They come in all shapes, and flavours, and are vital to the taste and the appeal of any beer on a back bar. But do you know much about the average, typical hop? Here’s Rupert Ponsonby to guide you…

Hops, ‘humulus lupulus’, the wolf of the willow, spread-eagles its string-like legs over hedges and trees. This member of the cannabis family has been so misunderstood for centuries, and so under appreciated. But, with the rise in the number of breweries in Britain from 300 to 2,000 in the last 10 years, their time has finally come. Here’s all you need to know about the world of hops.

HOPS’ PURPOSE:

The purpose of a hop, historically, was as a preservative, keeping beer in good condition, extending its life and giving it a refreshingly bitter edge. Hops have been used here in the UK since the 1400s, and were fingered for inciting Kent man, John Mortimer, to rebel against the King (it was the alcohol, of course). Beer at the time was a strong sweet drink using malted barley flavoured with spices, herbs, fruit, honey and the bark of trees. But it wasn’t until the 1500s that hops were widely used, brought to Kent by the Flemish weavers who arrived in search of wool.

By 1552, King Henry VI (see left) had passed laws to allow their use in beer, and short-life hopless beers were consigned to history.

Hops preserve beer, and there are examples of beers from 1869 still in good condition. But every month, a hop will lose its strength and definition, in the same way that a racy Sauvignon Blanc can transform to milder fruit.

WHAT IS A HOP?

It’s a tall climbing plant which can grow 20′ above the soil and 10’ below it. They can live for 20 years. The male and females flower on separate plants, and only the females grow the hop cones required for brewing. The cones’ lupulin glands produce grains of sticky yellow pollen, which include the volatile oils important to beer’s flavour – and the resins which give bitterness and preservative qualities to beer.

HOPS’ FLAVOURS

Hops (almost) make grapes look limited. New breeding programmes have let them fly. They can now do: orange (Goldings), lemon (Citra), rich orange (Target), apricot (First Gold), lime (Challenger); passionfruit (Galaxy). Past hop breeders were instructed to diminish what would now be seen as interesting, fresh, vibrant, in-yer-face flavours. And previously slightly dull and dusty hop regions like Australia (XXX) and New Zealand (Nelson Sauvin). But in addition, hops can do peppery (Saaz) and herbal (Hallertau Mittelfruh) as well. What grape does that, tell me?

HOP POWER

Twenty years ago, brewers split hops into ‘aroma’ (2-6% alpha acid), ‘dual purpose’ (6-9% alpha) and ‘hi alpha’ (9-20% alpha). But now we go much further with our knowledge. Hops burst with essential oils. Each oil brings a different flavour and, importantly, each reacts to the heat of the brewing process in different ways. Some, we are learning, hate heat and dissolve into vapour. So when you add a hop in the boiling process is almost as important to flavour as is which hop you actually use. Some hops are best added as the beer cools.

HOPS’ LOVE BREWERS

So that’s what a fuggle hop looks like?

Though hops have been imported and exported for centuries, their use in the 20th century was very conservative. Nearly every brewer used Fuggles (born 1875; 4% alpha acid; earthy/sensuous as per Syrah) and Goldings (born 1700s; 5% alpha acid; 30% myrcene; floral like Chablis) – a highly drinkable moreish combo.

And if you wanted fruity flavours in your drink, you ordered ‘lager and lime’ or ’a lemonade top’. Hops with exaggerated character were discouraged. But the massive growth in the number of UK breweries makes breweries keen to differentiate themselves from their competitors. Hops can do that quickly and with style. And hop growers are learning the value of a sexier name – the likes of Fuggles, Northdown and Hersbrucker replaced by Galaxy, Citra and Cascade.

HOP STORAGE

Hops were traditionally stored in great tall ‘pockets’, 5’x3’, and the outside inch used to get oxidised and smell like a rugger players’ cheesiest socks. Now light, heat and air are, wherever possible, kept away.

HOPS and PELLETS and OILS

Whole hops can be quite a handful

Whole hops are for most beer purists the holy grail. The 1” hop cones stripped from the hop bine in September by excitingly Dickensian machinery, and then dried from 80% down to 11% moisture to keep them in good condition. They are then scuppetted through a hole in the floor into a 5’ high ‘hop pocket’ sack; of 50 kilos weight. Each is stamped with the name of its farmer.

Brewers then cut out what they need; and cast it into the ‘copper’, containing the malted barley liquid which tastes surprisingly like Horlicks. The negatives of whole hops is that they can easily oxidise; they are messy to weigh and use, and give a mere 25% utilisation, the rest is lost.

Are you a pellet or a whole hop type of person?

Hop pellets by contrast have a utilisation of 35%; they are first ground and powdered, and then extruded through a hole like toothpaste, and look surprisingly like young ducks’ poos. They can be kept sous vide in aluminium foil in temperature controlled fridges to help them last. And are clean to use and easy to weigh. Purists may say some flavour is lost in the processing; but oxidation – there is none.

Hop oils have even higher utilisation at 65%+, and are easy to use. Purists would say that you can tell their harsh edge in a beer, and lack of suppleness. But I have made goats’ cheese with them, and the results were a wonder, each hop showing though with brilliant clarity. A gastronomic marvel, was my Hopping Goat.

HOPS in BRITAIN

In 1870, there were 70,000 acres of hops grown in Britain, spread through 53 counties and as far north as Aberdeen. There are 2,500 acres now, with Herefordshire and Worcestershire edging out Kent as the biggest region. And traditional 20’ high hops are now supplemented by dwarf hops, developed in Britain to be easier to establish and harvest, and with lower chemical needs.

Wilt, mildew and air borne pests are a constant scourge. Hops are very sensitive to terroir, and East Kent Goldings have gone so far to be given a PDO (Protected Designation of Origin). The salty air and light soils of Faversham Kent give them their own delicacy of flavour, much lighter than Goldings from the heavier clay’ish soils of Hereford and Worcester. British hops are on the rise.

HOPS in my BEER

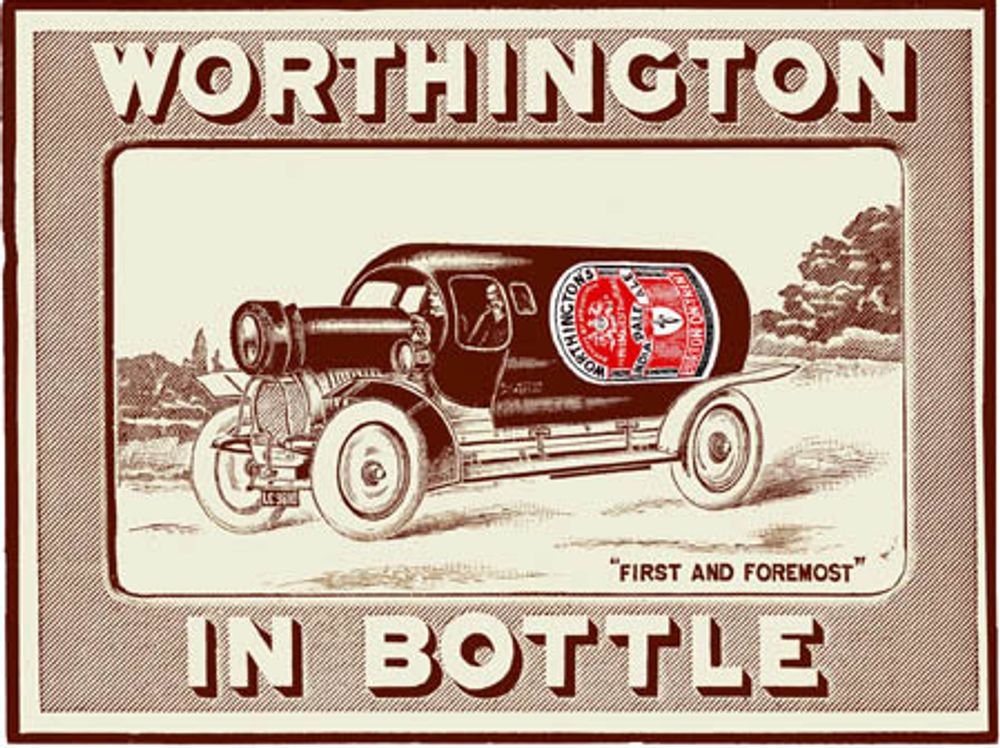

Worthington was one of the long standing IPA brands

India Pale Ale, developed in the 1820s, was highly hopped to keep it in condition in its three to six month journey to India. By the 1990’s it had all but died away, with only Worthington White Shield and a handful of others keeping the style alive. Now, the world is alive with them, and the US is pushing the boundaries furthest with double and triple infused IPAs. Some pucker the mouth, like licking gymnasts’ resin; but many are fine adversaries for a fiery curry, or a ripe stilton or mature cheddar cheese. The danger for microbreweries is not to lose ‘drinkability’. But the flavours ‘humulus lupulus’ can evoke and put grapes firmly in the shade.

OTHER USES FOR HOPS

Chocolate Bath Oliver biscuits have always used those earthy Fuggles; and hop pillows are meant to induce sleep; and hop petal confetti beats that revolting paper confetti every time, and brings a smile to every vicar’s lips. Hop shoots in spring are an intriguing answer to asparagus; and they’re great in softer cheese; but for me they are best in that four letter word, my favourite, ‘beer’.

CLEVERLY HOPPED BEERS

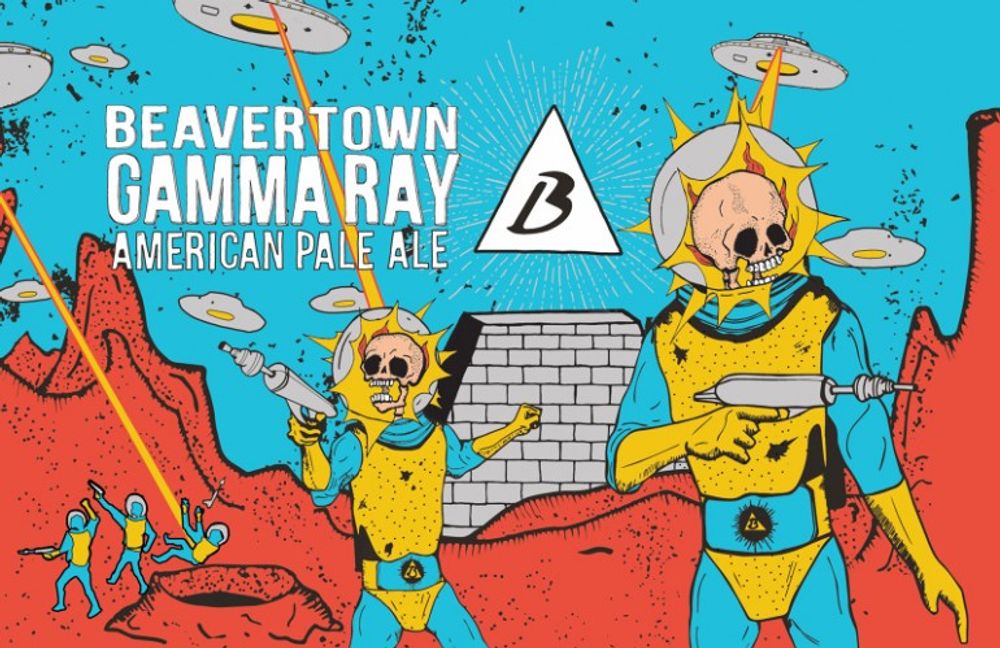

An IPA for the modern craft beer hipster

Worthington White Shield (5.6%) – a legendary IPA from Burton. Meantime IPA ( 7.4%) – a deep throated wonder; ages beautifully; Duvel Tripel Hop (9.5%) – the in-ya-face racy Sauvignon Blanc of beer; Beavertown Gamma Ray (5.4%) – hops played like the tappets of an Italian car engine.

HOP NERDS HOP OIL PLAYGROUND

As you have read this far, here’s a little added value treat for you as Simon Yates, master brewer at Marston’s brewery, shares his insights on hop oils.

- Myrcene yields flavours that were not traditionally considered desirable by European brewers, and noble hops are very low in myrcene. However, many American hop varieties are very high in myrcene; it makes up up to 60% of total oil in Cascade and up to 70% in Amarillo. Also found in some citrus fruits, myrcene lends American hops many of their distinctive flavours.

- Humulene is not closely related to bitterness. It provides much more to the woody organic flavour of a beer. It is linked to the spice in coriander, and thus produce a spicy flavour over long boils or mash.

- Caryophyllene’s fragrance is obvious when you split open a hops cone and has essence of a dry woody, spicy, earthy bouquet. Its smell can be sweet, and its link with the clove plant becomes apparent when you compare the two. Caryophyllene provides a lot to the character to what we know as ‘hoppy’ aroma. The fragrance oxidizes quickly when exposed to oxygen, and this diminishing return for the senses is evident when handling older or aged hops cones.

- Farnesene is also used widely in the perfume industry due to its beautiful smell. It is also used in masks and powders. Farnesene’s fragrance has been compared to that of magnolia flowers and having citrusy notes with green, woody, vegetative odor with hints of lavender. Its contribution to beer is significant for aromatic qualities.