As well as having some of the world’s most prestigious wine regions and producers, Italy also has a vast array of local indigenous varieties that are very much the DNA, and building blocks with which many of its premium wines are made. A diversity that is of constant interest to wine buyers and importers as our debate with leading Piedmont producer, Scarpa, showed. (All photography by Thomas Skovsende).

Our thanks go to Scarpa wines for helping to organise our Italian indigenous varieties debate, Vinoteca in the City for hosting us, and our panel of leading UK wine buyers and importers including:

The Scarpa debate was an opportunity for leading importers to hear directly from one of Piedmont’s leading producers about the long term commitment it has to working with and promoting the region’s indigenous varieties

- Nik Darlington, co-founder, Graft Wine.

- Roberto Cremonese, premium account manager, Bibendum.

- Michael Palij MW, managing director, Winetraders.

- Lucie Parker, sales director, Jeroboams.

- Rebecca Palmer, associate director and head of wine buying, Corney & Barrow.

- Andrea Briccarello, business development manager, Jascots Wine Merchants.

- Giovanna Cariola, general manager, Vinoteca Farringdon

- Sergio De Luca, director of buying for Italy, Enotria&Coe.

- Andrew Johnson, managing director, Woodwinters.

- Davide Champion, chief executive, Scarpa.

- Silvio Trinchero, winemaker, Scarpa.

When it comes to choosing a premium wine on a wine list it’s fair to say the country, region, or name of producer might come higher up the pecking order than the grape variety it is made from. Particularly if it is not one of the Big Six varieties (Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Pinot Noir) that dominate winemaking all over the world.

But when you are looking for a wine that stands out from the norm and is a true reflection of the wines a particular region or sub-region can make, then that is when working with so-called local grape varieties can really make a difference – particularly for sommeliers looking for a story, as well as a wine to sell.

It is also what, increasingly, more discerning wine buyers and sommeliers are looking to list, particularly if you want wines with a true sense of place in your range.

It was interesting to see the level of interest there was for busy buyers and importers to take part in this debate. When asked if they would like to find out more and discuss their thoughts on Italian indigenous grape varieties, and the wines of Scarpa and Piemonte in particular, the majority of buyers we approached to take part jumped at the chance.

Indigenous – and Italy

Enotria&Coe’s Serfio de Luca says he has been a strong supporter of Italian indigenous varieties for over 40 years and is pleased to see so much opportunity and focus being given to them now

Sergio de Luca said he was particularly pleased to see the attention being given to indigenous varieties in this way as it is something he “has pushed for the last 40 years” during his long and esteemed career as the face of Italian wine at Enotria&Coe.

Nik Darlington said he was very keen to take part as the whole notion of indigenous varieties is what got him into wine in the first place through his first business, Red Squirrel Wines. A wine importing and retail business founded on the premise of searching the world for wines made from local varieties each with their own sense of place and a story to tell.

“The whole point of Red Squirrel was indigenous varieties,” he added. It is why he teamed up with David Knott of The Knotted Vine to create a joint business, Graft Wine Company, as they both shared the same philosophy to go out and “try find the most authentic wines we can”.

It’s also why Italy makes up such a significant part of its range as each region has so many indigenous varieties to explore and enjoy, he said.

Michael Palij MW said he has had the chance to “introduce tens of indigenous varieties from Italy” through Winetraders and for him they are the gift that keep on giving. Italy as a whole makes up 75% of what it sells.

“That’s the way forward, that’s also personally where my interest has been for the last 30 years. I am not interested in what a Chardonnay tastes like from Italy. That’s not to say Tuscany can’t make, for example, nice Cabernet.”

Michael Palij MW says Italy is blessed with so many indigenous varieties the challenges is more about which ones do you really focus on

There is, though, a challenge, he added. There are simply so many local varieties in every region in Italy that it can be a challenge to “communicate” about them all “down the food chain” and through sales teams all the way through to the end restaurant or wine merchant and their customer.

“Many importers tire, and I do too, of facing that challenge,” he admitted.

But is also a challenge he is more than willing to take on and Italy still makes up about 75% of what Winetraders does.

Rebecca Palmer says Corney & Barrow is putting a lot more focus on Italy as part of its wider strategy to diversify from its strong traditional base in France.

“Italy has been rising in importance in recent years and we actively continue to scout for producers at all levels,” she added.

When it comes to indigenous varieties it is very much “part of the parcel” of what Italy offers. “It’s part of Italy’s viticultural disco ball,” as she so succinctly puts it.

For her indigenous is “about a sense of place and authenticity” and Italy is the place to go and find those wines.

How important the variety, however, is in the final buying decision will depend on a number of factors, she added. In some cases it might be the name of the producer that is more important and what gets the deal done – particularly when it comes to the most coveted fine wine producers.

Rebecca Palmer says when she looks to buy an indigenous grape variety she wants to find out that is a real “benchmark” for what that grape variety can do in that wine region

“Then it is not about the grape variety, it is very much about that producer.”

But equally it will also go out specifically to source a Nero d’Avola, or Negroamaro, or a Falanghina “at X, Y, Z level”. “It’s very much about what we feel the market, or our customers, want and finding wines that we feel are benchmarks from that particular variety.”

Crucial difference

Andrea Briccarello says as an ex sommelier “native grape varieties were crucial,” particularly at the top end of wine lists, and remain very relevant in his business development role at Jascots working with restaurants and top hotels.

“I think there is still room for improvement in finding and sourcing and selling local varieties,” he added, particularly in offering them by the glass and on tasting menus. But there is a “lot of opportunities” for these varieties in venues that have big lists and selections.

Lucie Parker said she was very happy to take part in the debate as Italy is one of Jeroboams “specialisms” and works well across its business.

Italy and its indigenous varieties is very much a speciality for Jeroboams, claims Lucie Parker

“When it comes to Italy and indigenous varieties we are trying to cover a lot of bases,” she said be it fine wine for private clients, entry level for the trade and “something in the middle” for its shops.

She said that whilst there will always be demand for “Barolos and Brunellos” it is also good to be able to offer those customers something new and different which is where indigenous varieties really have a role to play – particularly with the size of the Italian on-trade in the UK. “To have other things to offer is a real point of difference,” she added.

“So today it’s interesting to hear about things like Terrazzo, whereas everyone has got a Barolo and the mainstream stuff. It’s never going to be top selling for us, but it has got a place if it can offer that point of difference for the customer.”

Horses for courses

Andrew Johnson said Italy makes up around 40% of Woodwinters’ range and is the “biggest and best thing we do”.

When it comes to looking at local varieties, Johnson said you can separate them out between “indigenous” and very well-known varieties such as Nebbiolo and “indigenous” and a variety like Grignolino in Piedmont which is a lot more specialist.

So it is understandable that producers will be swayed to use better or lesser known varieties depending on how well known and sought after wines from their region are. It is much harder to go down the indigenous route in what he sees as a “satellite” region versus somewhere as prominent as Piedmont.

Andrew Johnson says it can be quite a difficult balance for producers to focus on indigenous varieties vs more commercial grape varieties

He was also quite to point out that just because something is indigenous, it does not automatically mean it is any good. It’s the same with terroir. You can also have very bad terroir, he said.

“You have to look at each individual circumstance,” he added. “I think it is a shame when you have got grape varieties that thrive in an area to then grub them up and put Syrah or Cabernet or Chardonnay in there. But there is also a different side to the story. Maybe a winemaker wants to try their hand at trying to create a great Chardonnay, Cabernet or Syrah and if that plot of land does lend itself to that variety then why not do that.”

No-one is complaining, for example, about Sassicaia being made from Cabernet in Bolgheri, he added.

Parker agreed: “You have to take into account market forces. There’s a reason why growers are putting Glera into the Prosecco region as they get paid for that, but it is also what consumers want. That’s what the demand is at the moment. We don’t want indigenous varieties to disappear, but equally you have to supply the market with what it wants. Tastes also change. People are looking for that freshness and vibrancy, but that might change again in 10 years. You can’t push people into something they don’t really want.”

But when it comes to sommeliers most are looking for indigenous varieties, stressed Johnson and that’s where the real opportunity lies for them. “My clients, on the whole, are looking for indigenous varieties from classic regions.”

As an importer, however, he agreed with Parker, that you need to make sure you have wines and varieties that can work at all the main price points.

Bibendum’s Roberto Cremonese says style is now key for deciding which wines to list so the challenge and opportunity is there for producers to work with indigenous varieties that can make wines with the styles that buyers and consumers want to drink

As Italian specialist at Bibendum, Roberto Cremonese argued he was more focused on the style of wine a producer was making rather than the grape varieties per se. When he first started in wine it was very much about the big powerful Super Tuscan wines and the high 90+ points they were getting. Now the balance has switched to what he sees as more elegant, everyday drinking wines that are lower in alcohol. If the grape varieties being used can make those style of wines, then that is what is most important to him. “Before it was all about extraction and fruit. I really like the current style.”

Reputation counts

Darlington said it has had good success in selling a wide range of lesser-known Italian varieties – from Freisa to Dolcetto and many others – and where it works best is where the “producer has already established a really good reputation for one of the top wines”. Be it a Barolo, a Barberesco, or a prestigious variety or appellation.

“If a producer can establish a really good benchmark for that, then people will gravitate towards them.”

It helps put their flag in the ground and allows customers to feel comfortable going to them and then pick up other wines and try different varieties as a result.

“If you can establish that reputation then people will come flocking for the more unusual and niche varieties,” he added.

Nik Darlington says a producer with a strong reputation in a particular wine region can really help to push indigenous varieties as buyers are drawn to the producer’s name

Italy also has an advantage even with its most well-known indigenous varieties, like Nebbiolo, as they “still quite exotic and unusual” compared to Cabernet Sauvignon which is grown everywhere, claims Darlington. But whilst you can get cheap Cabernet from all over the world you can’t get cheap Nebbiolo and, outside Italy, it is only being grown in a few places, he added.

“There is something to build on there. There is a mystique and exoticism to these high-end varietals.”

Then, of course, he said there is also pronounceability and how easy it is for consumers to actually say the name of the grape variety and remember it.

On-trade view

Giovanna Cariola said she had definitely “seen a shift” in attitudes and interest towards indigenous varieties over the last five years woking in different roles across the UK on-trade and now as general manager at Vinoteca in Farringdon. So the consumer interest is definitely there.

Giovanna Cariola says there is definitely consumer demand at Vinoteca for Italian indigenous grape varieties

When it comes to the list at Vinoteca then Tuscany is probably leading the way, she said, with more wines coming through from southern Italy. But like many of the importers on the panel, it too is looking to support and source small producers that can tell a different story – like a Primavera Lambrusco.

The challenge in the on-trade now is having the staff with the time and knowledge to be able to sell and really get behind indigenous varieties – particularly niche and unknown grapes, said Enotria’s Sergio De Luca. The sector is a very different place, post Brexit, to what it was a few years ago when it is much easier to promote little known varieties.

Palmer said another issue for importers looking to place these kinds of wine into the on-trade is there was much more “openness” to try and list these kinds of wines before Brexit, Covid and the cost of living crisis.

Many of the younger, more ambitious sommeliers, particularly from Eastern Europe, have gone out of the trade and “those on the ground don’t have the time to do the hands sell – and that is a real shame,” she said. “The number of bins on lists is also going down. I hope it will rebound.”

Those that are, added De Luca, are also now being pulled into other areas of the business and can’t fully concentrate on wine.

Regional support

The buyers said they would like to see more regional and local support to help producers promote and put their weight behind indigenous varieties

Whilst there is clearly a lot of support and interest in indigenous varieties amongst the buyers and importers, they are also not wines that jump immediately off lists and need all the help and support they can get. Both Cariola at Vinoteca and Enotria’s Sergio De Luca felt more could be done by some of the region’s wine bodies and local consorzios to help producers in those regions promote what they are doing and ensure there is a future for these local indigenous varieties.

“I would expect to see a bit more marketing and a bit more help from the consorzios to do this,” said De Luca. “We need more co-operation between growers and associations to make it easier.”

He cited the example of trying to introduce a number of years ago Pelaverga from Piedmont, which he describes as “a beautiful grape variety” but struggled to get into the market as there was so little knowledge about it then. So, whilst there is now a lot more interest and knowledge in the market from customers to “accept these kind of grape varieties” it still needs the regional support to make the breakthrough.

Focus on Scarpa

Davide Champion, chief executive of Scarpa, was able to explain just how committed the producer is to indigenous varieties and how it sees it as its historical duty to support and make wines from its local varieties

The buyers then had the opportunity to hear first hand how a leading, historical producer – Scarpa – is firmly committed to working with indigenous varieties in such a classic region as Piedmont – as well as taste through its range of wines.

Davide Champion, chief executive of Scarpa, said it was particularly helpful to hear the buyers’ views on where indigenous varieties sit in the UK premium wine market.

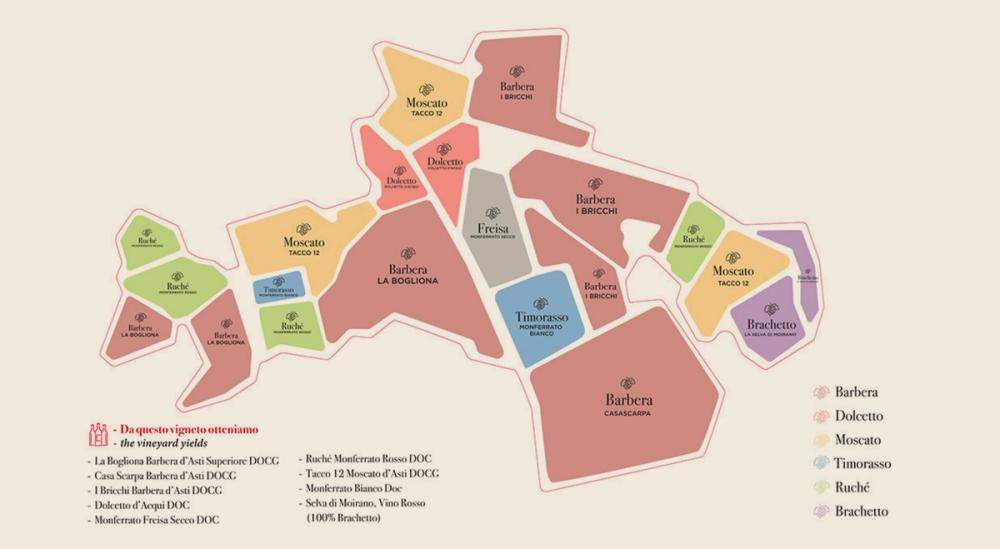

It was also reassuring considering how far Scarpa has invested in planting and really getting to understand what each of the native varieties it is growing in Monferrato in Piedmont. A line up of native grapes that includes:

- Barbera

- Nebbiolo

- Dolcetto

- Moscato

- Ruche

- Timorasso

- Pelaverga

- Freisa

- Brachetto

“That’s what we produce and that’s what we are,” said Champion.

He said it almost felt like an “obligation” for it to be so committed to indigenous varieties as it was part of its heritage, its history, as a traditional Piedmont producer. Even though it can be be more expensive in terms of how the vines are managed and then vinified and then stored separately in the cellar, he added.

Its history

A breakdown of the local indigenous grapes grown by Scarpa

Scarpa’s roots in Piedmont date back to 1900 when it was founded by Antonio Scarpa. In the 123 years that has followed there have only been four people in charge of winemaking at the estate, from Antonio Scarpa through to current winemaker, Silvio Trinchero who joined in 2007.

Trinchero told the panel how he is pleased, and honoured, to be able to carry on the traditional winemaking practices that make Piedmont and, hopefully, Scarpa wines so special. “It is the best philosophy. It is important to me to preserve these varietals and their small production.”

The key, he said, was to not to produce too many grapes but ensure there was the “right balance” in the vineyards for what they need to make the best quality wines.

Its first Barolo was produced in 1940 and Langhe which is why it is still allowed to make Barolo outside of the usual denomination.

It has grown to a 45-hectare estate, located between Monferrato and Langhe, of which 30 hectares are under vine. All between 250m to 400m in altitude. The majority of vines (25 hectares) are at Poderi Bricchi, Scarpa’s most historic vineyard dating back to 1969, which sits on the border between the hills of Asti and Acquit Terme. Here it grows the majority of its indigenous varieties Barbera, Ruchè, Brachetto, Dolcetto, Freisa, Moscato and Timorasso.

The Monvigliero vineyard acquired in 2018 has given Scarpa access to high end Nebbiolo grapes for its Barolo and Barbescos

Among its most recent vineyard acquisitions have been focused on cementing its position as a premium Langhe producer with vines bought in 2018 at Monvigliero (two hectares) in Verduno and Canova (2 hectares) in Neive both producing Nebbiolo ideal for single vineyard Barolo and Barberesco.

Champion describes the introduction of these vineyards into Scarpa as marking a “new chapter” for the business “in terms of our vision for the next few years”.

It also has Roncaglie, a 1.2-hectare plot of Nebbiolo, that sits on the border between Verduno and La Morra, one of the most renowned towns on the hills of Barolo.

Up to 65% of its wine goes to export and it is producing around 150,000 bottles a year.

Patience is the key to producing quality wine at Scrapa. “We know how to wait,” is how Champion puts it. The key, added Trinchero, is to only release wines when they can be drunk straight away. Which can be frustrating as a a winemaker when you are so keen “to see the results”.

Champion says they are pleased when you can see a distinct “Scarpa style” in the wines that reflect its heritage and traditions and its winemaking style of typically short macerations and long maturation and ageing.

Buyers’ Tasting

Piedmont’s rare indigenous varieties through time

Scarpa winemaker Silvio Trinchero was able to take the buyers through Scarpa’s different styles of wine make from its historical indigenous grape varieties

To help give the buyers and importers a chance to see how Piedmont’s rare indigenous varieties change over time they were able to take part in a tasting – split into three flights – that showed wines but from different vintages stretching from 1996 to 2019.

“We are proud of how our wines can age so we wanted to show you wines over 20 years,” said Champion. “We share our heritage, and we share our obligation with you.”

Champion was keen to stress that many of the wines in the tasting were not being released into the market on a commercial basis but were being shown to the buyers to demonstrate what it can do and what is available.

Champion and Trinchero were also able to explain how each indigenous variety is picked, vinified and aged separately so that it can focus in on the potential and performance of single vineyards.

The ultimate goal is to make wines that are elegant “and with finesse” and that “are a clear expression of the varietal,” said Champion. “That is the aim of our vinification and our philosophy,” he said.

1st Flight

The first flight of wines looked at the Dolcetto and Freisa grape varieties

Dolcetto D’Acqui DOC 2018

Dolectto D’Acqui DOC 1998

Freisa Secco Monferrato DOC 2019

Freisa Secco Monferrato DOC 2013

The first flight was a chance to look at two traditional Piedmonte varieties: Dolcetto and Friesa.

Dolcetto

Piedmont has several separate denominations for Dolcetto and here we were able to look at what is produced in the small area of D’Acqui that makes a more “structured” style of Dolcetto, said Trinchero.

Scarpa follows traditional vinification for its Dolectto wines, added Trinchero, with up to 13 days of maceration, with only two pump overs per day and then 18 to 20 months ageing in stainless steel tanks before minimum ageing of six months in bottle.

Parker said Dolcetto is certainly one of the more recognisable grape varieties from the region and “more consumer friendly” in terms of style at a younger age. “If you had an indigenous shortlist, that would be one of the ones.”

Johnson said there is certainly an interest in Dolcetto, albeit on a small scale, and it does not sell, for example, as much as Nebbiolos from Langhe, “but there is still a demand for Dolcetto”.

De Luca welcomed the opportunity to be able to taste a 1998 Dolcetto and was “pleasantly surprised” by its quality. “It was extremely good.”

Freisa

Scarpa’s Davide Champion says the producer was keen to better understand what UK buyers are looking for and where indigenous varieties sit in terms of their buying needs

Freisa is one of the most rustic varieties in Piedmont and its DNA analysis is very close to Nebbiolo, claimed Trincheero. The big difference being Freisa’s rustic tannins which makes it hard to drink the wines young. The two wines chosen to taste also illustrate the impact of climate change in Piedmont with the 2019 picked on October 8, compared to October 25 for the 2013 vintage.

“We now have to work less, but better in the vineyards due to climate change,” he added. Picking the fight time to pick is even more important in order to keep the acidity and freshness in the grapes.

Freisa is certainly a grape variety more suited to a hands sell by sommeliers “looking for a bit more colour on their lists,” said Johnson. “By the glass is where you might get some volume.”

“There is no pull [for Freisa],” said Palmer. “You would have to push really hard especially when you have Nebbiolo and Barbera. It’s a flooded market. This is super niche and a tough sell,” she added and perhaps better suited to selling and promoting as part of Scarpa’s hospitality at the winery where visitors can really explore what it is about.

That said there is “always somebody to whom you can sell a wine like this,” she added.

Briccarello said he loved the “ageing potential” for Freisa and could see a few of his customers taking it on.The ageing certainly works well on the 2013 Freisa, agreed Parker, with softer, more approachable tannins.

2ndFlight

The second flight focused on Scarpa’s Barolos and Barberas over two vintages

La BoglionaBarbera d’Asti DOCG Superiore 2017

La Bogliona Barbera d’Asti DOCG Superiore 1996

Tettimorra Barolo DOCG 2019

Monvigliero Barolo DOCG 2018

This was an opportunity for Scarpa to show its “new chapter” of Barolo that is being made from different single vineyards, enhanced by the purchase in 2018 of the Monvigliero (two hectares).

The buyers had the chance to taste the first two Barolo wines made from the newly acquired vineyards: the Tettimorra Barolo DOCG 2019; and Monvigliero Barolo DOCG 2018.

Wines that arguably best illustrate Scarpa’s philosophy of short macerations (minimum weeks) and then long ageing in large wooden barrels for 30 to 36 months. A slow maturation helps make a quality, balanced wine, said Trinchero. The wines are then bottled and aged for a minimum further year.

He describes Monvigliero as one of Scarpa’s “most important vineyard” with its rich complex of clay soils that includes a lot of magnesium that helps in the balance of the overall wine.

The Barbera wines also show, he said, how resistant the grape has been to climate change and is actually making wines now with more structure, whilst retaining acidity and freshness “which is extremely important for the ageing of the wine”.

Darlington was particularly impressed by the La Bogliona Barbera d’Asti DOCG Superiore 1996 and how it has retained the “fresh, lively and juicy” characteristics that you associate with a young Barbera. “This has retained that. It’s staid fresh and vibrant whilst being able to evolve. It’s very impressive.”

Palmer agreed: “I agree. It has so much life. It has aged beautifully but I prefer the 2017, for me that is more like Barbera.”

Johnson said it was always interesting to have the chance to taste such aged wines and was impressed by how much the acidity in the 1996 Barbera had been “kept alive” even if it was now borderline volatile acidity.

Darlington says it is good to see wines with a bit of age – and compared to what is the market even a 2017 wine is now seemed to be quite old

Darlington said the fact the 1996 Barbera is so old “obscures the fact the 2017 is also quite old” in terms of the Barbera d’Astis in the market that are usually only two to three years old.

But for Scarpa having such a relatively old wine as its current vintage, at least from its La Bogliona label, is quite normal, said Champion.

“The 2017 is drinking extremely well now,” said Cremonese.

Barolo and Barbera opportunities

The panel said there was a fresh opportunity for Barolo in the UK market on the back of the fallout from hugely increased Burgundy prices. Which means, argued Palmer, in particular, that “Barolo looks incredibly good value by comparison”.

Darlington said it was seeing that for itself at the new wine store it has opened up close to Sloane Square in London, where it assumed there would be big demand for the French classics and stocked up on high end Bordeaux and Burgundy. Only to find “all the unprompted demand is actually for Chianti Classico, Brunello, Barolo, Barbaresco – it’s high-end Italian,” he said. “It’s shocked us, it has really taken us by surprise.”

Scarpa’s winemaker Silvio Trinchero was keen to show buyers ‘pairs’ of indigenous varieties in different flights to illustrate the diversity of styles

Similarly the demand to pay for tastings is easier to sell out for events focused on say Barolo, or Brunello, but far harder for French classics like Burgundy. “The customer is leaning towards a style as well as a price. Italy offers that style.”

He also thinks restaurant wine lists, particularly premium gastro pubs, are leaning more to having a high-end Italian, like Barolo, as their highest price as it is “just a bit classier” than having “Chateau something on your list”.

De Luca hoped this new interest in high end Italian wines was not just because they offered better value, but because of the quality of the wines on their own.

Darlington said the evidence from its store certainly backed that up. “What we are seeing from our shop in Chelsea is that people just want Italian and will spend £100 on a bottle of Barolo as it offers such good value for money.”

Cremonese argued the popularity and prevalence of quality premium Italian wines versus their French equivalents is also opening people’s eyes to what Italy can offer at the top end.

3rd Flight

The third flight was a big success with the buyers and a chance to taste Rouchet and Brochetto wines

Rouchet Monferrato DOC Rosso 2019

Rouchet Monferrato DOC Rosso 2009

Selva di Moirano Brachetto 2019

Selva di Moirano Brachetto 2007

The third flight focused on the aromatic and semi aromatic varieties that Scarpa is using – Rouchet and Brachetto. It originally used to buy in Rouchet grapes before planting its own vines in Poderi Bricchi.

Both its Rouchet and Brachetto wines are vinified and aged in stainless steel tanks.

Trinchero said one of the key characteristics of Brachetto variety is how it loses it flowery notes and develops more pepper and spice the more it is aged.

“It is very interesting to see the evolution of this wine,” he said.

Scarpa is one of the few producers still making Brachetto wines and although its production is small – only 2,000 bottles – it has built up a strong following.

The Rouchet wines stood out for the buyers on the panel

The panel could see why. Briccarello thought the two Brachetto wines “were amazing” and particularly liked the ageing and spice in the 2007 which was “almost like a vermouth” and the freshness of the 2019. “It would be interesting to see how these could work on a menu.”

Trinchero said it is hard to find old vintages of Rouchet and Brachetto and they are good wines to offer chefs looking to pair wines with more unusual dishes.

That’s where indigenous varieties really have role to play, argued Darlington. “It’s where something can offer a genuinely different style, that’s when you start to see opportunities.”

There are, after all, he argued, a lot of very local Italian varieties that you “can put in the same box – they’ve got big tannins, they’re quite dark, they taste of cherries, they taste Italian.” But if you can step outside that and offer something totally different – that’s where the potential is, he claimed.

“That’s why something like this is quite exiting, and you can see why sommeliers would get excited as you can pair it with food and can see gaps onwine lists as the style is different.”

In summary

Jascot’s Briccarello said it was an “amazing” opportunity to be able to taste this wide selection of historical Italian indigenous varieties in one tasting

The panel had mixed views on which of the indigenous varieties they tasted had the best chance in the UK.

Of the lesser-known varieties Johnson said he would pick out Freisa, Brachetta and Rouchet as being the three with the most potential.

“I would go for Brachetta because of the style,” said Darlington.

Parker said if you were looking to “pick something completely different to what you have had before” then she would go for Rouchet.

Briccarello said it was an “amazing” experience to be able to taste all these indigenous varieties in one go and, in particular, try the aged wines, most noticeably from Freisa and Brachetta. “It is impressive to see how these wines evolved and the patient work they do storing all these wines.”

In terms of standout wines he would go for the Freisa 2013 and the Brachettas.

Sergio du Luca said he was taken a back bay the Brachetto wines and they were not what he was expecting

De Luca said he was also taken a back by the Brachetta wines and were a bit of a “discovery” for him as he usually associates them from the sweeter style that is produced. “Those wines were fantastic.”

But he was particularly taken with the “very drinkable and very good’ La Bogliona Barbera d’Asti DOCG Superiore 2017 as it captured the classic style, but also had a lot of spice and vibrancy.

Palmer also liked “the lovely example” of La Bogliona and “was very gratifying” to be able to taste a 2017.

“In terms of the surprise factor it is the Brachetta and Rouchet,” she added, particularly as they are not “too tannic, or too demanding” and therefore have “more opportunities with a wider and potentially younger audience”.

But when it comes to “getting a market for something completely different it would be Flight 1 where I would punt”.

- You can find out more about Scarpa and the wines it is making at its website here.

- Our thanks go to the team at Vinoteca in the City for hosting and looking after us.