“Germany should move to a provenance-based appellation system that distinguishes between regional, village and single-site wines; it should also define the Prädikate better and restrict them to certain grape varieties and regions,” says Krebiehl.

Peter Dean – So Anne, can you tell us where has German wine been? where is it now and where is it heading?

Anne Krebiehl MW – German wine, at least in the second half of the 20thcentury, has been in the doldrums. Home-made doldrums, one must admit, but somehow the Germans are very good at dwelling on them.

There are parallels to other European regions – say Chianti or Soave – which became as much a victim of their initial success but somehow the Germans took longer to emerge with real quality.

Since the turn of the millennium Germany has been on a roll with an unprecedented density of quality production and a new-found focus on what makes Germany unique. The direction of travel is exciting as the latest generation of winemakers are re-defining what German wine is in the 21stcentury.

PD – Why is now the right time to re-evaluate the importance of German wines?

AK – The right time is now because so much has happened. The quality revolution began very slowly and tentatively in the mid- to late 1980s, gained real momentum in the 1990s and is now in the hands of a new generation that came of age just as that new quality paradigm was taking shape. They have a completely different understanding of what they are doing and aiming for than even their pioneering parents had.

The parents set out to prove that quality was possible in an almost hostile marketplace, even at home, the youngsters today no longer have to prove that, they can now shape and hone what variety, region and site express.

Ahr vineyards in winter; Rivers and slopes are important in most wine regions but in Germany they completely define viticulture

PD – Do you think that its reputation as a ‘sweet plonk producer’ was of its own making?

AK – Absolutely. During my research it was interesting to trace how the law itself enabled this to happen, even encouraged it. There are some scathing articles from the 1960s onwards that pillory this approach. Piecing together what happened in the late 1960s, the 1970s and 80s was fascinating detective work: all the federal laws are online and their evolution can be studied, but a lot of the regulations based on the 1971 wine law were devolved to the federal states.

Piecing this together was harder – but enlightening. In the years 1969-1971 the idea of “quality” was linked solely to grape ripeness and an already fudged definition of origin was supposedly put right – but opened the door for even more shenanigans. Bit by bit sweetness caps were abandoned.

Speaking to older winemakers who lived through that transition also provided perspective – I think it is important to see events not only through today’s prism but also in their contemporary context. The Germans put so much faith in technical prowess, in engineering, in progress – and honestly believed that an incredibly fragmented producer base could be hauled into a brave new future with that approach, legal loopholes notwithstanding.

What is interesting is that Germany made its quality revolution despite the law. Climate change also plays a huge part: from the 1950s to the late 1980s Germany did not have a climate which would reliably ripen grapes in every vintage (but then neither did Burgundy). The dry Rieslings as we know them today would not have been possible then – there were some horror vintages with 20g/l and more acidity in must!

PD – How has that been addressed?

AK – While the law has not really changed, climate has. So has education, approach, outlook, mindset, viticulture and winemaking. Today grapes ripen in every region. Wine today is made to express variety, region and site – and producing cheap plonk has been left to others who can produce it much more efficiently than Germany with its expensive land, high wages and red tape.

Not to say that there still isn’t cheap wine: there is – but even that bears no resemblance to the derided “sugar water” of the past. Sales of sweet plonk are thankfully in terminal decline because survival in the wine industry is only possible if there is a market for the wines. The producers and co-ops still following that outdated model are struggling.

Snow in the Schlossböckelheimer Kupfergrube, Nahe

PD – Has the market for German wines changed in the UK?

AK – I think the change over the past five years has been immense. You used to have to go to a specialist importer to get your hands on Spätburgunder, i.e. Pinot Noir, today it can be found on (some) supermarket shelves. Importers who used to have one token German wine have broadened their offer. And thankfully Germany – while still and rightly being equated with Riesling – no longer stands for just that one variety.

Nuanced, bone-dry Weissburgunder (Pinot Blanc) is a real winner, as is Germany’s style of Grauburgunder – pitched right between the (mostly) rather neutral north-Italian styles and the rounder Alsace styles. The big winner of course is Spätburgunder. But I am becoming an ever greater fan of Silvaner, especially from Franken, and I would also suggest that people try Lemberger and Trollinger. I am also hoping that Sekt, German sparkling wine, will win hearts and minds.

PD – And talking of style… German wine, and it is not unique here, seems hellishly complicated to navigate – why is this? and what do you think should be done to simplify things?

AK – One of the reasons people are so confused is the clunky, complicated law combined with the German language. That is why it is so hard to get your head around it all. Most students end up more confused than enlightened. But I must also say that often even the people who teach German wine do not fully understand the implications of the law (see below) so what chance have students got, let alone consumers?

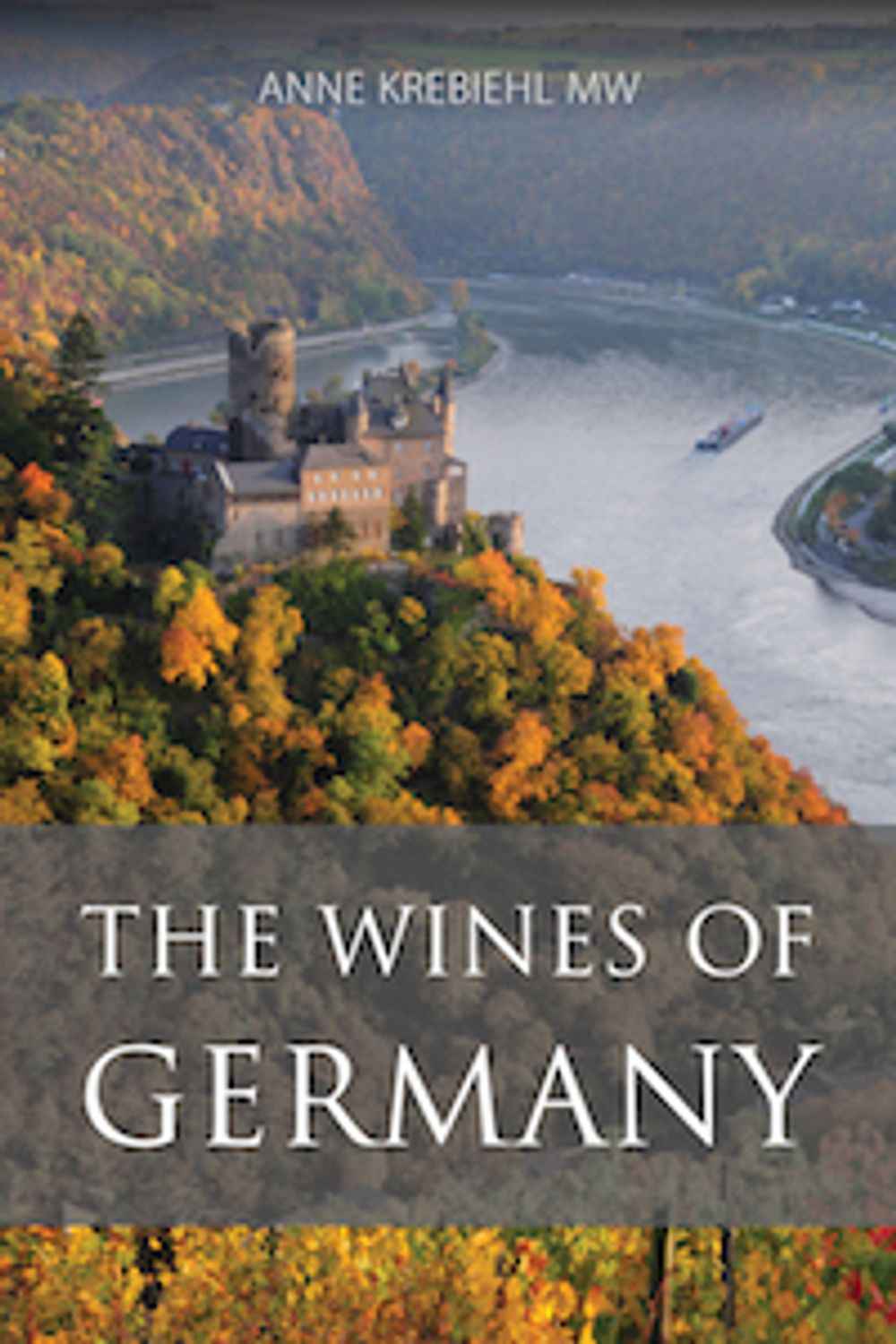

But before I address this, the elephant in the room is staring me right in the face: I got to write a book on all of Germany – yes, 13 very different regions across four degrees of latitude with fundamentally different histories and cultures. Who would dare to do this to France and Italy?

Sure, hectarage-wise there is some justification but not culturally. Just imagine the impossibility of all of France or all of Italy having one law, equally applicable to all regions and climates – that is the case in Germany. And this is what every wine student struggles with: Germany is so diverse but all the regions are always lumped together.

People still teach the dreaded Prädikate as though they were a quality ladder when in fact they are a ripeness ladder. Since Prädikate are defined only by minimum but not maximum ripeness levels, thousands of students have been shown “Kabinett” wines that in style are in fact “Spätlesen” – with straight-faced teachers earnestly and uncritically explaining “style” just because a wine is labelled as “Kabinett” – ouch!

What should be done to simplify this? The easy answer is that Germany should move to a provenance-based appellation system that distinguishes between regional, village and single-site wines; it should also define the Prädikate better and restrict them to certain grape varieties and regions. I have seen a 14.5% ABV Kabinett Spätburgunder from a Baden co-op – and that just makes my head hurt with its utter travesty.

Some movements are underway at legal reform – but what can be done now is that those who teach German wines, and those who deal with German wines should educate themselves properly and understand what is actually the case and what not. My book will help them do this.

Hanspeter Ziereisen descending into his cellar

PD – Is diversity a blessing or a curse?

AK – Ah – I spot a wide-ranging philosophical question here! In terms of wine, it can only be answered one way: it depends on the target market and consumer.

I personally believe that diversity is good, that variety is the spice of life, that detail is sexy. That diversity creates confusion is a given, but not only in wine, and all of us who have been bitten by the wine bug revel in this diversity: how a thousand different Pinot Noirs can all be Pinot Noir yet be subtly or strikingly different. What is not to like?

Those who shy away from this diversity still have the possibility of enjoying countless brands of well-made, delicious wine. The market caters to us all and you no longer have to be a connoisseur to drink well. And before you attack me for this: has humanity ever had such a wide choice of well-made, clean wines?

PD – Name three areas that you believe German wine is making greatest strides in and why?

AK – 1. Sekt– as regular readers will know; fizz is close to my heart. Sekt was the last bastion of German wine to be given the quality treatment. In the 1960s and 70s a once thriving industry succumbed wholesale to mass-production of tank-fermented, easy Sekt and gave the once luxus-denoting term its tainted image. This is no longer the case: there is now world-class traditional method Sekt – still small in production but it does exist.

This is where Germany has made the largest strides, especially in the past five years. The best thing about it: the very best bottles are still slumbering away in cool cellars, maturing on their lees.

Rieslingsekt, in various styles, is a USP – something the world needs to learn about.

2. Elegance & Identity – It used to be true that Germany was a cool climate country. Some of its regions are still cool (Saar, Nahe, Saale-Unstrut) but the really cool climate has moved on (hello England!). Nonetheless, when Germany first tried its quality game, winemakers were still chasing power, they thought more was more: more ripeness, more volume, more oak – both in red and white.

The first GGs (Grosse Gewächse, the top dry wines from classified single vineyards) in the early 2000s had some monsters among them. Today the tide has largely turned: the best winemakers today look for grace, freshness and depth rather than power – and today’s climate allows them to do that. This is a direct result of a newfound, more self-confident identity that was almost obliterated by two world wars and the disastrous legal framework of the 1970s and its unintended consequences. This goes for Riesling, Spätburgunder and Lemberger and brings forth some of Germany’s most beguiling wines yet.

3. Climate change – As things stand today, Germany is still largely a beneficiary of climate change. However, the hot summers of 2017, 2018 and some heat spikes in 2019 have given everyone a true and undeniable taste of a possible future.

Today the climate change discussion is often framed in terms of grape variety. Some people have suggested that Riesling as we know it will be a thing of the past. Well, I for one am glad that the meagre, unripe Rieslings of the 1980s are a thing of the past! In a country whose viticultural history was defined entirely by the ability to ripen grapes, where every viticultural measure was designed to achieve ripeness, where Oechsle were fetishised, there is a lot of scope for dialling these measures back, for adopting a different viticultural approach, for adapting to changed circumstances. The best winemakers are already doing that. And the dry Rieslings have never been better or more scintillating. That said, I have tasted some wonderful Viognier, some spicy Syrah. Even Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot ripen in some warmer soils. But the focus is and should be on Riesling, Silvaner and the grapes from the Pinot family.

PD – What do you mean when you write that Germany is now making ‘Riesling in its true form’?

AK – The kind of Riesling that made Germany’s reputation was long-aged, dry or just off-dry Rhine Riesling. In the late 19thcentury the playful, light and much more youthful Mosel and Saar Rieslings became equally revered. They were light in body but heavy on flavour – above all, they generally were not sweet. Because these wines were from the best sites, the best vintages and grown without artificial fertilisers, they had an inherent balance without being sweet. If they had a small amount of residual sugar, this was balanced by killer acid. [Only rare, nobly sweet Auslesen and Beeranauslesen were really sweet.].

The best comparison for historic Riesling styles in terms of sweetness would be Champagne which, until the turn of the millennium also had slightly higher brut dosages ranging between 10-15g/l. I leave you to draw your own conclusions about the fact that most Prosecco sold today is ‘extra-dry’.

The image of Riesling that was peddled in the second half of the 20thcentury is a distortion of what real Riesling really can be. We would also do well to bear in mind that the Kabinett-style, today often hailed as the quintessential Riesling style and often saddled with 40, 50, 60g/l and even more of residual sugar is not even 50 years old. When it comes to Riesling, perspective is all!

PD – Is German red wine its greatest secret weapon?

AK – I only wish it were! It is easy to drink well if you are in the know and have the necessary cash. The best German Pinot Noirs are no longer a secret, come with commensurate price tags and are sold alongside the other elite wines of the world.

What bugs me is that with almost 12,000ha of Spätburgunder, Germany is the world’s third-largest producer of Pinot Noir and yet there is no global brand of quality, go-to Pinot Noir from Germany. Being able to source from various soils and expositions, a clever winemaker could produce silky, sexy stuff year-in-year-out and make a real name for Germany – retailing at between £10-£13 – and then complement that with equally good Weissburgunder. I have no idea why especially some big co-ops are sitting on their hands. I am available to consult!

As regards the next-most planted variety, Dornfelder, I cannot find much joy in it. What excites me is Lemberger aka Blaufränkisch/Kekfrankos – and when well made even the misunderstood Trollinger can put a big smile on my face.

PD – A wine lover, has no prior experience of German wine… where should they start?

AK – They should start by examining their own preferences: What styles turn them on?

If they love international Chardonnay, they might want to look at some Weissburgunder GGs, if they love full-bodied reds they should try some mature Lemberger, if they love subtlety but recoil from too much acidity, Silvaner is just waiting to be discovered by them. If they like chillable reds they should go for an entry-level Pinot Noir or even a Trollinger, if they love fizz they should get a selection of Sekt. If they love inherent thrill, Riesling is their natural hunting ground.

Ideally, they would seek some professional help to do this: at their local independent, at a wine tasting event or at a bar/restaurant with a good BTG list.

Schlossböckelheimer Kupfergrube in summer

PD – What did you gain most from working harvests abroad

AK – My first harvest, in 2009 for Felton Road in Central Otago, New Zealand, was transformative. I had come away from the wrong career, was at a low ebb, lost really, and being very far away from everything familiar, doing something so real, so honest, so age-old as harvesting grapes was balm. My back never hurt and I took to it like a duck to water. Being outside all day alongside a wonderful team in such a wild landscape was amongst the most beautiful things I ever did.

It started a process of healing and gave me the confidence to stick with my new but precarious life in wine. [Huge thank you to Roger Jones for helping to arrange that and a huge thank you to Richard Siddle – the Chief – for allowing me to write about it.]

The same year I worked a harvest in Baden, Germany and was in both cellar and vineyard, the following year I worked a harvest in Barbaresco and was almost entirely in the cellar. These two harvests taught me the reality of winemaking, of logistics, of high volumes, of fruit quality, of early mornings and late nights. By then I had a lot more understanding of the winemaking process and I think I could not have passed my exams without having worked these harvests. In 2017 I put in just a few days on a steep Mosel vineyard – just to learn the true meaning of the term “Steilstlage.” But there is one thing above all that these stints taught me: respect for nature, farming and (good) winemaking.

PD – When you are not enjoying a glass of German wine what can we find you drinking at home and on holiday?

AK – Where to begin? Fizz of course – I am a great devotee of fine traditional-method sparkling wines, from Champagne, England, Alsace, Germany, Tassie, California…. There is always at least one bottle in the fridge. My love for dry Riesling and Pinot Noir extends well beyond German borders.

I also have a weakness for Styrian wines: Gelber Muskateller in summer, oaked Sauvignon Blanc in winter – and the other day I had a gorgeous Weissburgunder from there. Where reds are concerned, I look for translucency and acid: Sangiovese, Nebbiolo and the Nerellos are faves, as are more sinuous examples of Blaufränkisch. Some Syrahs are irresistible but there is so much out there that I don’t drink enough of, cru Beaujolais for instance…dry Lambrusco….

PD – Spirits?

AK – I used to be able to mix a pretty mean White Lady but these days are gone. I can no longer take spirits; I am under the table in no time at all. I might have a Campari Soda if nothing else is on offer, but a weak one. These days I use spirits to flavour fruit or desserts.

PD – When you are not immersed in the world of wine what do you enjoy doing?

AK – I like to be active during the day and chill in the evenings. Lounging around during the day drives me crazy, so I need to do something with my hands: gardening, cooking, baking, even tailoring. I love to move in water, to swim, to be outside, to hike. Books and records are always part of the deal – as are dear friends.