Christina Rasmussen tastes and fully reports on 14 Zwölberich wines, including a TBA that is “one of those moments where you wish time would stand still for a moment so you could imprint the glass onto your memory.”

At the very start of my wine career in London, I met the cheery and eccentric Richard Dudley Craig, who was perhaps the first person to kick-start my intrigue for wines outside of the norm, wines that eschew chemicals and stay true to their roots and their soils. His portfolio encompasses many biodynamic, organic and indigenous varietal gems. If you don’t know him, you should.

Dudley Craig Wines introduced me to Hartmut Heinz, the winemaker and owner of Zwölberich, a softly spoken and deeply humble man, who was one of the first handful of people to work biodynamically for the purpose of wine/ alcohol production in Germany, and the first in the Nahe. I am unsure whether it is due to his immense respect and understanding of nature and his land, but he has one of the most calming auras I have come across. People like this are few and far between.

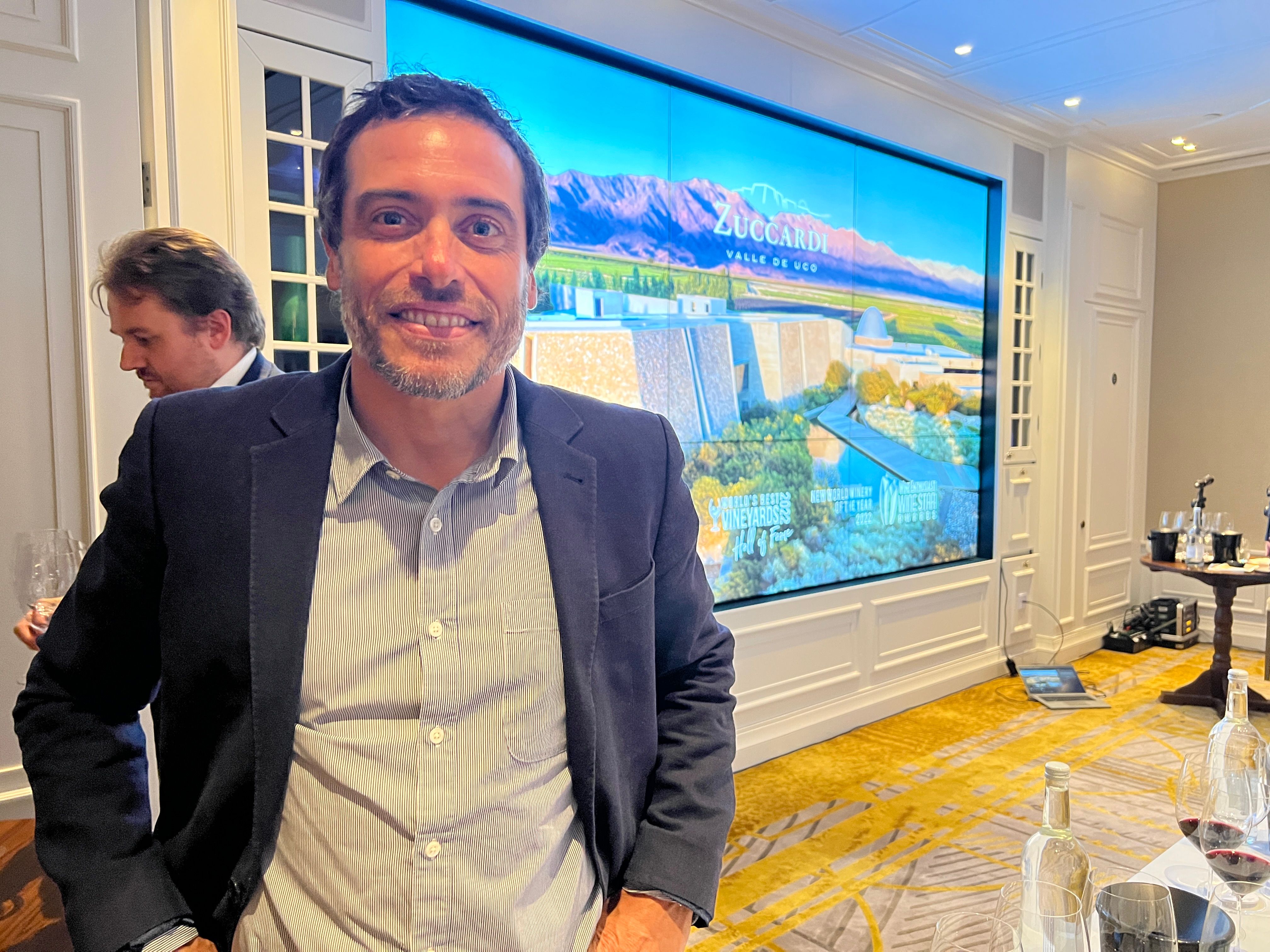

Hartmut Heinz, La Trompette, London, May, 2018

No small project

The Zwölberich estate is not small. Hartmut farms 33 hectares of 16 grape varieties (with three hectares recovering and being replanted), with an annual production of 250,000 bottles a year. Dependent on the vintage conditions, there are usually an astounding 40 to 50 cuvees, to ensure maximum terroir expression. He is a leading example of how biodynamics can be possible on a larger scale, and indeed minimal intervention winemaking with indigenous yeasts and low sulphur additions throughout all wines.

It was Hartmut’s father who began the basics for biodynamics, through planting cover crops amongst the vines back in 1956. Without knowing about biodynamics, he was entirely convinced that a green soil was a better soil. By using hands, he could feel that the soil was more alive, although he was afraid of eschewing spraying completely as this was so against the norm. It was Hartmut who converted the entire estate to organics in 1987, which was a relatively smooth process. Hartmut recollects, “Without having such a healthy soil the change to organics and biodynamics would not have been so easy.”

Hartmut married in 1985, and had his first son in 1986. This led to natural discussions about what to eat and drink, which led to organics. “It was right after Chernobyl, people could see how fragile our ecosystems were and it changed everything for us. What I wanted for my family had to be the same as for my work. Our neighbours, however, did not understand.”

Early influences were the Dottenfelder Hof farm, which helped Hartmut greatly at the beginning with explanations of how to farm biodynamically and gave advice with regards to horns and seeds.

One of his earliest biodynamics vinous influencers was Jean-Pierre Frick, who he met in 1987. By this point I beam, Frick is one of my wine heroes, whose book du vin de l’air has enormously influenced my own outlook on grape growing and wine production.

Biodynamics & sense

Speaking about biodynamics, I asked whether there was one aspect in particular which boosts the ecosystem of the vineyards.

“With biodynamics, you’re either 100% dedicated or not. The work comes together from different powers; it is not possible to leave one aspect out. We apply all preparations three times a year, but the effect on the entire estate only comes from working biodynamically for many years – it takes five to seven years to really see the effects.”

“There were many things I didn’t understand at first – 50g of a powder with 40L of water for an entire hectare?! – It is difficult to come to terms with, but it works.”

With his calm, sensible approach, Hartmut emphasised that he only carries our actions in the vineyard that are good “for the vineyard, or for the people.” At the start of his experiments, in 1990, he divided one vineyard into seven parcels, and within those seven parcels treated three rows with the preparations and three without. Within the first year he could already see a difference; although the sugar and acidity differences in the actual grapes was still very small, by looking at the plant there was great evidence. On the unsprayed rows, on hot and dry days the grapes would hang down and appear withered, whereas on the sprayed rows the leaves and bunches were fresher and healthier.

“These were the signs to me that it works.”

He began with 12 hectares, and has always tried to have complete squares with no neighbours to create complete ecosystems, with bushes planted to protect the vines. It is difficult to work biodynamically with no interference at all from neighbouring vineyards and chemicals.

Hartmut contemplated, “We do our work under the same sky as our neighbours; the wind does blow. Even if we built a glasshouse, the soils are still connected to the soils of other places. Water does not ask where it can go.”

The wines, with anecdotes…

Riesling Sekt Brut NV (labelled NV although actually 2014 vintage. Secondary fermentation in stainless steel, aged for two years in stainless steel and bottled under pressure. 85g of Riesling juice added. Tiny amount of sulphur only before bottling.)

Bright, clean, classic Riesling nose. So fresh, with charred lemon rind meets fresh tarmac and lemon juice notes, with some blossom pollen hints. Lovely depth and oh-so drinkable, full of life and texture, with a waxy finish. So moreish and such a crowd pleaser.

Brut Royal zero dosage NV (From 2011. Champenois method with indigenous yeasts added from other fermentations to restart fermentation for secondary fermentation. Five years on the lees, disgorged in October 2017. 60% Pinot Gris, 40% Riesling.)

The nose shows grapefruit pith together with waxy honey notes, apricot skin and fresh honeycomb. The oxymoron of tight-wound creaminess applies here, but this is possible, as complexity and extended lees contact meets the mystery of the energy found in biodynamic wines. A very calm wine, it is self-assured. Incredible length and very complex.

Harmut encourages us to leave some wine to come back to.

“Wines need to breathe and open. We have such little understanding for aged wines. Our lives are in such a hurry but the wines can teach us to slow down, and to calm down.”

Zwölbericco Secco Rosé NV (From Portugieser, which has less natural colour. Direct press of grapes from a young vineyard.)

Pithy cranberry skin notes, with a distinct salinity on the mid-palate and a surprisingly bold body with some currant notes. Refreshing, juicy and delicious.

Before moving onto the whites, Harmut expresses the importance of vine age.

“We are lucky to have old vines on the property. My father always believed in letting vines age. Some of our Riesling was planted in the 60s, and our Pinot Blanc, Gris and Auxerrois were planted in 1985. Older vines are much healthier than younger – there are lower yields but the quality is much higher.”

“The older the plant, the more complexity. This, combined with ageing on the lees, means the wines come into themselves. They may need time to develop but they are very stable.”

Auxerrois 2016

Hartmut’s father was responsible for the elevation of Auxerrois from table wine to Qualitatswein status. He was seeking minerality, and wanted to find a grape variety that had a less intense nose than Pinot Blanc, and a less intense body than Pinot Gris. He found this in Auxerrois. With 2000 votes from the population via pen and paper in the 80s, it was upgraded to a Qualitatswein.

Pretty fresh green melon pips, juicy with white peach juice and melon juice with a poised, lifted palate. A “whoomph” of minerality hits on the finish, with such freshness and a mouth coating energy left on the finish.

Weissburgunder feinherb 2017

This didn’t quite finish fermentation, but Hartmut left it that way. He smiled and noted, “the heart of the grower lets the wine go as it likes.”

Almost silver in colour, this feels wonderfully balanced. Straight, bold and direct, with a rainwater-like minerality. Plush yet fresh, silky and so delicious.

Spätburgunder Rosé 2017

Undeniably Pinot Noir; so comfortable in its variety. If this was room temperature and we were blindfolded – this is a rosé with such character that I am sure it would fool many. Cherry flesh, fresh moss, mandarins and that mirrored dense energy. So much more than what many perceive Pinot rosé to be.

Riesling Langenlonsheimer Löhrer Berg “Genesis” Kabinett 2016 (From the top of the hillsides at 280m altitude, this vineyard was planted at the start of the 90s. The poor soils consist of 30 million year old beach sediment; very sandy with remnants of oyster shells and fossils.)

A singing nose of yellow tulips, white flowers and subtle fresh grass; not unlike having your nose in a wild meadow. Very fresh and pure and true to Riesling in a delicate format.

Riesling Langenlonsheimer Steinchen “Alte Reben” 2016 (From the south side of the hill – younger soils with more hummus. Old vines.)

Prominent wet stone notes; reminiscent of the smell of rain on pavement on a hot summer’s day. Crushed herbs on the palate, with fennel notes and delicate damp undergrowth.

Auxerrois Rosenteich “Alte Reben” 2016 (Planted in 1958, from suitcase cuttings from Luxembourg. The Rosen vineyard is an “oasis for biodynamics” as it has no neighbours, only a forest, a museum and apple trees).

Intense, heady nose of yellow apples, fresh pear, apricot skin and even blackcurrant skin. Orange rind on the palate, with a beautifully driven opulence. There is even a hint of raspberry juice here. A fascinating wine that blends poise with body and depth with a finish that goes on forever. It gives to the palate one of the silkiest textures I have ever experienced in a wine.

Regent 2015 (planted on slopes in 1993. Regent is very resistant to mildew.)

Dense, wet earth nose. Packed full of bright black fruit on the palate, notably blackcurrants, with spice, cardamom and black pepper notes. Slightly reductive in a positive way lending freshness, with baked earth notes on the finish.

Spätburgunder Spätlese Langenlonsheimer Steinchen 2015 (harvested late, three week ferment. A selection of the best bunches stay in the vineyard for 2-3 weeks longer. 50% Mariafeld and 50% French clones. Aged in German oak – once Hartmut discovered that the keeper of this forest sold his oak to France, he stopped buying French oak and only bought German. Barrels are in 1200L and 2400L formats.)

The nose is like walking through the forest in mid winter. Subtle earth, lilac oil and wet vegetal notes with fresh earth and such a seductive, pretty side. Black cherry skin meets a wild side but with such purity and length.

Dornfelder 2016

Hartmut interjects, “us Germans, we had to learn how to make red wines. The 1980s saw us introduce the crossings to make red wines with colour; it was banned in 1971 to use Spanish red wines for colour.”

Wet earth, cracked black pepper, plums and sour cherries, with a velvety mouthfeel and a lingering finish of peonies in rain.

Riesling Guldentaler Rosenteich Auslese 2011

Pollen, tree sap, caramelised peaches, ripe apples, nectarines and subtle rubber notes. Shimmering body and a gentle mouth-coating texture, with electric energy and a mineral finish.

Riesling Guldentaler Rosenteich Trockenbeerenauslese 2003

Wow. One of those moments where you wish time would stand still for a moment so you could imprint the glass onto your memory. Such a special wine, one that is fairly impossible to encapsulate on paper. Heady, earthy apricots on a summer’s day in a field full of dried hay; ethereal and somewhat time defying.

La Trompette’s pairings portrayed German wine’s versatility with food: everything from pecorino, asparagus, garlic leaf and sea herbs wound their way perfectly into the structured, lively web of the wines.

And for the future?

Global warming has begun to play a factor. They have planted some vines on the North sides of our vineyards for the first time.

Hartmut also hopes to introduce more animals to the vineyards. He already has wonderful wildlife there, but he wishes to find one farmer to come into this little ecosystem to manage his or her livestock there. He would love to have horses, but for a vineyard of this size, this remains a dream for now

And to finish…

As I sit reading about the estate, I come across a couple of the Zwölberich mottos… “To foster the vitality and health of the vine in harmony with nature is our passion, our creed and our way, for the joy and benefit of the people… For us, a lot of good wines feel at home, simply because the vines are at home in our family.” Excuse me while my heart melts a little bit. That’s what wine is about, isn’t it? It’s not about putting a number down on paper. It’s about finding wine that connects land with emotion: wine that has the capacity to tug at your heartstrings and that inspires you to visualise a place.