“Amarone will always be Amarone, a ‘Marmite wine’ for some maybe, but a wine with a distinctive following that seems unlikely to go away, irrespective of any stylistic changes,” writes Keay.

The Cesari clan at Brigaldara: Stefano, Maria Gilla, Lamberto and Antonio

There was a time when wine drinkers wanting a full-bodied red could be confident about where to find it. Argentinian Malbec, Barossa Shiraz, Rioja, Ribera del Duero and Priorat were all pretty much safe bets for high alcohol wines, many with low acidity and strong and dark enough to sustain you on even the coldest night.

But the shift towards lighter, lower alcohol, acidity-driven wines – as producers focus more on elegance, balance and grapes grown at higher elevations – has made finding a classic barnstorming red more of a challenge.

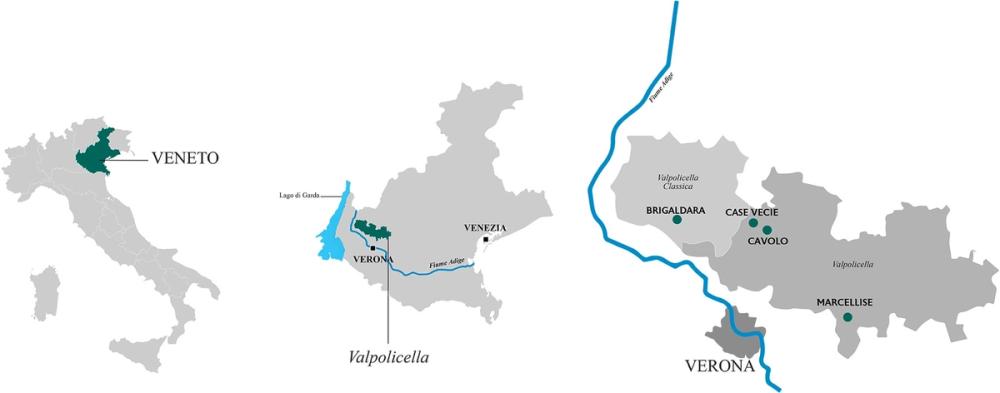

Valpolicella was once a region reliably assured of producing hefty Amarone wines with alcohol levels of up to 17% and for many, the ultimate winter wine, but this too is changing its image.

“Although consumers in the far east still like a big Amarone – and also some in the US – people in Europe are definitely drinking lighter and the wines we make reflect this,” says Stefano Cesari owner of Brigaldara, a 50 ha producer which makes Amarone – and Valpolicella, and Ripasso – in roughly equal amounts. One of the original 12 Families of Amarone, it made its first vintage back in the early 1980s (volume today is around 300,000).

Amarone the old fashioned way: Stefano Cesari

Cesari says that he has always made Amarone the old-fashioned way by drying grapes on open air racks within months of harvest rather than in plastic crates in temperature-controlled warehouses; he has also ensured that most of the fruit are high altitude grapes.

“Our philosophy has always been not to be too full-bodied and oaky, particularly with Amarone, whilst Valpolicella should be light and reflect the site from which the grapes come,” he says, adding that grapes from the hills have freshness even when fermented up to 16% alcohol.

Cesari argues that extensive use of inferior quality grapes has impacted on the reputation of Amarone and encouraged some consumers to turn away from the style.

“Too many of the Amarone on the market today are made from bad grapes grown on the plain, with added sugar,” he complains adding that many are sold for around €10, further devaluing Amarone’s reputation.

According to Cesari, the problem has become acute with the huge expansion in Amarone production in recent years, from around 4m bottles in the 1970s to around 9m in 2000 to some 18m today, almost as much as the volume of Valpolicella produced in the region (around 20m bottles with 36m bottles of Ripasso as well); the region’s four cooperatives control some 65% of the market.

“As a DOCG we should be looking to sell 10m bottles of really high-quality wine rather than 18m bottles of wine including all this average/inferior stuff,” he says.

Cesari’s three Amarone very much express this preoccupation with site:

Cavolo Amarone comes from this warm valley, surrounded by olive groves

- Cavolo is aimed at being easy drinking despite its 16% alcohol made from grapes (59% Corviona, 21% Corvinone, 17% Rondinella and 3% others) taken from a 150m high east facing slope;

- Classico from a west facing slope which gets the full advantage of the afternoon and evening sun, is heftier, with bright red cherry notes and other red fruit;

- Case Vecie is a very different beast, made from grapes (39% Corvina, 30% Corvinone and 31% Rondinella) grown at 450m which means they “mature more from light than temperature”; it has long maturation spending like Cavolo some two years in small wooden barrels and then another two in large wooden barrels; herbal, floral and cranberry notes come through in a long complex finish. What one might call a ‘meditation wine’, certainly very nuanced and a long way from the hefty wines many have come to associate with Amarone. All have r/s of 2.5 g/l or less – well below the 9 g/l allowed under Amarone regulations.

Brigaldara’s Valpolicella

Cesari’s focus on vineyard site and producing quality grapes extends to his Valpolicella wines on which he clearly aims to focus on more going forward, arguing that the wine – which managed to acquire a bad reputation with excessive yields – is very undervalued by consumers who tend to bypass it for richer and fuller-bodied Amarone and Ripasso.

“Valpolicella is something people can drink by the bottle whilst Amarone is something they drink by the glass,” he says.

Again, the Case Vecie is lightness itself, made without appassimento whilst Brigaldara’s other Valpolicella is also light, belying its 13% alcohol, and clearly site-driven.

“The future for all our wines is going back towards lightness, quality and expression of the varieties,” he says, emphasising that the Corvina and Corvinone and Rondinella that grow here are of the highest quality.

Cesari adds that, because the Corvina in the Valpolicella area is a different clone to that which grows for Bardolino on the shores of Lake Garda, there is no risk of his lighter style of Valpolicella being confused with Bardolino.

“Our yields are much lower than in Bardolino whilst the wines there are lighter in colour, that region’s volcanic soils giving a very different expression,” he says.

Cesari argues that the wine world now increasingly takes Valpolicella seriously as a wine style, “something akin perhaps to Pinot Noir”, and that the negative connotations many had of the wines in the past has receded. But he agrees more work needs to be done in updating and upgrading Amarone’s image.

“I think we do need to work to change the image and get away from the association of being a heavy, sweetish high alcohol wine, especially as these seem to increasingly be out of fashion,” he says.

He notes that he is not alone in his approach with other producers also making the “lighter style” including Allegrini, Bertani and Ca la Bionda. In fact, the process seems to have started back in the 2010s according to Italian wine writer, Walter Speller, in the latest fifth edition of the Oxford Companion to Wine, reminding the reader that Amarone is actually not only quite a new wine – production only started in the 1950s – but an accidental one too.

“Strictly speaking Amarone is a recioto scapata, literally a recioto that has escaped and fermented to full dryness when the intention was to make a sweet wine,” he says.

The trend towards less hefty Amarone has clearly accelerated with younger producers coming forward, attuned to the current state of the market which favours lighter, less oaked wines but also amongst the more established winemakers who recognise the market has moved on.

“We’ve changed a lot and want to make wines defined by elegance, with fruity, balsamic notes rather than an excessive appassimento style,” says Franciso Allegrini, showing his family’s wines at this year’s Liberty Wines tasting.

“Our vineyards are east facing and located at 500m which means light, maybe even more than heat, plays the key role in the maturation of the wines.”

“Our winemaking approach ensures that Amarone remains a special occasion wine.”

Is Amarone’s future bright?

So what does the future hold for Amarone, given these trends? Allegrini says the more approachable style is popular in most markets – aside from northern Europe where the older big style retains a loyal following – and says consumers appreciate forceful wines that are not too powerful.

Cesari has been selling Brigaldara steadily through Vinum Terra for the past 30 years but admits the UK hasn’t been a good market because some wine consumers simply find it too expensive.

“Our winemaking approach ensures that Amarone remains a special occasion wine with prices that reflect this and the fact that twice as many grapes – some two kilos – are needed to make one bottle of Amarone, compared to a bottle of Valpolicella,” he says.

But perhaps at the end of the day that is what Amarone is – a special wine, defined by the region it comes from and the grapes that go to make it. Amarone will always be Amarone, a ‘Marmite wine’ for some maybe, but a wine with a distinctive following that seems unlikely to go away, irrespective of any stylistic changes.