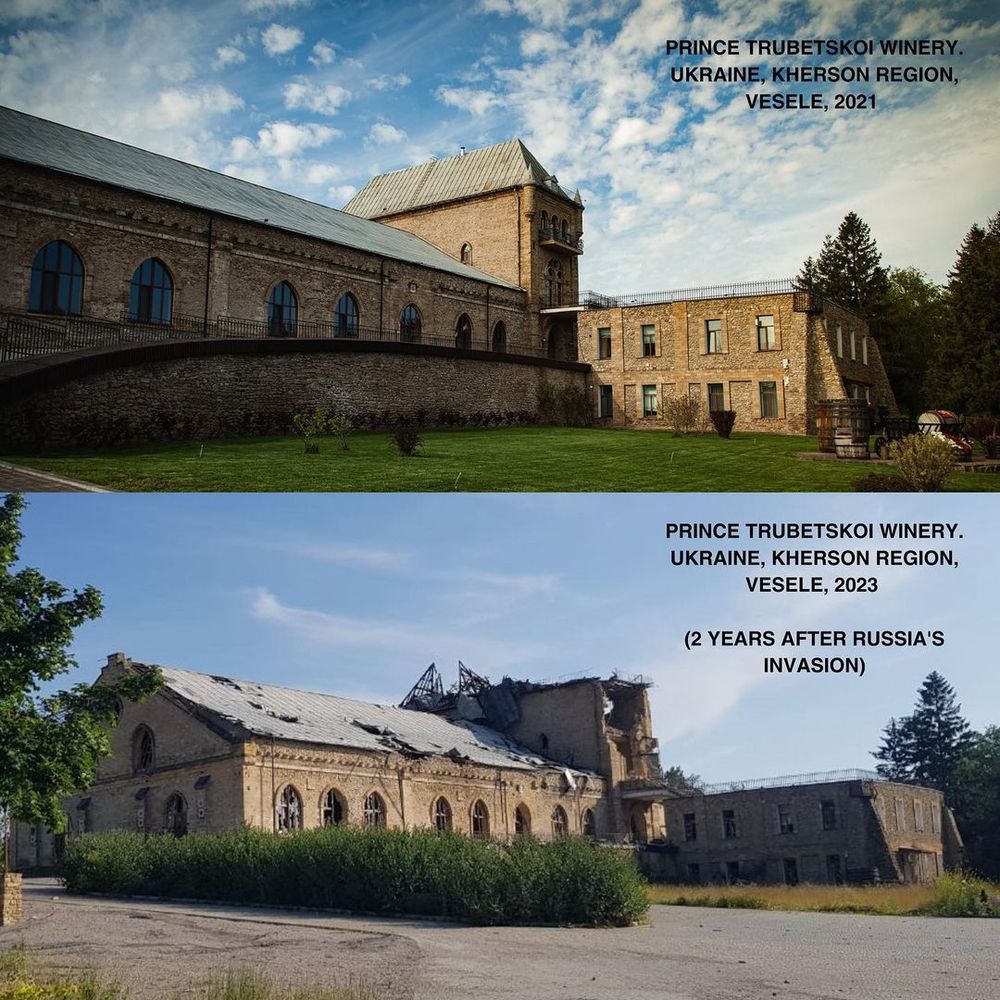

It will be impossible during and after this tasting not to bear in mind the terrible suffering that the Ukrainian people continue to endure. Russia’s invasion has changed this country forever, with many lives shattered. Although other more important sectors of the economy (notably energy and services, including transportation and tourism) have been more severely impacted, the wine industry has not escaped Russian brutality. Several wineries have been bombed and or ransacked, including the country’s oldest, Prince Trubetskoi, dating back to 1895 (and since reopened under the appropriate name, Stoic), Chateau Kurin near Kherson, which was recently retaken from the Russians by Ukrainian forces, and Cassia, a winery close to Kyiv.

A graphic reminder of the effects of war: Prince Trubetskoi winery now renamed Stoic

“The biggest challenge was broken logistic chains and systematic missile alarms – more than 10 hours per day in the beginning. You have to understand that the vines don’t care whether there is a war or not, they still need tending, harvesting and processing on schedule. So our workers had to work with aircraft flying over their heads, bombs being dropped close by. And believe me – we did not push them,” says Shmulevych.

The industry continues to be impacted by power cuts and high energy prices caused by the war, and by labour shortages with young men, in particular, more likely to be at the front than helping with harvest. High glass and other prices continue to be an issue even after the country’s main glass bottle factory Vetropack – almost destroyed in February 2022 – resumed operations earlier this year, with international funding.

“For all these reasons and others, our wines are not cheap – typically £12-25 a bottle whilst Cru wines can be as much as £40, but you are getting hand-harvested wines often from atypical varieties and made under incredibly difficult conditions,” says Olevska.

On the plus side, however, this year hopefully looks set to match the good 2022 harvest whilst confidence is returning to the sector, particularly amidst the growing international interest in Ukraine wine. Producers here have won a wide range of gold and silver medals including some from Decanter and IWSC whilst the industry is planning an export push into the UK and US to match the ones it has already successfully made into Europe and Japan.

“Now we have a window of opportunity – the markets have shown huge interest in us and we need to show ourselves in all our glory,” says Shmulevych.

Wines of Ukraine’s inaugural UK wine tasting will be held at 67 Pall Mall, London, on Monday, October 9 between 10.30 – 15.30. Registration is open to the trade and press and can be completed here.