How far should the sector be leading the agenda on sustainability when the consumer demand is not necessarily there? Richard Siddle listens to the healthy debate at the Vinexposium ‘Act for Change’ Symposium.

What to do with consumer research when it does not come up with the answers you want or expecting? Go back and ask a different sample another question?

That was the uncomfortable conclusion to be drawn from a lively debate on the future of wine packaging at the recent Vinexposium “Act for Change’ Symposium in Bordeaux.

Lulie Halstead, chief executive of Wine Intelligence, was the one there in the uncomfortable position of having to burst the bubble of excitement around what is being done across the industry to be more sustainable, particularly around introducing ever more innovative packaging to wine.

She pointed to its Vinitrac research that shows that whilst there is a majority “connection” amongst consumers when it comes to sustainability -56% approval rate in the UK – only 17% have a “high connection to sustainable wines”.

Consumers attitudes to sustainability in wine don’t always chime with what the industry might think

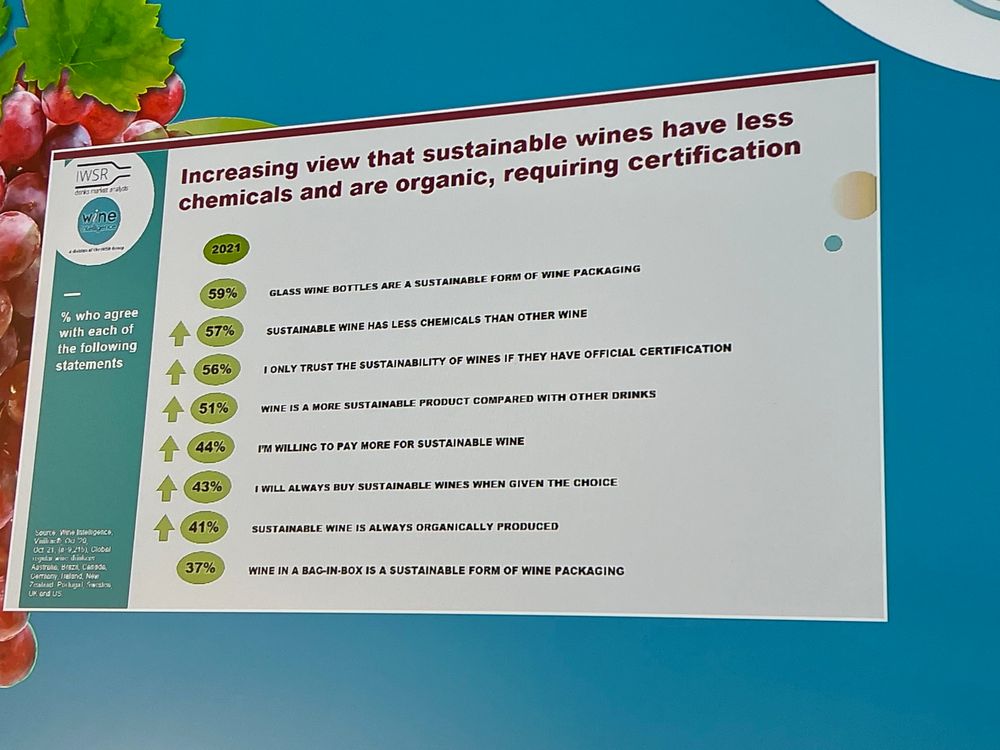

Which is not in step with its research that shows 57% of consumers are actively looking to buy more locally produced food, the 54% who expect brands to support social causes, 47% prepared to give up convenience for sustainability, 44% who will actually pay more for a sustainable product, and 43% who will always buy “sustainable” when possible.

So whist the wine industry is currently getting itself into a lather about the use of heavy glass wine bottles, the consumer does not see them as a problem. Wine Intelligence’s Vinitrac research from October 2021 found 59% of regular wine drinkers agree with the statement that “glass wine bottles are a sustainable form of wine packaging”. The majority (51%) believe “wine is a more sustainable product compared to other drinks”.

As Halstead said: “Mainstream regular consumer wine drinkers do not see glass bottles as an issue for the environment.”

That said 43% says they will always buy a sustainable wine when given the choice, and 44% would pay more for a sustainable wine. But what do they think a sustainable wine looks like and do they know h0w it is made? There is clearly some confusion as 41% of regular wine drinkers believe any sustainable wine has to be organically produced.

Long commitment

What was particularly hard reading for one of Halstead’s panelists, Rob Malin, founder of When in Rome, the alternative wine packaging company that has invested lot of its business in bag-in-box was the the fact that only 37% of regular wine drinkers consider bag-in-box to be a sustainable form of wine packaging.

Uncomfortable to hear, yes, but not anything Malin has not heard before and certainly not reason enough for him to pack up and take his bag-in-boxes home with him. Particularly when he can turn to the new paper bottle format that When in Rome is now pushing and promoting that he claims uses six times less carbon than glass.

Halstead and Malin were joined on the Vinexposium panel, hosted by Lucy Britner, by: James Law, director of brand and development at the East London Liquor Company that claims to have produced the first whisky to be distilled in London and runs its own refill bottling scheme; and Damian Barton Sartorius, co-manager of Barton Family Wines in Bordeaux, that is working on ‘225’ a new wine refill zero waste brand in partnership with Sustainable Wine Solutions in the UK.

Together they were able to push the sustainability debate forward by looking at the real, practical steps being taken by businesses to change the dial on packaging in particular and consumer perception as a result.

Every gram of weight in wine packing can make a difference to its carbon impact, said Barton. Yes, it is going to take a long time to change consumers’ behaviour but that is what the wine industry needs to be investing its time and energy.

He admitted the response to the “refill” aspect of his new 225 brand had been less than he hoped, with around 20% of people returning the bottle to be refilled, rather than the 80% he had hoped for.

“It is the responsibility of the industry to lead by example. It is important to educate the consumer to understand sustainability and to help them get more involved with recycling,” he said.

Each bottle for his 225 brand can be reused up to 30 times before it must eventually be recycled, reducing the carbon footprint of each bottle by up to 95%.

East London Liquor Company is looking to be pioneers in English whisky but also in packaging and refill schemes

Also pushing consumers toward refilling bottles is James Law at East London Liquor Company. When it launched its own whisky brand, which claims to use 60% less CO2 in production and weigh 48% less than its previous bottle, it also introduced the Project Refill scheme to go alongside it.

It simply invites its customers to come to the distillery with any 70cl spirits bottle, be it their favourite gin or vodka brand, and it will refill it with some good East London Liquour Company whisky, plonking its own label, and a duty stamp, on top.

“There is now a generation of consumers that are ready to behave and act in a different way,” said Law. “That appeals to me and how I want to shop in the future.”

Its ambition is to “tweak the undercarriage of the industry to act” and respond to what consumers are calling out for.

“This is a chance for consumers to reuse the millions of bottles that people have in a new way.”

Barton agreed: “If we can get people to switch from heavy to light bottles then we will be doing something positive. But we know it is going to be a very slow process.”

He admitted it would be an even bigger challenge for fine wine producers – he himself comes from the family behind Château Léoville Barton in Bordeaux – but that is the ambition we have to have.

Halstead said the issue the sector has at the moment is not only does the average wine consumer not see glass and heavy bottles as a problem they actually don’t like to pick up a lighter bottle.

“If you give them a lighter bottle they think there is less wine in it and they are not getting as much wine as there is in a heavy bottle,” she said.

Quite how you get around that issue is perhaps worthy of a Symposium in itself.

The Made in Rome range of alternative packaging

Malin at When in Rome was quick to stress his business was not out to “trash the wine industry for using glass bottles”.

But he strongly believes there is a fast emerging market amongst consumers who are looking for practical alternatives to lugging large bottles around, be it drinking wine from a can on a train, for a picnic, or at a concert, or festival.

He is not alone. Glastonbury banned the use of all glass on its vast site, forcing festival goers to “think alternative” when it came to having a drink.

Malin, though, knows it is a tough battle to change people’s habits: “The perception gap is enormous. It is going to be a very slow process, but it is starting to shift.”

Big business must do more

Law said it was essential businesses like the East London Liquor Company are taking the lead on this issue, regardless of consumer demand or knowledge.

He slammed the major multinational drinks companies for simply not doing enough to introduce better, more sustainable packaging and helping to drive and change consumer behaviour towards the brands they want to buy and pick up off the shelf.

“We have to encourage the big boys to behave in a different way,” he said.

He said the major drinks companies were quite happy to “generate” billions of pounds in profit, but not do enough to re-invest some of that money into “the future of the planet”.

Only by getting them to change their behaviour and attitude towards packaging would we really see a sizeable shift in consumer behaviour.

“We are doing the work that is crucial in changing things,” he added, whilst accusing “the big boys” of “green washing”.

Ultimately it will the consumer that decides. “They will lead the shopping experience and behaviour. The demand will come from the consumer to change the solutions down the supply chain they are being offered.”

He added: “We need to lead the consumer by the hand and beat them over the the head about this.”

“Educating the consumer is slow and expensive. It just takes time,” said Malin.

Retailer support

Rob Malin says it might be a slow process in changing consumer attitudes towards wine packaging but it has to be done for the good of the sector and the planet

It is also about finding solutions that major retailers are going to buy into and support. He said when he first started Made in Rome the initial thought was to go down the refill route, but soon realised major retailers were looking for sustainable single use packaging solutions. Hence why it switched to first bag-in-box and now its pioneering paper bottle, that uses a bag-in-box style plastic seal to keep the wine fresh.

“That is what supermarkets want. It is against what we set out to do, but it is part of the process and education story.”

Halstead said there were big lessons for the wine industry to learn from what is happening in the luxury and travel sectors. Luxury and premium tourism is now about being seen to be sustainable and not “showing off,” she said.

She also pointed to research in the US that shows sales of premium 2.25 litre bag-in-box at higher price points are on the rise. “The more engaged consumer is looking at this now. The key is it to talk to the consumer. Not lecture them. To explain the benefits, the fact it is easy to carry, to transport. Start with the personal benefits and then back it up with the broader benefits.”

The panel was agreed that even in 10 years time the vast majority of wine is still going to be sold in glass bottles. But that is not the reason to keep chipping away and making the case for alternative solutions and ensuring whatever bottles are being used are as sustainable as possible.

Halstead said a lot will rest on how quickly the major supermarkets turn to new formats. As they showed with screw caps, they are the ones that can truly transform consumer attitudes and behaviour.

Malin said you only need to look at what is happening in other consumer good sectors. “Every category does it better than wine,” he said, and that should be a challenge in itself for the industry to put right.

- You can read Richard Siddle’s analysis of the e-commerce and online wine debate at Vinexposium Symposium here.

- You can find out more about Vinexposium Act for Change Symposium here.