Not only did the Curly Flat Pinot Noir Technical Tasting Seminar give the Masters of Wine a rare insight into Pinot as a varietal, it also posited that the concept of terroir is possibly a deeply engrained socio-religious construct.

The moment I read about this tasting of Curly Flat Pinot Noirs I knew I had to go: it so totally pressed my geek buttons with its promise of “the rare opportunity to taste, in isolation, how different Pinot Noir clones and different winemaking methods affect the taste sensation.”

Matt Harrop, Jennifer Kolkka, Miles Cornish MW and John Atkinson MW (l-r)

The ‘technical tasting seminar’ was held on Monday, 16 October at the Institute of Masters of Wine. Miles Corish MW, owner of Milestone Wines, representing the estate in the UK, presented the master class together with Jenifer Kolkka, co-owner and founder of Curly Flat, and winemaker Matt Harrop, aided and abetted by John Atkinson MW who provided tangential but thought-provoking insights throughout.

While we indeed got our fair share of geekdom, the sheer deliciousness of the wines, along with Jenifer’s acknowledgement of a dream fulfilled in this estate, the evening did not seem like a dry technical seminar but a joyous, communal delight in this multi-faceted variety.

“Curly Flat have been bottling individual components of different clones, yeast strains, vineyard blocks and so on,” explains Corish by way of introduction. The technical booklet notes the “detailed trials which involved hand-bottling small batches of different components from each vintage in order to continually gain better understanding of how to make the best possible expression of site and cultivar.”

Corish notes that being able to taste such components is a luxury usually reserved for winemakers just before blending and bottling. But we tonight are in for a treat.

So where is Curly Flat I hear you ask?

Jenifer Kolkka

Kolkka then took over to outline the history of this relatively young estate: Curly Flat was founded by her and her husband Phillip Moraghan in 1989. He found this site in the Macedon Ranges, one of the coolest sub-regions of Victoria, Australia, looking for the perfect spot to grow Pinot Noir – altitude and distance to the ocean make it so.

Laying the foundations to the winery, 2002

They planted between 1992 and 2000 and now have 33 acres in total: three quarters of that is Pinot Noir, the rest is Chardonnay and Pinot Gris.

By 2004 all of their blocks were in full production while 2017 marked their 20th vintage. Kolkka emphasises the uncompromising quality focus of the estate: “Phil and I were both bankers, we had no children, so Curly Flat is our baby. Because we had no external investors there was nobody asking for dividends, so we put every dollar into producing the best wine we possibly could.”

But far from being hands-off investors they were very hands-on from the beginning. Kolkka stresses the importance of her very dedicated and long-standing vineyard crew, tending the vines that root in the deep basalt soils of the site. “We loosely follow biodynamic principles but we’re not zealots,” Kolkka says, they will resort to synthetic treatments when the disease pressure gets too much – but only in difficult years. “In a warm year we manage to get along on just copper and sulphur,” adds winemaker Matt Harrop before plunging us straight into the first tasting flight.

Flight #1: Comparing different clones

This first comparison is about different clones. The estate has a total of five Pinot Noir clones: 114, 115, MV6 –the famous Mothervine 6 that is said to have reached Australia in the 1830s from Burgundy– as well as Mariafeld and D5V12.

Harrop says: “MV6 is the closest thing we have to an indigenous Pinot Noir clone in Australia.”

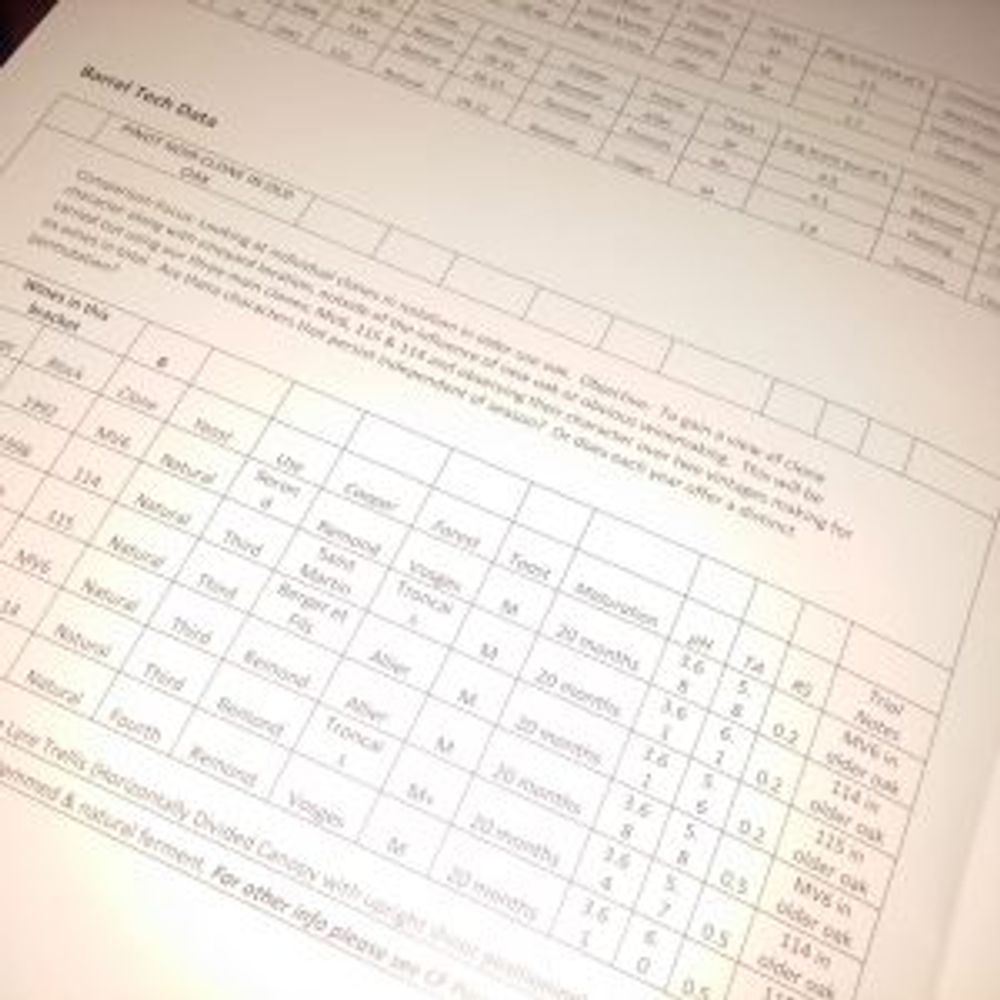

In order to make the samples as comparable as possible we taste the same (and similar) blocks of three clones in two different years, vinified in the same manner, all raised in used oak. What we compare is 114, 115 and MV6 from the “warm and dry” 2013 vintage and the same clones from the “slightly cooler and more even” 2010 vintage. Indeed there are communalities within the samples – I come away with this impression:

MV6 – savoury and herbal with real tension – Matt Harrop says: “More robust, tannic, more black-fruited and a touch of spice.”

114 – flirtatious and aromatic, some grip – Matt Harrop says: “Very red-fruited, a lovely blending clone, goes really well with MV6.”

115 – plump fruity, lovely acid – Matt Harrop says: “Robust flavours, but very sensitive to the sun, an early-ripening clone.” – which in turn explains that plump fruit.

But, quite apart from that, these clonal samples are delicious – all in their own right and many with striking length. We now all know that we’re onto something very good. At this point, Atkinson adds a few thoughts on the Holy Grail that is Burgundy and how much this influences the way we think about Pinot Noir – and come to think of it – how most of us are also still taught about Burgundy.

Atkinson asks us to imagine medieval France; the size of the churches in these Burgundian villages is still impressive. But he asks us to picture a much lower population and a preoccupation with the Christian faith, he reminds us that the vineyards were originally planted and tended by Cistercian monks. “What you have is God’s creation. Everything is set up in this world view where we [humans] are good observers but poor creators.”

According to Atkinson, this view is prevalent to this very day – whether you see what happens in the vineyard as an act of god or of nature. He believes that this culturally deep-seated assumption still informs the way French vignerons talk about ‘terroir’ today, even those who have adjoining vineyards and make fundamentally different styles of wine still individually explain themselves via ‘terroir’.

Uniform bud burst at Curly Flat

It is the wishful thinking (or the fervent belief) that what we taste in the glass is really nature’s grace and not the work of humans. Seen like this, as a deeply engrained socio-religious construct, talk of God-given ‘terroir’ that so often is utterly infuriating to the scientifically minded, becomes explicable, even understandable. But of course it also calls these convictions into question. Atkinson also notes how this view “discriminates” against Burgundians with lesser vineyards, “on the wrong side of the RN74” – the famous Route Nationale along the vineyards of the Côte de Nuits, now re-named D974.

Over the evening, Atkinson, his head clearly buzzing with too many ideas to cram into one tasting, also draws our attention to classification of vines into isohydric and anisohydric, which is how they react to water stress; to the importance of winter dormancy; he even muses on various pruning regimes and their effect on the ability of the vine to channel its growth.

Tasting #2: New versus old oak

The next tasting, by contrast, is much more straightforward: it is all about new versus used oak: we get the same block of MV6 raised in new and neutral oak from the 2012 and the 2013 vintages – in both vintages the wine can take the new oak very well but shows more charm in the neutral oak. Many tasters find the textural difference to be the most important. For me the robust beauty of MV6 is what is most striking across these four samples. That 2012 is a great vintage is also clear, so clear that I swallow my samples.

Geeks’ delight: all the technical detail you crave at the London seminar

The technical data provided is comprehensive.

Tastings #3 and #4: stems and yeasts

Two further comparisons follow – between two vintages of de-stemmed and whole-bunch ferments of clones 114 and 115 blended; then between spontaneous and inoculated ferments from the 2017 vintage. The differences are evident, and questions fly across the room, both technical and philosophical.

However, what is striking to me is that despite 100% whole-bunch, which some see as extreme, or the frowned-upon use of inoculated ferments, the wines themselves shine through all of it. Perhaps it is for this reason that I am unlikely to argue for pluralism in these approaches – I am content to sniff and sip, to muse on the chameleon nature of Pinot Noir and its ability to shine in so many different incarnations.

The crowning glory comes as we get to taste the “finished” wines, ie. the estate’s wines as they were bottled – from all of the clones on the estate and regardless of the separate component bottles that we were so fortunate to taste. We get 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014. All four are lovely, but 2012 is a stunner – lovely now but sure to evolve.

Harrop notes how instructive and revealing the bottling of these components is: “It is fascinating to see not only the difference in each vintage but the differences reproduced in the next vintage and the effect these components have on Pinot Noir.” “We do this at Curly Flat year in year out – that was the whole idea of taking these library wines all those years ago,” says Kolkka. “We’ve been gathering up these library wines since 2004 and this is so exciting for me,” she says, smiling. “This is the first real tasting we have made with these wines and I’ve been waiting for years.” It was our great pleasure to share it with her.