For this in-depth read Rasmussen visited Weingut Rudolf Fürst, Schnaitmann, Karl H. Johner, Villa Wolf, Jean Stodden and Louis Guntrum.

July saw me embark upon somewhat of a pilgrimage across Germany to discover the unique terroirs of the wineries represented by Awin Barratt Siegel Wine Agencies, one of the pioneering agencies in importing German wines. Along the way, I uncovered the beliefs and thoughts held by the winemakers to coax their terroirs into the glass, their shared goal.

This delve into terroir took me from Franken, to Württemberg, to the Baden, to the Pfalz, to the Mosel, to the Ahr, to the Rheingau, the Nahe and the Rheinhessen.

The winemakers are fiercely dedicated to creating terroir-expressive Pinot Noir/ Spätburgunder. Whether they decide to label their wines as Pinot or Spätburgunder is a personal choice, and depends on the estate. Some choose Pinot Noir for marketing and sales purposes, whereas others defend Spätburgunder. Some choose Pinot Noir when there is a focus on French clones. This quality has seen them slowly but surely start to sit in their own category on so many world-renowned restaurant lists; The Ledbury lists multiple examples as does Texture and Trishna.

The interesting question to ask is: what is the identity of German Pinot Noir? It’s a difficult question to answer as there is such variation with regards to winemaking and clonal selection. I think there are fascinating results to be had with old German clonal material when handled in a less interventionist manner; there is this mysterious, slightly more forest-like, punchy side to the wines that I find deeply intriguing.

Comparative density plantings at Fürst

Franken and Weingut Rudolf Fürst

Franken is the most easterly of the wine regions based around the Rhine and its tributaries, the region is composed mainly of three different soil types: limestone, gypsum and iron rich sandstone. The latter, in particular, produces really exciting Riesling and Pinot Noir. Franken is one of the cooler regions which is no bad thing – warm years are easier to handle and low rainfall is manageable.

While the soils here are exciting, the clones aren’t always the best. Sebastian Fürst, winemaker at Weingut Rudolf Fürst explains: “there’s a lot of Pinot Noir here, but there are also a lot of easy, lower quality clones with high yields. Clones are so important when it comes to quality. We like old genetics in our plant material.” This is why Fürst’s grandfather removed these lower quality clones, leaving the high quality German clones, and replanted with French clones; the most recent plantings in 2004 were French selection massal vines, which Fürst believes brings more finesse to the wine.

Fürst, who this year was named German Winemaker of 2018 by Fallstaff Wein Guide, is also trying to figure out which density of vines produces the highest quality. The somewhat legendary Hündsruck vineyard is planted at a density of 8,000 vines/ha. However, there is an experimental baby plot planted at 18,000 vines/ha, something that Fürst initiated after having been inspired by friend Hubert Lamy’s experiments (Lamy has planted at 12,000, 18,000 and even 30,000 vines/ha).

German Winemaker of the Year, Sebastian Fürst

Vineyard work is carried out organically, “to work in a natural way is simply what we like to do,” apart from the use of phosphorus acid instead of copper – in order to use less copper. Although this is not yet included within organic regulations this is something that Fürst believes ought to be and hopes this will change. The family has always believed in the effect of good compost which it has been making for 40 years, and applies every couple of years. “Good composts = alive vineyards,” he mused.

In the cellar, the moon and weather is respected. When there is a low atmospheric pressure (for example with a storm), or when there is a full moon, wine is left alone and not touched.

Regarding stems, this varies vintage to vintage, with hot years seeing approximately 35-45% whole bunch. This is something that might alter a little; in the cellar we tried Hündsruck via two barrels; one with 60% whole bunch and the other with 100%. The results were astonishingly different; the 60% being pretty, pure and perhaps more elegant but the whole bunch portraying lively pink peppercorn, basil, spearmint and real zing, that I think will develop into something beautiful with age. Fürst’s eyes gleamed when we were discussing this, and we pondered on whether this could be an experimental bottling in the future.

Grapes are sorted in the vineyard, and a period of cool maceration occurs, followed by indigenous fermentation. The cap is kept wet, with very gentle remontage, and punchdowns performed late in the process. Fermentation lasts between seven to ten days and a short maceration occurs after the fermentation to cool the wine down and keep aroma. The wines are then basket pressed into 228L barrels.

Speaking of sulphur, Fürst explains that it is important to add a very small amount of sulphur onto the grapes in order to let the strong indigenous yeasts take over the fermentation as opposed to the ‘dodgy’, weaker yeasts. He muses: “we put so much effort into our vineyards. Everything is done by hand and this is where the wine is made. We use little amounts of S02 in our vinification – removing this is a funny notion. Using low levels of sulphur is a useful tool to create precise and expressive Spätburgunder.”

All Pinot Noirs are bottled under cork due to some levels of CO2 in the wines, which needs cork in order to dissipate gradually.

When tasting the wines, the difference between the three vineyards is astounding. The Tradition Spätburgunder 2016, their entry-level wine, speaks of earthy, woody tones, pine cones and forests at night. It is composed of 90% German clones. Meanwhile, the Klingenberger Village 2016 (French clones) gives classic bright red fruits, violets and sour cherries.

Whether or not this is down to the clone or down to the place remains something of a mystery, with Fürst emphasising, “sometimes the place is more important than the clone.” Perhaps sometimes the two work in tandem?

The three Grosses Gewächs wines that Fürst produces – Centgraftenberg, Schlossberg and Hündsruck – all have vividly differing personalities.

Centgraftenberg, planted to almost 100% Dijon clones, is very young and somewhat playful; at this stage in its life it gives a little but it is very young; it is still very much hiding in its shell. It has a beautifully elegant, poised and cool presence with spearmint and black fruit skin and it’s clear this will develop into a wine of true elegance in that unique Pinot way.

Schlossberg and Hündsruck are planted to 50/50 German/French clones (Freiburger and Ritter clones and Burgundy selections as well as Dijon clones). The Schlossberg really draws you in, already more open in profile. It’s somewhat a racehorse of a wine, with a sleek coat but that dense, very real underlying power. There is real energy here.

Finally, the Hündsruck has a spicy, blood orange and nutmeg profile with grip and more of a burly muscular side to it, with incredible length and an electric mouthfeel.

In conclusion…

Is this difference in elegance and coolness versus power, density and muscle a question of site or of clones? Perhaps we will never know, but regardless it leaves one pondering. Both sides to this stone are beautiful expressions, and thus Fürst exemplifies the capacity for Pinot, be it German or French clonal material, rooted in German soil.

The Württemberg and Weingut Schnaitmann

Rainer Schnaitmann, a man with hair as energetic as his soul, is not only leading the dialogue for Württemberg but also for organic viticulture in the region. Originally wanting to study architecture, he changed his mind after working in the mess during military service. His father had sold their grapes to the local cooperative, which is still the general practice today for the region (approximately 85% of the grapes are sold to the coop). Rainer took the helm in 1997 and by 2010 had fully converted to organics, which is deeply important to him, as is using indigenous yeasts through all wines. The estate has grown from 3ha to 25ha within that time.

Standing in his vineyard overlooking Stuttgart, Schnaitmann muses: “It’s going to be our earliest year yet. I like to pick grapes with cold fingers, not in short trousers, but it is useful to learn how to handle warm vintages – 2003 taught us that.”

Pinot vineyard at Schnaitmann

Pinot Noir is important to Schnaitmann in this region that is dominated by mass-produced low quality Trollinger because it is an important vehicle for showing what a certain terroir can do. We stand quietly on his oldest vineyard, the Fellbacher Lämmler vineyard – a Grosses Gewächs site planted on limestone and marl – and he reflects on how he has to be particularly careful with Pinot in warm vintages.

“The crucial point for Pinot Noir is the picking date. In 2015, our hot vintage, if we had waited just three days later, alcohol degrees would have gone up by 1% and the pH would have risen from 3.3 to 3.6. That said, you learn so much from tasting the berries alone and relying less on analysis.”

What Schnaitmann is achieving with his Lämmler vineyard is quite spectacular. The 2014 and 2015 next to one another showed a strong, vibrant and alive nature and a certain symbiosis; they are sibling wines and the cool site is evident. The Japanese fruit fly, Drosophila suzukii, famously caused havoc in 2014, but despite it being a tricky vintage, he remembers it fondly.

“It was difficult but good. If the fly likes your grapes, you’ll like them too. It’s time to get picking.”

Meanwhile in 2015, despite the heat the resulting wine is remarkably elegant and with incredibly soft tannins. Both wines have a certain subtle reductive quality, a gentle white smokiness. We tasted a 2012 Spätburgunder from the Bergmandel vineyard, which was simply stunning with its peonies, rose petal and rosewater notes. Through all of Schnaitmann’s wines runs a certain wild plant characteristic, whether it be wildflowers or moss, sometimes with petal-like characteristics – a certain beautiful wildness, but all the while maintaining such poise and quiet confidence.

Baden and Weingut Karl H. Johner

At Weingut Karl H. Johner viticulture is carried out organically without certification, and soils are worked under the vines, which Patrick Johner believes helps the immunisation of the vines and gives the resulting wines more structure.

Veraison at Johner

Standing in the Steinbuck vineyard, we saw something very rare this time of year: veraison. Perhaps hardly veraison, but the very start: one sole miniature red berry in the centre of the vineyard. Patrick also believes this may be the earliest vintage yet. Green harvest is carried out here where necessary (predominantly to aid air circulation), except where bunches are evenly spaced and, in the cases of bunches affected by millerendage, which is hailed as a ‘good thing’ as this adds concentration and improves air flow. Soil here is ancient volcanic with loess from the now inactive volcano the Kaiserstuhl.

There are both German clones and French clones at Johner. Style here is particularly bold and fruit forward. Cooperages are a focus, and they are chosen to preserve cherry and dark berry fruit flavours.

The Steinbuck site, comprised of the French clones 777 and 667, was planted in in 1998. Karl Johner comments, “it starts to get interesting now. There is no technique to compensate for vine age.”

Both the 2013 and 2015 express heady, rich, opulent red fruit. There is 100% new oak here, which further drives the fruit into prominence showing damson plums and black cherries. The 2013 shows pretty elements of ageing with some earth tones and a pretty crushed lilac edge. This is definitely a wine that needs time to come into its own.

The Oberrotweiler Eichberg vineyard, however, was planted in 1980 with German clones. For the 2013, an underlying minerality is joined by mossy, undergrowth tones joined by marked oak. Meanwhile, the 2015 shows a stunning brightness of cherry stones, raspberry pips and dry earth, with minimal oak noticeable.

That said, oak does leave its mark, so the tasting left me pondering old qualitative German clones versus French clones. I was left wondering what could be if Steinbuck and Oberrotweiler Eichberg were vinified in the same manner in a neutral vessel; perhaps concrete…? What would the site and clone convey?

The Pfalz and Weingut Villa Wolf

In the Pfalz with Villa Wolf, the stars lie in the single vineyard Rieslings but the estate also produces fruit-forward, bright Pinot Noir (50/50 old barrel/steel), as well as an easy-to-drink Pinot Noir rosé. The wines are forward, with real true-to-fruit typicity. They make for ideal introductions to what Pinot Noir can do in Germany. A sparkling Pinot Noir produced for the Norwegian market packs a sweet punch at 16g/l residual sugar but shows potential for sparkling German Pinot on the international market.

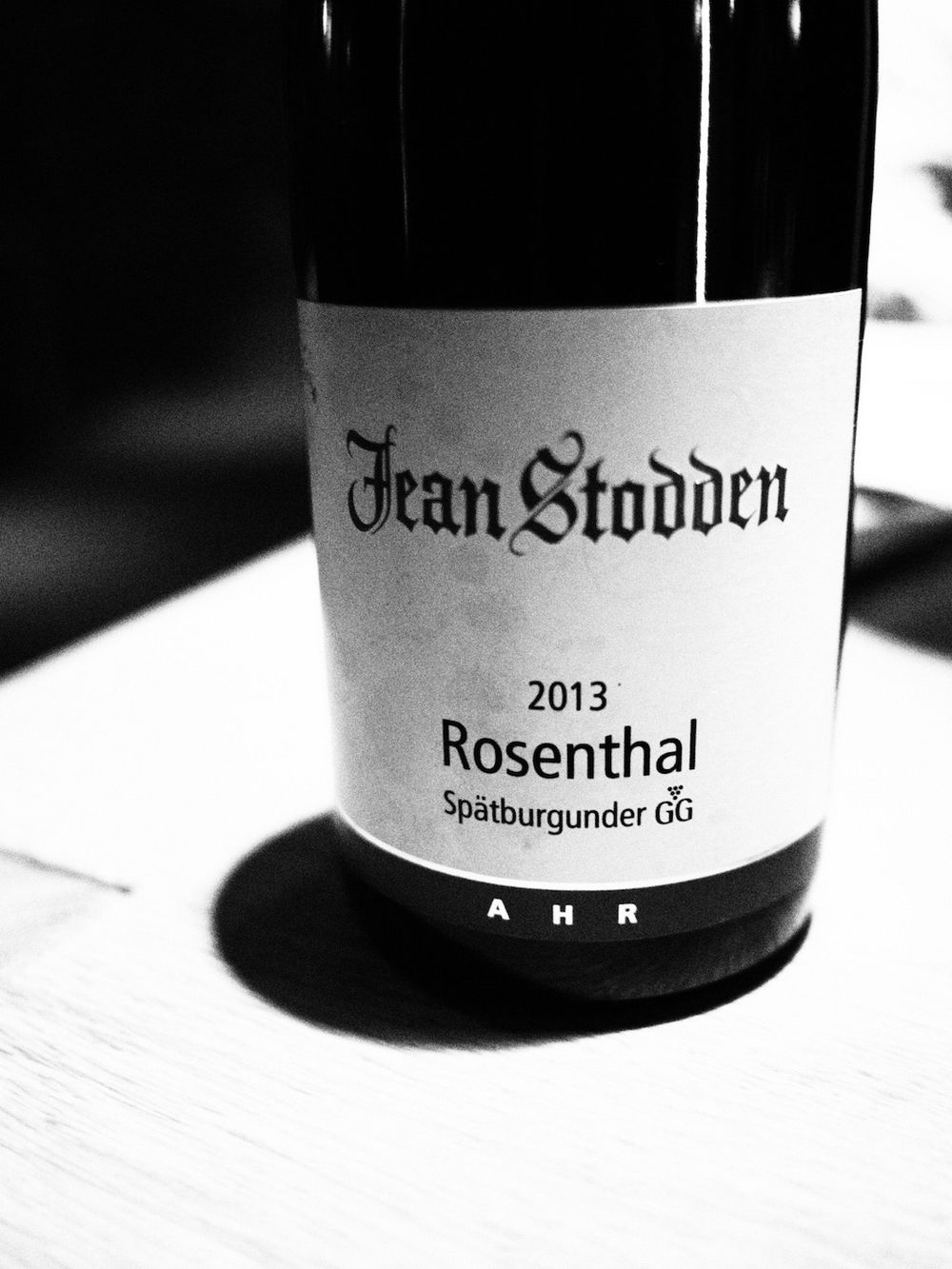

The Ahr and Jean Stodden

Up in the lesser-known Northerly Ahr, we stand up on a ridge overlooking the Ahr Valley in the Herrenberg vineyard with Dr. Brigitta, Alexander Stodden’s mother. Deep forests border us. It’s quite breathtaking on this red slate and greywacke, rocky scenery looking down 60° slopes. However, as is often the case, unfortunately there’s quite a bit of herbicide around here and some desolate looking soils, so it’s a welcome relief to see the Stodden vineyards very much alive, having been worked earlier this year and now humming with wildlife.

This year it’s been “around as hot as Italy,” and Stodden expects harvest to be the earliest ever, clocking in three weeks earlier than last year.

The entry level Spätburgunder 2017 here is really expressive. A combination of ancient German clones and Burgundy clones (when the vineyard is replanted it is planted to both Burgundy clones and a massal selection from their Alte Reben own-rooted vineyard that was planted over 100 years ago, where clonal material is ancient German). They have named this the Stodden Clone. The wine is earthy, woody and very pure – the sort of forest notes that come directly from the grapes as opposed to the barrel, met by black cherry skin. Indigenous yeasts are used together with commercial Spätburgunder yeasts in order to ensure that the wines finish dry. Acid is bright and perfectly balanced.

Dr. Brigitta comments: “wines must have two feet to stand on: acid and tannin, and we know nothing is more beautiful than drinking old Pinot Noir.”

At Stodden it is the Grosses Gewächs wines that really sing. The new François Frères barrels are perfectly integrated into the wines, simply giving a gentle spicy backbone and lending structure. It is the perfect example of the rare mastery of oak whereby no overt oak character is transferred.

These are small classified sites with really exciting terroir. The Sonnenberg sits on greywacke and grey slate, planted to the Mariafelder clone, the Rosenthal sits on greywacke, loam and loess, planted with cuttings from Alte Reben (old vines), and the aforementioned Herrenberg sits on coloured slate and greywacke, planted to French and old German clones.

Vineyard at Stodden: the harvest has come three weeks early

We tasted the 2016s (wines spend two Christmases in barrel). The Sonnenberg had a dense, smoky nose. The acidity is tense and so poised, with the wine developing to display irises and cherries – so very Pinot, and so pure. Redcurrants and spice develop with crunchy yet closed minerality at this stage with a real mouth-coating stoniness.

Finally, the Rosenthal somewhat diverted my palate’s mind. It snuck up and stole my tastebuds just for a moment. The 2016 was ever so delicate, lifted, pretty and floral; an elegant ballerina nose. Wild flowers and peonies meet dry heathland. The 2013 showed us what this vineyard can do: dusty roses and dusty irises shimmer around the glass, and the wine has the effect of seeming to want to put me in another headspace, an almost trancelike state of being. It is ever so clear that this wine will age for a very long time.

Finally, the Herrenberg GG 2016 is more of a punchy, “hello, here I am, this is German Pinot!” kind of wine. It jumps out of the glass and grabs you to show you its red cherry palate and stony, broad, densely iron-clad mineral palate. There is a potent energy in this wine, and the vibrant tannins bring its acidity to the forefront. Such length.

The Rheinhessen and Weingut Louis Guntrum

Louis Guntrum is situated on the Rhein-Terrasse of the much larger Rheinhessen region. Louis Guntrum’s first foreign customer was ABS and, due to being hesitant about the success of Spätburgunder-labelled wine, Guntrum labelled his export wines ‘Pinot Noir’ and, following the ensuing success, now labels for all of his markets as such. This is a not an isolated case.

Guntrum’s Pinot Noir 2016 is a really impressive gateway wine into the world of German Pinot Noir. It is aged in large German oak barrels (called shtucks) for 15 months. What struck me the most here was how pure and silky the tannins are, it is a soft, gentle, enticing Pinot that is so ready to drink and moreish – the perfect Pinot Noir for consuming straight away.

Guntrum has recently commenced a Pinot Noir Reserve (in its second vintage), which is aged in small Alliers oak barrels. There is a lot of black fruit; smoky clove spice and some ripeness here. This will be interesting to come back to with time.

And so..?

Spätburgunder appears in many guises and it’s exciting to see its increased presence in the UK. It is interesting to see qualitative ancient German clones and we see some very exciting results with this, such as in Stodden’s Alte Reben vineyard and GG vineyards planted to the old clonal material.

With the example of Stodden, it is clear that with high clonal quality and exceptional terroir, oak can be integrated with great subtlety. It is crucial to ensure that this is the case as I fear a lot of German Pinot still suffers from too much oak and extraction. I think the essence of Pinot Noir lies in delicacy, and whereas perhaps Spätburgunder has a different type of delicacy to that of French Pinot Noir, there is a forest like delicacy, which, if treated correctly, can result in ethereal qualities too.

I would still love to see Pinot Noir, Spätburgunder and Frühburgunder all fermented in inert vessels and treated in the same way, from the same producer and from similar sites, in order to gain real insight into clonal capacities… Perhaps one day someone will experiment? (please?)