For years wine producers’ export books would have been full of buyers from the same countries that they could rely on to buy their wines. In the future they will be increasingly turning to new buyers in different countries thanks to free trade agreements signed between their countries.

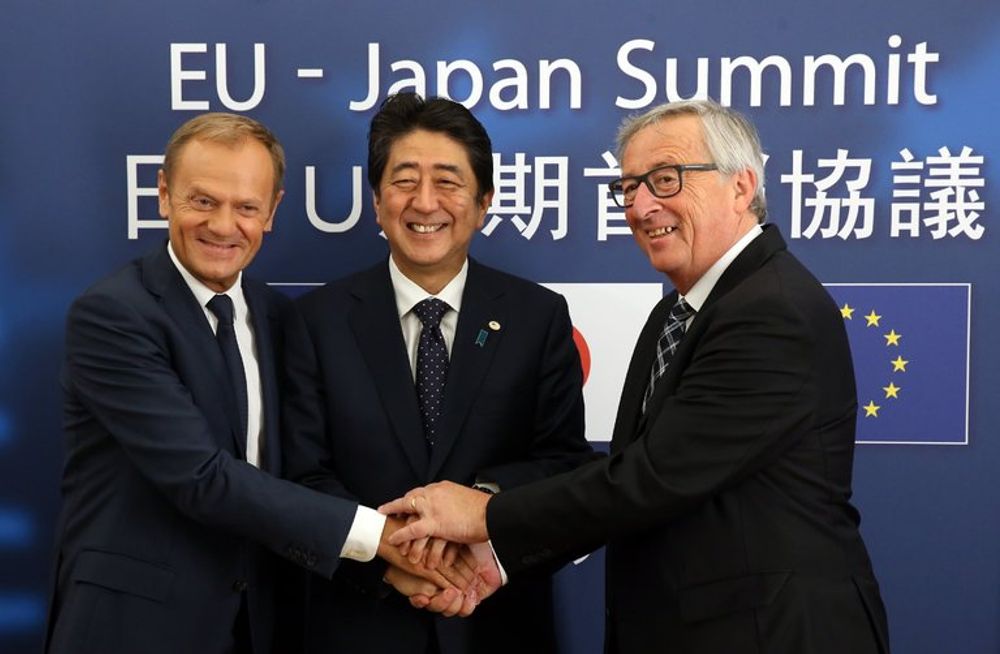

Of all the headline making news photographs you would have seen as part of the end of the year quizzes and round-ups in the national press, here’s one picture that would probably have not made the cut.

Three very happy politicians agreeing what is the EU’s biggest trade deal with any country – Japan.

Yes, a couple of those individuals are more than just a bit familiar to us. In fact Donald Tusk, president of the European Council and Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commisson, were on our TV screens as much as Ant and Dec in 2017.

But here, for once, they are photographed smiling – not with Theresa May – but crucially someone they have been able to do business with. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan, as they shake hands on arguably one of the most significant business deals of not just the last 12 months, but any 12 months.

The Free Trade Agreement signed between Japan and the EU is exactly the sort of agreement the UK government pines for the other side of Brexit.

It is also the biggest bilateral agreement signed by the EU with any independent country. A deal so big that Japan and the EU claim the FTA will create the biggest economic area in the world accounting for nearly a third (30%) of the world’s GDP. No wonder Tusk and Juncker look like they have atickling stick between them.

Those smiles will no doubt turn to scowls whenever the Brexit negotiations get under way again. But the agreement with Japan is a further indication of how,quietly but surely, and often away from the glare of the TV cameras (particularly in the UK) the map of power is changing around the world.

It has, for example, at a (four year) stroke opened up free trade for all wine producers across Europe with what is currently the EU’s fifth biggest export market for wine. But we can expect it to become a lot more important than that in the coming years.

Deal or no deal

Which brings us to one big positive for the global wine market going in to 2018. The emergence of an increasing number of Free Trade Agreements between traditional wine producing countries and emerging consumer markets. Deals that will quietly, but very surely, changing the short to mid to long term dynamics of the global wine market far more than the ups and downs of this year’s global wine harvest compared to the last

Now FTAs are hardly something new, but for those of us that have been following the Brexit negotiations closely, we are now far more aware of who has trade agreements in place with each other than we ever were before.

The impact for countries that are able to strike FTAs between themselves can be enormous, and almost instantaneous. Particularly for those looking in to make bigger inroads in to the economic powerhouse of Asia, and China, in particular.

China and Australia’s trade deal may have been a long time coming but is having a massive impact on business between the two countries

China now accounts for 30% of Australia’s total global wine exports thanks to the roll out of an FTA agreement signed between the two countries in December 2015.

The deal saw tariffs on imported Australian wines reduced from 14% to 11.2%, and then by a further 2.8% on January 1 every year until it reaches zero in 2019.

It means China has replaced the US as Australia’s biggest market and in the year to September 2017 exports to China were up 56% to a record AU$739. If you factor in Hong Kong and Macau then value exports to Greater China were up 42% to AU$853 million. Dwarfing the US in second place with AU$461m.

Australia even outsold France in October to become the biggest exporter of bottled wine to China by value, with 8.42 million litres, worth US$69.6m, compared to US$63.7m of bottled French wine, and 12.89 million litres, according to the latest figures from the China Association for Imports and Exports of Wine & Spirits.

The two countries estimate overall trade across all sectors between the two countries has increased 4.4 times since the initial FTA was signed in 2005.

Made in Chile

Chilean wine is now booming in China on the back of its free trade deal

Chile’s global export wine strategy has been turned on its head since the full impact of an FTA with China has come in to effect since 2015. That was the year when final wine tariffs were removed, resulting in a 13% increase in the value of Chilean wine exports to China in 2016, with even more expected from the final year figures in 2017.

China has now replaced the US as Chile’s biggest wine market, exporting $195 million worth of bottled wines to China in 2016, compared to $183m to the US. The UK remains third at $148m.

But as we are slowly learning from our Brexit experiences, FTAs don’t happen over night. Chile and China, for example, first agreed an FTA in 2005, but it was some 10 years later before the final tariffs on wine were removed.

So the rewards are there, you might just have to be patient to get them.

Global discrepancies

It means all around the world we are seeing huge discrepancies on which countries’ wines are being exported and imported thanks to these trade deals.

Georgia, for example, no longer has to worry quite as much about losing out on sales to Russia now that it too has a highly lucrative FTA with China that will see its tariff reduced from a staggering 93.9% to zero.

It also means the fate and future of some wine countries are going to become increasingly embroiled in the political stance of their government.

US President Donald Trump has threatened to pull out of the NAFTA agreement with Canada and Mexico

Countries, for example, that would be usually falling over themselves to sign FTAs with the US are now having to switch their focus firmly to other parts of the world because of the protectionist policies of President Trump to opening up its borders to any more imported goods.

There are even fears that he could pull the plug on the NAFTA three country agreement that has been in place between Canada, the US and Mexico since 1994.

In fact Canada, more so than the US, will become an increasingly more important market once the agreed FTA with the EU is ratified by both sides, removing tariffs on 98% of products being imported.

Then there’s Brexit…

All these deals, and others, are taking place before we even get the chance to consider the potential fall-out from the UK leaving the EU at the end of March 2019.

The worry for the UK is that with so many FTAs being signed by those countries that it relies on so heavily for its wine imports with other potentially bigger, and closer markets to deal with, then it risks falling down not only the international wine export pecking order, but it is not able to put in place trade agreements to match when it is free to do so.

So when it comes to plotting, planning and sourcing wine in the years to come, wine buyers are going to be battling the diplomats and bureaucrats that are putting these FTAs together as much as they are fellow buyers in what are becoming more competitive markets to trade against, thanks to the trade manoeuvrings behind the scenes.

In fact you could argue the dynamics of the global wine market will be dictated more by which FTAs are in place between different wine countries than the individual demands from different countries for particular styles of wine. The UK, for example, may well be crying out for more Argentine Malbec or Chilean Sauvignon Blanc down the line, but if producers in those countries can get free trade deals with other countries closer to home, then it is going to take a lot of persuading to make them free up enough stock to supply a country it does not have a FTA with.